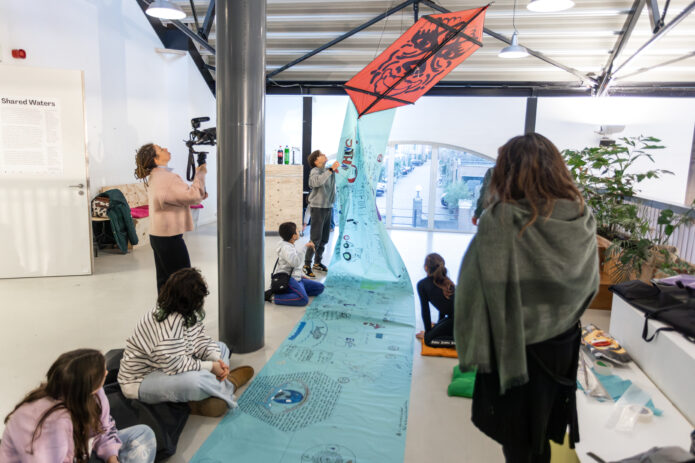

Shared Waters opening in Amsterdam. Photo: Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed

Shared Waters opening in Amsterdam. Photo: Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed Shared Waters: Hoe het Camissa Museum in Kaapstad haar grenzen verlegt naar Amsterdam

In January 2024, Framer Framed presented the result of an exciting educational exchange project between students in Amsterdam and Cape Town, South Africa. The presentation, in the form of an exhibition, showcased the students search for their roots and desire for multicultural connection. Before the opening, Evie Evans spoke to board members of the Camissa Museum, Calvyn Gilfellan and Stephen Langtry, about how the project with Framer Framed began.

Test Evie Evans

In May 2023, Framer Framed embarked on a new international educational project in collaboration with the Camissa Museum in Cape Town, South Africa. The first sessions kicked off in Amsterdam, hosted by Dutch-Ukrainian artist Karine Versluis. In September 2023, the project continued as an 8 weeks long in-school program at Kiem Montessori in Amsterdam, led by Adjoa Kpeto, Cherella Gessel and Rienke Enghardt. However, the project Shared Waters has been years in the making. I spoke to two of the board members to find out more about the museum and why they wanted to undertake this exchange project with Framer Framed.

Calvyn Gilfellan begins our Zoom call he begins with an infectious enthusiasm, showing me his whereabouts at the Castle of Good Hope as we speak. As CEO of the heritage site, it’s not an unusual place for him to be, yet it already demonstrates his goal of wanting others to experience a new dimension to a space of immense history and suffering. He begins by contextualising his own position as a scholar of geography, environmental studies and cultural heritage tourism that informs his role as the Chair of the Board of the museum.

Students at the Camissa Museum at the Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town, South Africa

Fellow board member Stephen Langtry begins on a more sober note: ‘The history of colonialism in South Africa begins in Cape Town.’ The Camissa Museum is a unique place that tells the story of those who would have been classified as ‘coloured’ during apartheid in South Africa. A blanket label which ignores the dense diversity and cultural heritage of the people which it names. The museum, with a great focus on educating young people, asks the question of its local visitors: Who are we beyond the ethnic categories that have been foisted upon us? The founders choose the name Camissa after the Camissa River of Cape Town, meaning ‘sweet water for all’ in the language of the indigenous people who lived alongside it. It’s the perfect metaphor for the narrative of the museum – with its diverse tributaries which come together as one. According to the museum website:

‘Camissa Africans cannot be defined by colour, features, ethnicity, or race but by a common experience of facing and rising above systemic adversity and a range of crimes against humanity – colonialism, slavery, ethnocide and genocide, forced removals, de-Africanisation and Apartheid. Just like the Camissa River was forced underground, so were the Camissa Africans.’

