On-Trade-Off: Countering Extractivism by Transnational Artists’ Collaborations

The term extractivism signifies far more than the literal extraction of raw materials from soils: it speaks, in a broader sense, to the structural foundations of global capitalism, its colonial history, and its ongoing afterlives comprising contemporary ecocides. It refers to an “understanding that the world, and all its beings, are inherently commodifiable, violently turned into ‘things’, operating as a standing reserve for the accumulation of profit and power in the hands of a few.”1

Global capitalism is fuelled by fossil energies, which are most often extracted for the benefit of transnational companies collaborating with national governments, but to the detriment of local populations. In the past decades, extractivism has been theorized mainly in South American scholarship highlighting the “dramatic material change to social and ecological life that underpins [racial capitalism]”.2

In an extended viewpoint, the critical discussion of power structures in the global art world refers to extractivism to describe the frequent incorporation of artists from the Global South into galleries, biennales, fairs and exhibitions located mostly in the urban centres of the North, often without long- term engagement for the sustainable working structures in their countries of origin. While the symbolic surplus of the artists’ practice is appropriated unilaterally, the power of the metropolitan centres remains largely untouched.

How can an artist collective address the profit-maximizing structures of extractivism? A collaboration between a dozen artists and writers on three continents, On-Trade-Off enters the ‘extractive zone’, critically examines its functioning, and searches for alternatives. Several artists and thinkers gravitating around the initiatives Enough Room for Space (co-founded by Marjolijn Dijkman and Maarten Vanden Eynde, Brussels, 2005) and Picha (co-founded by Sammy Baloji and Patrick Mudekereza, Lubumbashi, 2009) pushed their long-term conversations further and started to collaboratively inquire about lithium mining in the Congo, the pitfalls of the promises of the green energy revolution, and more broadly, the unequal distribution of risks, destruction, wealth and opportunities along global value chains. The group’s configuration are evolving and dependant on the specific focus chosen for an exhibition or an event.3 It is nevertheless of crucial structural importance that the project relies on a collaboration between a collective in Lubumbashi, in central Africa, and another in Brussels, at the centre of Europe, with members joining from changing geographical locations, including Australia, requiring constantly to take into account the realities experienced on all sides.

The geographical starting point for the project is a site of extractivism par excellence: the Manono mine, situated in the Tanganyika province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 500 kilometers from Lubumbashi. While the mine has been exploited for its tin reserves since 1919, it recently became the focus of international speculation on strategic raw material for the green revolution: as explorative drillings conducted by the Australian company AVZ in 2018 have shown, the soil contains high concentrations of lithium, an alkali metal with high capacities to store electricity. The prospecting on the mine’s ores that also contain cassiterite and coltan, both metals of strategic importance for wireless communication, constitutes a conundrum that On-Trade-Off examines: while promising to provide a more sustainable technology, the future extraction of the ore will most prob- ably reproduce the exclusion of local populations from the wealth of their soils.

A collaborative project between two artist collectives in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Belgium renders today’s asymmetrical structures of the world-economy and their colonial history a palpable reality on many levels. While being connected through the value chains of global industries, artists participating in the On-Trade-Off project do not experience the same realities, due to their geographical situation. They work with different tools, undergo heteroge- nous journeys, and adhere to diverse aesthetic approaches. The frequently abstract terminology that conceptualises extractivism materializes in the artworks as concrete takes on the world, engaging with the local aftermath of globally traded ores, and their transformation into consumer products.4 It is precisely this interconnected reality that the transnational artistic research project On-Trade-Off critically interrogates.

In this text we will stress that On-Trade-Off strives, by its very structure, its multi-sited geography, its collaborative intention, and the internal redistribution of resources, to resist the rampant extractivist logics of the global art field, including the neo-exotic tokenism of artists from the Global South. By developing On-Trade-Off as a permanent dialogue between artists living and working closely connected to the sites of extractive mining, and group members confronted in their direct environment rather to the seducing surfaces of the electronic end products, the project systematically connects the extremities of the world spanning value chains that oftentimes are dissociated.

Installatiefoto van de tentoonstelling Charging Myths (2023) bij Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

Ambiguous Crossroads

How to work with the vocabulary of the neoliberal economy? On-Trade-Off advances in a field dominated by powerful corporate interests and the language of financial speculation. The collective’s work is permanently obligated to deal with forces that exceed its own possible impact. Reformulating Audre Lorde’s fundamental question, it must ask incessantly if the available conceptual and aesthetic tools can contribute to dismantle the extractivist house.

