Report: How to Un/Engender the Ethnographic Object?

On 24th June 2017, the symposium Declassified: How to Un/Engender the Ethnographic Object? took place at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam. In collaboration with Framer Framed, the Research Center for Material Culture (RCMC)—the flagship research institute at the heart of the Tropenmuseum (Amsterdam), Museum Volkenkunde (Leiden), and the Afrika Museum (Berg en Dal)—developed the program; the first in the larger Un/Engendered series of lectures and events, in which scholars, activists, and artists are invited to question and rethink the relationship between gender, sexuality, and patriarchy in contemporary societies. The principal goal of this first event was to “trace the (historical) construction of gender and sexuality within the collecting practices of ethnographic museums” , and from there to discuss how it may (or may not) be possible to successfully ‘un/engender’ ethnographic objects and collections in the future.

Accordingly, the problematic nature of normative and restrictive European conceptions of gender and sexuality, which have been entangled in ethnographic collections and collecting policies since the very first ethnographic museums opened their doors, provided the crux of the afternoon. The five speakers at the symposium traced and explored this institutional issue, particularly in terms of the questionable interpretations, classifications, and representations of ethnographic objects that have resulted from it, while remaining focused on one central question: “What does it mean for a museum to side-step its own body of knowledge and critically rethink its own understanding of how gender and sexuality are attached to its objects?”

Director of the RCMC, Wayne Modest, opened the three-hour symposium with a general introduction and explanation of the overarching aims of the event. He situated the symposium within the current global trend of criticising the role, purpose, and future of museum practice—particularly those museums that maintain powerful connections to imperial and colonial histories. Setting an explicitly critical tone for the presentations which were to follow, he described the ethnographic museum as a distinctly male space, evident not only in the visible over-representation of men and masculinity in many ethnographic collections (this is particularly apparent in photographs, he said, which often depict men, war, trophies, and violence) but also in collection trajectories and methodologies, both past and present, which frequently organise objects around the dominant social logic that there is an inherent, clearly defined, ‘maleness’ and ‘femaleness’.

It is this binary logic, Modest went on to explain, that the symposium sought to disturb, question, and rethink; providing the space for discussions about what it might mean to look at ethnographic collections differently, through new lenses of gender and sexuality, or even through a feminist gaze. Importantly, he emphasised the tentative nature of this, expressing that the programme would involve thinking critically and creatively into the future, and therefore would be “provocative” and “experimental”, to use his own words.