The contents of the museum are based on years and years of archival and historical research, consultation and public participation. Calvyn Gilfellan met with one of the co-founders Angus Leendertz, along with South African Ambassador & political activist Robina Marks, at Galle Fort (a Dutch colonial fort) In Sri Lanka almost five years ago. ‘It was there we concretised the idea of creating a museum based on identity’, he explains. One of their inspirations was Patric Tariq Mellét, the revolutionary author of The Lie of 1652: A Decolonised History of Land. His book outlines 220 years of resistance and a history of migration to the Cape by Africans, Indians, Southeast Asians and Europeans.

As Calvyn tells it, the founders wrote a formal proposal which was immediately accepted by the board of the Castle of Good Hope. The Camissa Museum was launched virtually during the COVID-19 pandemic, and as a physical space half a year later. The space is important because, according to Calvyn, 90% of museums in South Africa focus only the country’s colonial legacy or its apartheid history. Calvyn emphasises, ‘we are grappling with the question of identity in a tactile and integrated way’. Considering many museums struggled to adapt to digital during lockdown, I found it significant that the Camissa Museum succeeded in the opposite. I probe more into why they insisted on a physical space, especially one with an extremely colonial and violence history.

The museum is situated within the Castle of Good Hope, a fort built by the Dutch East India Company in 1666, replacing the first Dutch fort built by colonist Jan van Riebeeck, the first Commander of the Cape. Calvyn explains, ‘There are 6 or 7 other museums in the Castle, either complimentary or contradictory to what is in the space and which deconstruct the traditional idea of a museum.’ Calvyn specifically uses the term “decolonising” as an active verb, a process without end. ‘We admit it’s a space of atrocity…and that cannot be presented unproblematically”’ The new narratives of the Castle, including the Camissa Museum, aim to be inclusive and empowering for its visitors, enabling them to reclaim the space.

The decolonising comes from a sense of ownership, deeply interrelated to the ancestry, personal history and the Dutch colonial legacy. ‘It’s important for us’, Stephen notes, ’to deal with a place of trauma and transform it to a place of healing’.

However, whilst it’s important for the Board that people can return to the physical space of the museum, Calvyn argues ‘The Camissa Museum is not confined by its borders of the square room, it’s also outside the castle and outside in the communities. The mountains, the streams, there’s always a link with the spatial environment around it and the communities around…We call it a museum because there needs to be a space where these discussions can take place.’ And they do this by creating a strong educational foundation to the museum and initiating outreach projects with other partner organisations in Cape Town.

Stephen expanded on this ‘we’re currently in the process of completing the permanent exhibition of the museum, but the most important part for me is to ensure that the museum continues to do outreach programs targeting young people who are often not aware of the stories we tell. Bringing them to the museum on a regular basis, taking them through workshops to explore the history but also their own personal stories and how it relates to the legacy of colonialism.’ One of these programmes is Shared Waters, but why Framer Framed? Calvyn explained that co-founder of the museum Angus Leendertz had two reasons for looking towards Amsterdam. Angus was ‘familiar with the work Framer Framed has done, and has experience living and working in Amsterdam. The other part is that it’s unavoidable – when talking about colonialism and the history of South Africa, South African’s are very aware of the role of the Dutch in that.’ He was drawn to the decolonial work, or the approach to decoloniality that Framer Framed is doing.

Mary Sibande, Conversations with Madam CJ Walker (2009), installation view of the exhibition Re(as)sitting Narratives (2016). Foto: Eva Broekema

Framer Framed is familiar to collaborations with partners in South Africa. In 2016, the Framer Framed exhibition Re(as)sisting Narratives, curated by Chandra Frank, explored the legacy of colonialism between the Netherlands and South Africa. The presentation was the result of two-years of research with partners, District Six Museum and Centre for Curating the Archive. The contemporary artists in the show – Mary Sibande, Sethembile Msezane, Mohau Modisakeng, Athi-Patra Ruga, Burning Museum Collective, Toni Stuart & Kurt Orderson, and Judith Westerveld – offered powerful perspectives on race, gender, memory and trauma. The works were eventually shown both at Framer Framed in Amsterdam, and at the District Six Museum Homecoming Centre in Cape Town. District Six, which was also mentioned by Calvyn Gilfellan, was an area of Cape Town whose inhabitants were forcibly expelled by the apartheid government after the area was designated for white citizens only. The museum was formed in 1989 to commemorate the district and strength of its community.