As a consequence, the group engages in continuous criticism and selfreflection, not only in the visual production, but also at a linguistic level: in neoclassical economic theory, a trade-off designates situations where increasing one part of an equation requires diminishing another.

Transnational Collaborations and Technology

On-Trade-Off develops through evolving iterations and context-specific exchanges, taking part in a growing network of activists, researchers, and fellow artists. It considers that the plurality of experiences allows for a more precise understanding of the global realities of extractivism. The photographic work of Georges Senga (DRC/NL, 1983) is for example closely tied to the mining history of Lubumpichbashi, testifying of the decisive impact of the mining giant Gécamines for generations of the cities’ inhabitants.

The artists Edmond Musasa (DRC, 1950) and Maarten Vanden Eynde (BE, 1977) work together on a series of tableaux representing the chemical elements, playfully quoting chalkboards and school charts and their educational usages (Material Matters, 2018-ongoing). Their approach breaks with the division of applied art and high art, brings together two artists of different generations and living situations, and explores how a collaborative learning and transmission process can look like.

But approaches can also remain distinct and still create strong resonances allowing for all parts to reach new dimensions. Such is the case for Jean Katambayi Mukendi’s (DRC, 1974) hand-made speculative drawings and machine-sculptures, and the slickly designed multi-media installations of Femke Herregraven (NL, 1982), that often draw on financial data sets and the visualisation of speculation. Katambayi’s work challenges the detrimental effects of mining on local populations by imagining how to appro- priate the technological potential of the industrial tools, and to feed it into future design and urbanism. The research of Herregraven examines the abstract finan- cial renderings of the world, which she interrogates critically as a means of domination, but also explores as a source of imagination.

Digital Working Tools and Their Global Entanglement

None of the complex structural questions interrogated by On-Trade-Off are external to the group itself. It is a transnational collective based on three continents that is strongly dependent on the very technologies scrutinized by the groups’ research: the Covid-19 crisis with its worldwide impact presented a particularly paradoxal situation for the work of the highly mobile artists group. During the lockdown, members have been based in Lubumbashi, Sydney, Brussels, Paris, Amsterdam, and Zagreb. The transnational collaboration remained generally possible via computer and smart-phone screens, revealing the striking differences in quality, cost and accessibility of the internet connection, and more broadly electricity in each location. Even if the massive extension of internet-based communication led to decreasing international air-travel with its destructive ecological footprint, it nevertheless remains dependent on raw material consuming technologies, and their ongoing supply: we know about the energy consumption, water usage, toxicity, and waste caused by the production and use of digital media, that belie corporate myths of their immateriality.5 On-Trade-Off’s research depends heavily on electronic media, and thus takes part in an economy that extracts labour from bodies; minerals, gas, and oil from the ground, and that has no inherent limits to the permanent accumulation process.

Still, the ongoing research demonstrates that transnational collaboration can contribute to counterbalancing the structural exploitation. Efficient technologies, presented as the solutions of the ecological crisis in the North; the concentration of extraction and outsourcing of hazardous waste in the South, and anti-migration laws, and increasing social exclusion go hand in hand.

Australian based artist, Alexis Destoop (BE/AU, 1971) is working on a film on the history and becoming of lithium, reaching from cosmological tales of origin to its role as a supercharger in energetic cycles, and (re)tracing the journey of the transformation of this volatile element. From the vantage point of the Asia-Pacific, he sees the geopolitical struggle over the control of strategic resources intensifying. Destoop’s research engages with the blind spot of his life in between Australia and Belgium, and their particular colonial histories, and strives for narrative and visual elements allowing to navigate a horizon obstructed by dystopia.

Pélagie Gbaguidi’s (BJ/BE, 1965) work addresses the existential urgencies generated by techno-capitalist exploitation and connects its local realities to global entanglements. During a residency in 2019, she travelled from Brussels to Lubumbashi, where she worked with women labouring in an informal mine close to the nearby town Kipushi, where cobalt, another central ingredient for the production of lithium batteries, is extracted in health-threatening conditions.

Unravelling Speculation

The group evolves between analytical criticism of extractivism in the artworks, and its own implication in the asymmetries of the global economy, without ever claiming to remain unaffected by the powerful structures that it interrogates. Marjolijn Dijkman (NL/BE, 1978) dives into the history of electricity, its pre-scientific staging as a spectacle, and the constitution of scientific electrical knowledge in the 18th century. Dijkman’s research highlights the parallels drawn by Benjamin Franklin, author of core elements of today’s electricity storage. For Franklin, the control over power promised to master nature, and to counterbalance poverty by wealth. Dijkman questions his faith in progress, and connects it to the promises of today’s green revolution.