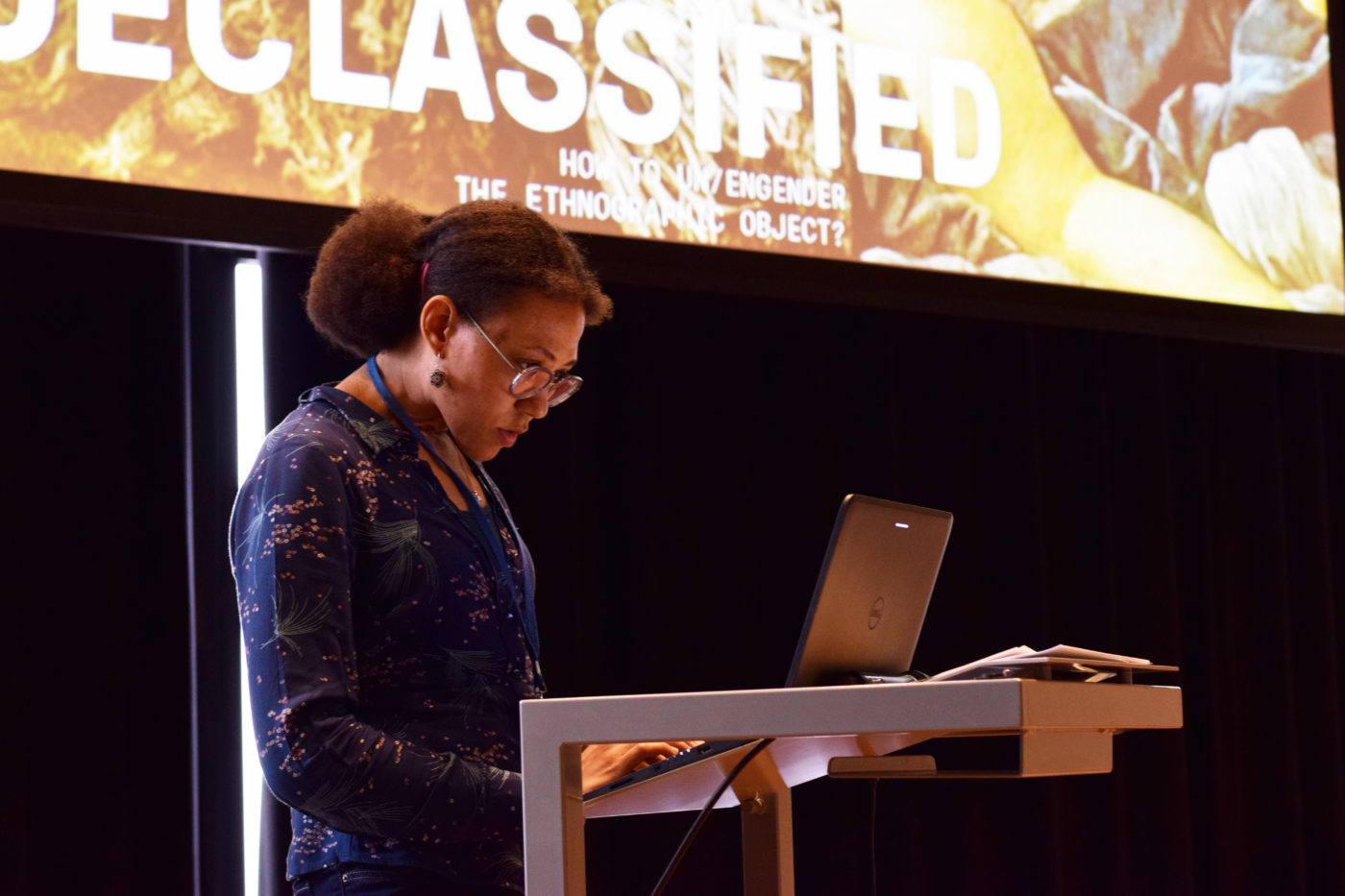

Following this short introduction, Dr. Wonu Veys, curator at the National Museum of World Cultures, took to the stage. Her presentation was titled Capturing the ‘female essence’, and the object of analysis was ‘barkcloth’, a cloth made from inner tree bark in The Kingdom of Tonga among many other places. Veys explained to the audience that barkcloth is often spoken of belonging to a group of objects named ‘koloa’, which are considered specifically ‘female’ objects by anthropologists. This is because for centuries it has been only Tongan women who have engaged with it. Still today women take pride in making and wearing it, as well as presenting it at ceremonial exchanges. Barkcloth (as a koloa object) is therefore, she went on to clarify, often considered the materialisation of female skill and effort, leading to the belief among scholars “that the value of koloa corresponds to the value of women” (Quote from the speaker).

After establishing why barkcloth is viewed as a gendered object and why it is valued, Veys moved on to acknowledge the criticisms of seeing objects as gendered, classifying and categorising them into complementary oppositions of ‘male’ and ‘female’. She argued that this is an exceedingly simplistic duality in which to place objects that connect to hugely complex cultures. She also mentioned that classifying objects through gender categories results in a seemingly natural ‘division of labour’ and thereby to fixed conceptions of what it means to be a woman. Her conclusion was that we in the West should refrain from calling koloa objects (such as barkcloth) ‘female’, and instead call them ‘prestigious’, because of their prestige in the local context and role in bringing the community together in ceremony. Some important broader questions were raised in my own mind after hearing this: Should we continue to see ethnographic objects as so strongly gendered? Should we really view goods and objects as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’; textiles and ‘soft’ objects as a woman’s domain, and harder objects (weaponry, clubs, and swords) as male objects and the territory of male collectors? By doing this, do we not simply reinforce normative and fixed notions of gender and sexuality?