Within the context of Re(as)sisting Narratives, Framer Framed collaborated with organisation, Face to Face for international peer education. Two schools in the Netherlands and South Africa were connected and students worked together in online workshops. In fact, Framer Framed is hardly a stranger to education exchange programmes. When the exhibition space was first opened with the project, Crisis of History in 2014, it was accompanied by the Irbid Exchange international education programme. During this project, young people from the refugee shelter AZC in Almere were put in contact with peers in the refugee camp Irbid, Jordan. The participants entered into a dialogue via Skype, the exchange of artistic works by post, and a Tumblr account which you can still view today.

Since 2020 we have been working with the art school, Funda Community College in Soweto for the Decolonial Futures Exchange Programmes. As another hybrid exchange project, this format – in collaboration with Sandberg, Rietveld Academie – informed the planning of Shared Waters. Framer Framed hosted collaborative workshops online, and shared with artists in Soweto.

However, Shared Waters is still considered a sort of pilot project. It’s new initiative for young people to explore the personal (and political) elements of colonial history from two perspectives: that of the museum and an art space. As early as 2020, Angus was already in talks with Josien Pieterse, co-director of Framer Framed. Supported by Dutch Culture, the project aims to encourage young people to explore their family history and global connections in tandem with their peers in Cape Town. Participants will come together to exchange stories and experiences, eventually creating artistic works which will be presented in January 2024 at the Camissa Museum. Calvyn gushes about the project, ‘I had the privilege and the power to allocate the space for such an important project, with the support of Dutch Culture And I’m really looking forward to completing this last part of the exhibition.’ He comments admirably on the current South African participants, ’there’s clearly a passion and a hunger amongst the participants to share…the kind of questions they ask, the confidence they build up’. Participants in Amsterdam will share their own work simultaneously at Framer Framed.

Shared Waters workshop at the Camissa Museum, Cape Town

The water metaphor beginning with the Camissa Museum is extended to Shared Waters. The Dutch colonial enterprise was a naval one; traversing the sea with commerce and the slave trade. But Stephen was resolute in mentioning the expanse of the Dutch East India Company in Asia, too, not just Africa, South America and the Caribbean. Many indentured workers were transported from Indonesia, India and Vietnam. Water is a boundless body, a type of space that connects many lands and cultures. The Shared Waters project by name encourages participants to re-evaluate their understanding of landscapes, spaces and how that informs their own history and identity.

Although it’s a pilot, and the first time the Camissa Museum has ever done a project like this, Stephen is optimistic. ‘There’s a lot of excitement in Cape Town from the youth that we’re working for two reasons: one is just that when young people get together in groups, the energy unleashed is always great to witness ,but for them, it’s also the opportunity to interact with young people in the Netherlands. Obviously it’ll be great if they can be in the same room but the way it’s done at the moment, virtually, is still good. It’s providing great opportunities to learn about other people.’ And regarding the outcome of the exchange? ‘We envision [the pilot project] as a creative arts project,’ Stephen answers, ‘So at the end of the workshops the young people will have produced some works. We might have a series of artworks (painting, sculptures, performing arts, music, poetry) to represent what they have learnt and experienced.’

Shared Waters workshop at the Camissa Museum, Cape Town

The results of the exchange are yet unknown, though the project signifies an important act for young people in both Amsterdam and Cape Town. They are able to explore their identities, how they see themselves and how they see the world in an open space. They can ask questions about their family history and colonial legacies and have the initiative to search for the answers themselves, or with others. By taking a creative approach, the results are limitless. New connections and new narratives can be formed, informed by colonial links but not limited to them, across the globe. The shared waters wash over borders and breach boundaries, making them undetectable, allowing us to focus on our commonalities and junctures that come together – just like a stream flowing into a river.

Evie Evans

December 2023

Shared Waters opening in Amsterdam. Photo: Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed

Educatie / Gedeeld erfgoed / Koloniale geschiedenis / Museologie / Zuid-Afrika /

Exposities