Mark Dion, Costume Bureau (2006)

Mark Dion, Costume Bureau (2006) Review: of the exhibition 'Costume Bureau'

Framer Framed: artistic engagement and confrontational activism

During the last few decades, socially critical artists have been positioning themselves as witnesses of their era, as advocates for realism and champions of a fair, sustainable, global society. Noble? Yes. Necessary? Absolutely. And in response, a number of museums and other art institutes are exhibiting their work with panache. Still, ‘artistic engagement’ seems to be no more than a hip term referring to a kind of art that adds only little and which is not embraced by the general public. This at least is the claim made by Hans Den Hartog Jager in his opinion piece from September 2014. This article provoked a media debate that exposed a sharp division of public opinion on the subject.

The Amsterdam-based Framer Framed is an organisation that has been actively promoting this kind of art for the past five years with success. The institute is run by Josien Pieterse and Cas Bool and since 2009 has gained a strong reputation as a sharp, inter-institutional discussion platform that approaches the position of artists, the representation of art and museum policy from various disciplines and innovative perspectives. Since 2013, Framer Framed has also offered a stage to transcultural art created by both western and non western artists whose work reflects conflicts and developments within society. In May 2014, Framer Framed opened their own space at the Amsterdamse Kop van Noord in the buzz of the multi-institutional Tolhuistuin complex. Pieterse and Bool do not curate their presentations themselves, but instead invite third parties to compose exhibitions for them, based on the Framer Framed programme lines.

Collaboration

Within this concept, Framer Framed’s recent exhibition, Costume Bureau, was the result of a collaboration with Roel Arkesteijn, curator of Museum Het Domein in Sittard. In this presentation, he focuses his attention on the importance of objective representation and subjective awareness-raising in a period of far-reaching globalism and changing perceptions within the (inter)national art scene. Arkesteijn believes in art that raises questions, provokes discussion and stimulates awareness-raising on pressing socio-political issues and conflicts elsewhere in the world. But he places equal value on work that connects people by building bridges between cultures as well as focusing on ecological problems by engaging with peoples’ capacity to empathise and put themselves in another’s shoes. Arkesteijn has selected works by eleven artists from the collection in Museum Het Domein. These works relate to each other in various ways in the exhibition at Framer Framed.

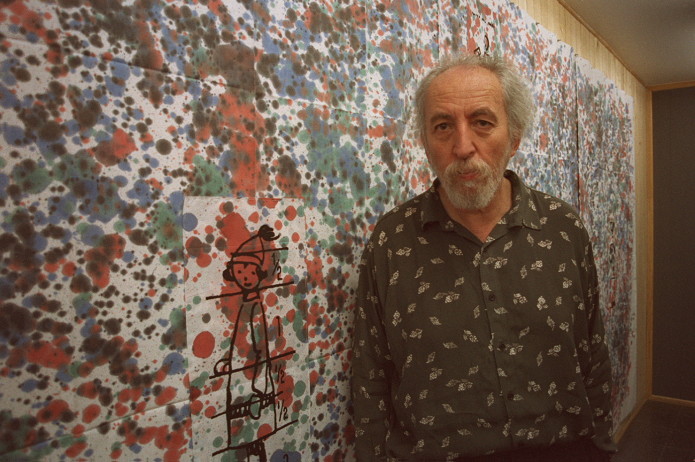

The name-giving leading role within the exhibition was reserved for the installation Costume Bureau by the American artist Mark Dion. Dion incorporated several outfits he actually wore into this installation. The installation symbolises the various ways in which artists currently approach their work, for example, as a researcher, an anthropologist, an archaeologist or biologist.

Economic ties

Another installation in the exhibition composed completely of clothing was created by the Dutch artist Roy Villevoye. Villevoye lives a few months every year on the south coast of Papua (Irian Jaya) in Asmat territory. The main theme of his work is the (economic) friction between the culture of the Papuans and that of the West. Where the average Dutch person would interpret this collection of faded and ravelled T-shirts as an expression of poverty, for the Asmat nothing could be further from their truth: the T-shirts are in fact a status symbol and have been torn deliberately in motifs reminiscent of traditional scarification patterns.