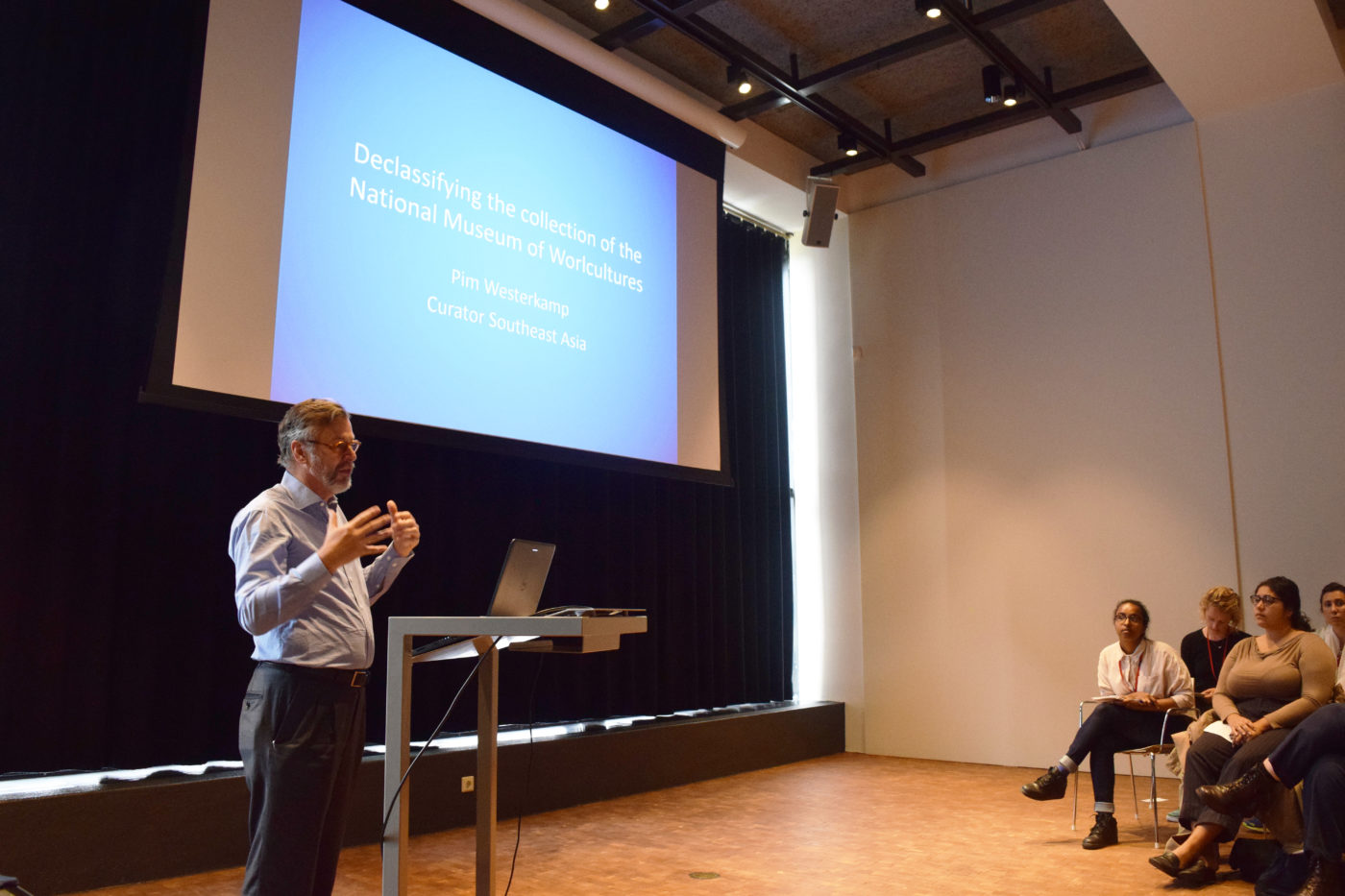

The second presentation, Declassifying The Collection of The National Museum of World Cultures, was given by another curator at the National Museum of World Cultures, Pim Westerkamp. Here the discussion moved away from physical ethnographic objects and towards images, particularly portrait photography. Westerkamp began by presenting a selection of art and photography by gay artists, which he claimed raise urgent questions about the ways in which we might view images such as these. Regarding a landscape painting by Walter Spies, the German painter who spent much of his working life in Indonesia, Westerkamp asked, “Does the landscape have a gender?” In connection to photographs taken in Algeria by the Dutch artist Rudolf Bonnet, he posed the question “Is this work gay because he [the photographer] is gay?”

His main point here seemed to be that the way we view the work of LGBTQ artists depends on our own perspectives and cultural norms, in his own words, it is “all in the eye of the beholder”. Westerkamp then moved on to question how ethnographic museums should present and display these images, especially those that appear to represent some form of fascination with the indigenous body. This led to his conclusion, that in the future, ethnographic institutions should attempt to look differently at these historic images, which involves investigating whether Western notions of homosexuality can, and should, be applied to other local cultural contexts, the point being that perhaps homoeroticism in the colonial past should not be judged by contemporary Eurocentric standards and norms of gender and sexuality. The title at the top of one of his presentation slides summed this up well: “Camp, seduction, or norm?”

Next, a recorded lecture by artist Maria Guggenbichler was played, which marked a break in looking at specific cultural objects and imagery. The artist was present in the audience, but explained that she preferred to give her lecture from the private setting of her own home, from a place that she feels comfortable in. Guggenbichler argued that if we want to talk about gender in the context of the museum, we cannot only talk about the gender of objects, rather we must talk about the institutionalisation of gender and sexuality. Similar to Wayne Modest, she spoke explicitly of the ethnographic museum as an institution of patriarchal heteronormativity, and of the ethnographic collection as “proof of the non-humanness of the other” (in her own words). Based on the arguments of the Critical Race Theorist Maria Fernandez, she stated that both race and gender should be thought of as oppressive technologies of colonial warfare that sought (and still seek) to divide and rule; to separate people in order to dominate them and enforce patriarchal rule. By explaining both race and gender within the same concept of a ‘technology’, she linked the two; suggesting that to decolonise the ethnographic museum concerns not only tackling race but just as importantly, negotiating themes of gender and sexuality.