Making and Crashing Together

Today, the rhetoric of sustainability and global responsibility is common in the communication of global companies. Tesla Inc. for instance announces to accelerate the “world’s transition to sustainable energy” by selling high-end electric cars, designed to move with regenerative energy, stored in lithium batteries. For its batteries, Tesla Inc. requires huge supplies of lithium – and may thus be one of the clients of the prospective mining of the ore in the city of Manono.

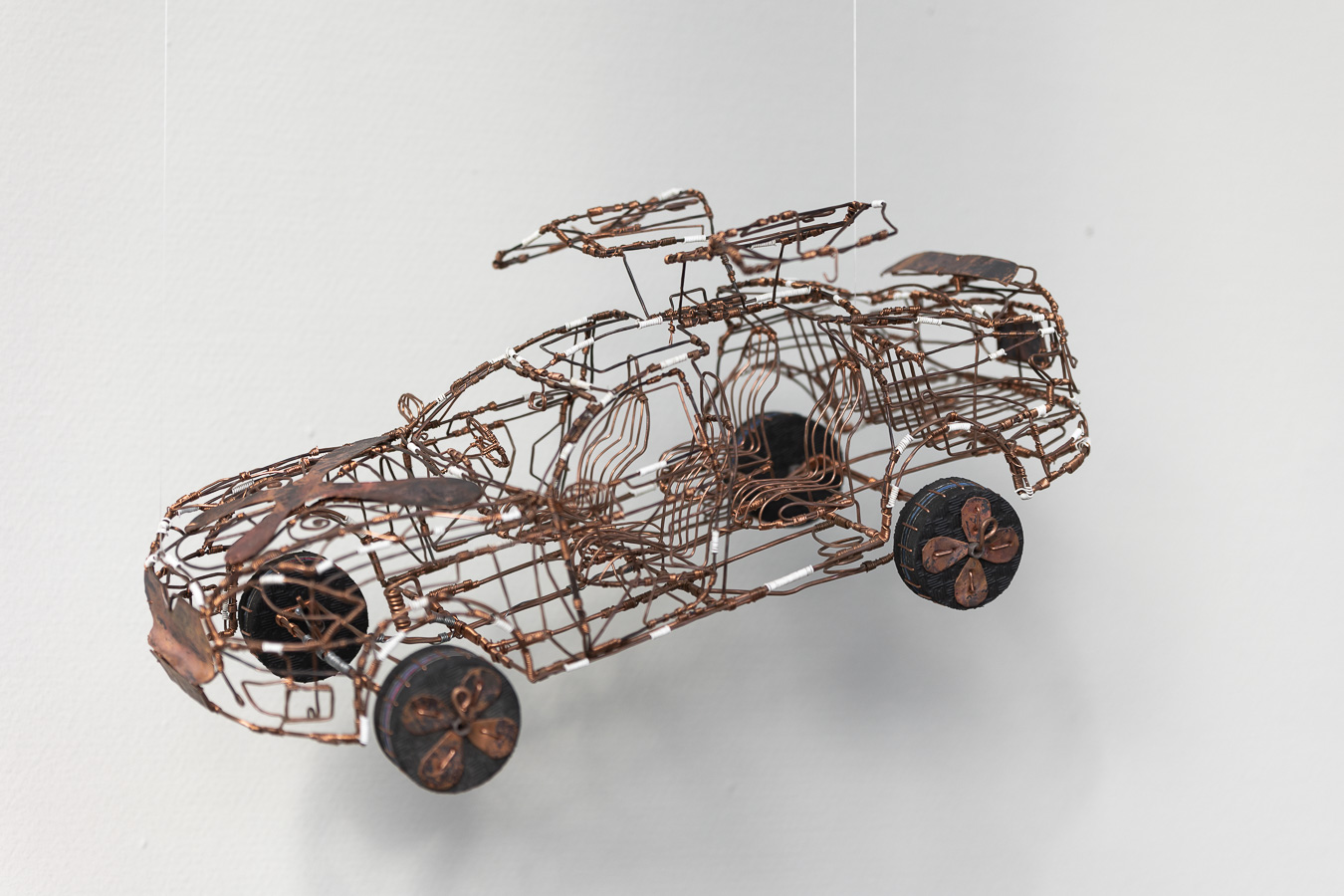

In the present distribution of power, it is likely that “the promise of the green car of the future is valid only for the part of the world that will enjoy its use, [while] the environmental impact is displaced in the areas of extraction and refining of materials that compose it.”6 Challenging this situation, the artists Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Sammy Baloji (DRC/ BE, 1978) and Daddy Tshikaya (DRC, 1986) conceived and constructed, in their hometown Lubumbashi, a realsize Tesla car using copper wire: Tesla Crash: A Speculation. The remarkable object is an outcome of collective intelligence and collaboration, using copper, a raw material that is pres- ent in high quantities in the soils of the Katanga region, and has been mined extensively since pre-colonial times. The copper-wire Tesla car has been skilfully constructed over several months at Picha in Lubumbashi (2018-2019), gathering numerous concerned and interested audiences around the daily construction process, or in workshops dealing with energy and technologies for the future.

Far more than an object, the car is still generating collaborations. During the Lubumbashi Biennale in 2019, artist Dorine Mokha (DRC, 1989 – † 2021) weaved his perfor- mance around it, entering call-and-response with the audience, and initiating future collaborations with the On-Trade-Off project. In close conversation with the three conceivers of the wire car, Marjolijn Dijkman prepared the performance Charging Tesla Crash: A Speculation. Jean Katambayi led through the ceremony, while Dijkman discharged from a home crafted electric Tesla coil 3 million volts over a distance of 2 meters on the highly conductive copper car