Arkesteijn also showed a video by a multimedia art duo, the American Jennifer Allora and the Puerto Rican Guillermo Calzadilla. In this video they highlight the ever-increasing mass production in China and its ecological fall-out from the perspective of a swimming turtle. The duo followed this turtle along a river and used their camera to capture the changing industrialised environment.

A related excrescence of the consumption society is addressed in the installation made by the Peruvian artist Jota Castro, who lives in Brussels. Five colourful childrens’ footballs, fabricated elsewhere by exploited children’s hands, were placed together, with some space between them on the ground. Each football was wound around with barbed wire. Castro, who used to be a UN and EU diplomat, gave up his diplomatic career and made a furore with his work as a very outspoken, activist artist and curator.

Othering

The vanished, the murdered, the dominated or the declared mad Other is also amply represented in Costume Bureau. For example, in the carnivalesque video by the Venezuelan Javier Tellez, in which psychiatric patients take part in a staged protest march, holding up banners with texts like ‘No racism intellectual!’. Physical and mental boundaries become blurred as Tellez shifts the focus: a real human canon ball flies – with identity papers – from Mexico into American territory.

Other boundaries are addressed in the work of Chilean artist Eugenio Dittborn and American artist Roger Ballen. Dittborn designed his own airmail envelopes. Not just to transport his large, foldable work, but also as an integral part of his installations. The envelopes connote customs authorisation and post marks, while the various labels nod to the title of the work, the applied technique and the locations where this exhibit has been previously shown. These envelopes made it possible for Dittborn to present his work outside of Chili during the regime of the dictator Pinochet. Dittborn incorporated various portraits into his composition, from children’s drawings made by his daughter to mugshots from police reports, so that it is unclear what the viewer is actually seeing.

A similar clouding of vision can be observed in the photos taken by the American photographer Roger Ballen. Ballen once travelled to South Africa for a mining project and ended up making it his home. He uses suggestive and macabre means to show the fringe of the white South African society, for example by photographing socially deprived locals in settings like a homeless shelter. Because he lets his subjects participate in the staging of the images, the photos acquire a raw, surreal and discomfiting character. With this approach Ballen’s work reveals another, unsettling side of the Rainbow Nation.

Images of genocide

Although Arkesteijn’s choice of title and the context of Dions work refer to a significant shift in terms of departure point and form of expression in contemporary artistry, it was arguably another aspect of the exposition that demanded even more attention: the calculating viciousness of human interaction. A deep impression was made by the complementary works of the Chilean Alfredo Jaar and the Flemish Sarah Vanagt concerning the genocide in Rwanda (1994) and the installation by the American Mel Chin, who highlights an aspect from the long drawn-out civil war in Sierra Leone (1991-2002). In Rwanda, between 500,000 and 1,000,000 people lost their lives in the space of just a hundred days , while 50,000 people were killed in Sierra Leone. In Rwanda ethnicity played the key role in the bloody struggle between the Hutu’s and the Tutsi’s; in Sierra Leone blood diamonds paid for the weapons used by the rebels against the ruling elite to force a transition of power. Here genocide was used mainly to instil fear and to help achieve the planned coup.

Mel Chin, who is known for his diversity in use of material and design, took a man-high trunk from a walnut tree and etched into it the frozen, anguished hands and the typical mask of a female water spirit from the Mende tribe, a tribal group that comprises 2 million people. At the bottom of the trunk, Chin incorporated an old-fashioned looking radio into the bark that is permanently dialled into a Sierra Leone radio station. Because of the time difference, the programmes reach the Netherlands only in the evening and were only heard by surprised visitors who came to see the exhibition when it was open in the evenings from Thursday to Sunday.