She went on to indicate that ethnographic museums must analyse how heteronormativity has been exported and enforced upon the Other as a method of enforcing white colonial power. Furthermore, she argued that that in order to subvert the logic of these institutions, we must first understand and analyse this logic—in other words: only knowledge of the system will enable us to think outside of it. “Queering the ethnographic collection”, in Guggenbichler’s opinion, therefore demands that ethnographic museums must let go of their claims to “authority, objectivity, neutrality, and universality” (quote from the speaker), and begin to acknowledge that the ethnographic collection is at it’s core a collection of queer people and of queerness, as a result of the fact that every object and objectified person (the Other) connected to the collection did not fit into the categories constructed by the white supremacist patriarchy of their time. This, she stated, is the story ethnographic museums should tell. At this point, oceanic sounds, the whispers of crashing waves—assumedly a metaphor for the maritime colonial contact so crucial to the ethnographic encounter—took over. A voice spoke above the waves: “How to unthink something you don’t know you’re thinking”.

Artist and RCMC fellow Shigeyuki Kihara was the final presenter of the day. Her interdisciplinary work engages in variety of social, political, and cultural issues. Often referencing Pacific history, her work explores the varying relationships between gender, race, culture and politics. Kihara has been exhibiting internationally since 2004. Shigeyuki Kihara was a participating artist in the Framer Framed group exhibition Embodied Spaces (2015), curated by Christine Eyene.

Public event during the exhibition Embodied Spaces (2015) – Photo (c) Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed

Shigeyuki Kihara began by introducing herself as a dual citizen of Samoa and New Zealand, as well as her identity and experiences as ‘fa’afafine’, which translates into English as “in the manner of a woman” and is applied in the Samoan context to those who are biologically male but identify as female. Complementing Guggenbichler’s presentation of heteronormativity as a colonial technology and export, she then moved on to briefly discuss Samoan colonial history by describing how streams of colonisers and missionaries came to the Pacific islands and enforced Western gender categories and identities upon Samoans. The romanticised and eroticised portrait photography produced by cisgendered white ethnographers who came to Samoa was the inspiration for Kihara’s 2005 body of work. The models of these portraits were unnamed, leaving her with the feeling that they were objectified. She explained that this formed the basis of her series, in which she used her own body as an artistic material to re-enact colonial photographs, performing different gender identities in order to comment on the politics of gender in Samoa.

The end of Yuki Kihara’s presentation was followed by a short Q&A and panel discussion moderated by Amal Alhaag, a programmer at the RCMC, after which the event drew to a close. The symposium had asked its audience to think and then to rethink—to unpack and understand the historical construction of gender and sexuality in ethnographic institutions and the impact of this, and to be open to discussing the ways in which we can rethink it for the future. It did not offer a future solution as such, nor a clear answer to the central question of “how to un/engender the ethnographic object?” However, clearly defined solutions and answers were not the measure of the events success. Indeed, as Wayne Modest said in his introduction: “We have no solutions today… What we will do is open into a conversation about what it might mean to look at our collections differently” (quoting the speaker).

The value of the event is evident in that it pushed important and pressing, yet often ignored, questions to the forefront, and created a dynamic space for counter- and subversive- knowledge production and discourse. It was a valuable response to the global activism that demands museums rethink their collections and focus more on the interplay and intersectionality between gender, race, and ethnicity. It was, as Modest hoped it would be, a space for disturbance and critique. Personally, I left the afternoon with a head full of questions, issues, and topics for reflection, feeling that any notion of a natural social order had been debunked. Ultimately, the symposium was successful in making clear how we can, and should, combine cultural subjectivities with gendered and sexualised subjectivities, whilst acknowledging the multiple lenses through which we can view the ethnographic collection.

Look out for upcoming events in the RMCA’s Un/Engendered series.

Report written by

Hannah Vollam.

Collection development / Museology / Queer /

Agenda

Talanoa Forum: Swimming Against The Tide

An artist-led gathering by Yuki Kihara, co-hosted by LIMBO & Framer Framed in collaboration with National Museum of World Cultures

Network

Wayne Modest

Head of the Research Center of Material Culture

Fanny Wonu Veys

Curator Oceania

Maria Guggenbichler

Artist

Amal Alhaag

Curator

Shigeyuki Kihara

Artist