At the modest scale of an artist collective, On-Trade-Off strives to counter extractivist structures and to collaboratively speculate on possible scenarios for alternative manners to live together on an interdependent planet, to open ideas beyond the protective localism of wealthy ecological policies, and the structural racism of global technocapitalism. Examining future modes of travel and transnational collaboration, and the continuous self- reflecting on the group’s structure and its inherent biases, are among the challenges for the coming months and years. While it cannot pretend to mitigate the destructive power of capital, it “stays with the trouble” (Haraway 2016) and engages enthusiastically in collaboration as a source of learning in multiple perspectives, and mutual transformation.

By Lotte Arndt and Oulimata Gueye

Februari 2023

1. Heather Davis, “Blue Bling. On Extractivism”, Afterall, no. 48, Autumn 2019. https://www.afterall.org/journal/issue.48/blue-bling-on-extractivism

2. Macarena Gömez-Barris, The Extractive Zone. Social Ecologies and Decolonial Perspectives, Duke, 2017, p. xvii.

3. At different moments, the group involved so far the artists Sammy Baloji, Alexis Destoop, Marjolijn Dijkman, Pélagie Gbaguidi, Femke Herregraven, Jean Katambayi Mukendi, Dorine Mokha, Musasa, Alain Senga, Georges Senga, Daddy Tshikaya, Pamela Tulizo, Maarten Vanden Eynde, and the writers and curators Lotte Arndt, Oulimata Gueye and Rosa Spaliviero.

4. Chéneau-Loquay Annie, “Mobile Telephony in African Cities. A successful adaptation to local context”, L’Espace géographique, 2012/1 (Vol. 41), p. 82-92. https://www.cairn-int.info/journal-espace-geographique-2012-1.htm

5. Laura U. Marks: “Let’s Deal with the Carbon Footprint of Streaming Media”, Afterimage, 2020, 47 (2), p. 47. https:/doi.org/10.1525/ aft.2020.472009

For a critic of the rhetorics of dematerialized communication see: Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski (eds.), Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, Champlain, Illinois, Universi- ty of Illinois Press, 2015.

6. Oulimata Gueye, “No Congo, No Technologies”, Digital Earth, 2019. https://medium.com/ digital-earth/no-congo-no- technologies-163ea2caec0a

Extractivisme / Ecologie /

Exposities

Expositie: Charging Myths

Een tentoonstelling van het transnationale collectief On-Trade-Off waarin wordt onderzocht hoe technologische innovatie afhankelijk is van natuurlijke hulpbronnen.

Netwerk

Lotte Arndt

Onderzoeker, Auteur, Curator

Alexis Destoop

Kunstenaar

Marjolijn Dijkman

Kunstenaar

Pélagie Gbaguidi

Kunstenaar

Femke Herregraven

Kunstenaar

Jean Katambayi Mukendi

Kunstenaar

Edmond Musasa Leu N’seya

Kunstenaar

Georges Senga

Kunstenaar

Maarten Vanden Eynde

Kunstenaar

Oulimata Gueye