In her work from 2004, Sarah Vanagt shifts the perspective from the viewer to that of a class of Rwandan school children. When their teacher asks them what happened in 1994, some of the children look dejected, while others beam and raise their hands, eager to answer. The teacher does not mention Hutu’s or Tutsi’s, but instead describes the nature of the violence with the terms itsembabsembe ‘n itsembabwoko: murdering people on the basis of their ethnicity in order to wipe them out as a group. In this way he manages to render a very dark subject lighter in the ensuing discussion. Vanagt captured this moment and sends out a message that is at turns horrific, surreal and hopeful. This work should be put on the school curriculum in a subject such as History or Social Studies.

In 1994, Alfredo Jaar took about three thousand photos in Rwanda, after the genocide. Once he returned home he found almost all of them to be useless because they failed in his eyes to express the inconceivable nature and scale of the war. His project ended up showing only five of those works, and of these five, a large triptych was shown at Framer Framed. On the far left was a photo depicting an expansive tea plantation; to the right of it a photo of a hazy bend in a road, fringed by woods and a great white cloud hovering in a blue sky. Under the cloud a tree and the cross of a little church was visible. In-between, to the right of each photograph hung small, legend-like black prints on which were drawn white landscape lines that corresponded to the photos. At first sight the work was unimpressive; until the visitor approached to look more closely at the black prints. Jaar exerts a subtle control to transport the viewer through the narrative of the photos and prints in a gruesome hunt and game story that increases the tension as it goes along. But a visual confrontation remains absent because the ‘discovery’ of the drama occurs in an almost filmic fashion completely in the heads of the audience.

Subsidy for consciousness-raising?

However stimulating the exhibited work might be, and however relevant the social engagement of the artists is, a confrontational exhibition like Costume Bureau raises some critical questions. In practice, does such a presentation achieve the desired effect of more understanding, consciousness-raising and connection to others? And is that a goal in itself or a fortuitous side effect? And does the work even reach the public that the artists, Arkesteijn and Framer Framed want to reach? Shouldn’t such critical exhibitions be given a permanent place in the curriculum of secondary school students to promote artistic and social development? Or is it enough to reach a small but critical group of art-loving adults, which is the situation as it stands?

Arkesteijn believes that socially-critical art has a different status to work that is valued purely for its aesthetic qualities. Socially engaged art is seen as un-sexy, it is considered commercially uninteresting and does not attract long lines of visitors. Socially engaged art demands of the viewer that extra interest, honest attention and (self) reflection in order to get the most out of it. This can be uncomfortable for those who see art as a piece of wall decoration and do not want to think about the ‘who, what, where and why’ of the work being consumed. It is a conscious confrontation in the form of identity correction, a method employed by a fairly new artistic movement that Arkesteijn feels is strongly represented by the artists exhibited by Framer Framed.

For Arkesteijn there has been a bitter aftertaste to the Costume Bureau exhibition which can also be read as a sample of the purchasing policy that his museum has pursued during recent years. From 1 January 2015 Museum Het Domein will be incorporated into a new organisation together with the previous Sittard institutions that focus on local culture. It is unclear whether Het Domein can preserve its own unique identity and exhibition programme. In Amsterdam-Noord the situation is less worrisome: Framer Framed will be supported for the next two years by the Mondriaan Fonds, a fund for the arts that approved the projected programming for the coming years.

Costume Bureau was exhibited at Framer Framed from 10 October until 25 November 2014.

Participating artists

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla, Roger Ballen, Jota Castro, Mel Chin, Mark Dion, Eugenio Dittborn, Alfredo Jaar, Javier Téllez, Sarah Vanagt and Roy Villevoye.

- Museum Het Domein

Links

Collection development / Museology /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Costume Bureau

A collection presentation of Museum Het Domein, curated by Roel Arkesteijn

Network

Roel Arkesteijn

Curator

Eugenio Dittborn

Artist

Alfredo Jaar

Artist, Filmmaker

Javier Téllez

Artist, Filmmaker

Roger Ballen

Artist, Filmmaker

Jota Castro

Artist

Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla

Artists

Sarah Vanagt

Artist, Filmmaker

Mel Chin

Artist

Mark Dion

Artist