Workshop Report: Hybrid eXperience

by Julia Wilhelm

April 2021

Set to release in Spring, 2022, Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices wants to shed light on practices in specific communities where collaboration is common in daily life; where art is seen not only as a self-contained profession, but also as ways of living and being.

The publication process is accompanied by a series of online workshops/events in which we invite participants to gain insights into the dialogues, engage with the contributors, and co-develop design frameworks for the publication prior to its physical manifestation.

Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices is a collaboration of Framer Framed and the Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA).

Introduction to the Workshop

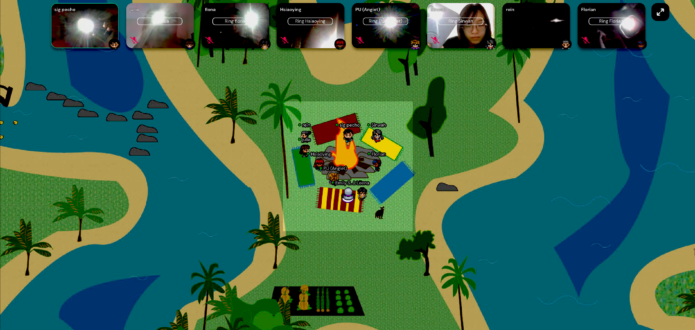

The workshops take place on the platform gather.town, which is often referred to as a mix between Pokémon and Zoom. The interface allows participants to walk over a virtual map with an avatar and encounter other avatars/participants, whose camera will turn on when they approach each other.

Just like in real life, multiple groups can gather in the same space and have conversations and avatars can walk around, encounter others and have one-on-one interactions. Interactive objects that contain videos, images, quotes, games, or links to other websites are scattered across the space, allowing the platform to serve as both a means of communication and a growing, interactive archive.

For this series of workshops, we created an archipelago as virtual background, consisting of different islands connected through pebbles. The virtual space refers to the landscape of Southeast Asia, from where many of the contributors originate, and functions as a metaphor for fluidity between land and water, fluidity of thoughts, and as a space that invites playfulness. In our archipelago, visitors can find excerpts from the publication, related videos, and other interactive objects.

Workshop: Hybrid eXperience 1 & 2

28 March & 4 April, 11:00 – 13:00

As our workshop facilitator Sig Pecho introduced in the beginning of the event, the main intention of our first two workshops was to offer a “time-X-space” for encounter and exchange, discuss topics addressed in the publication and harvest doodles and scribbles. To familiarise the participants with the practices that inspired our workshop, they received booklets with excerpts from the dialogues beforehand.

After gathering around the fireplace on the main island, Sig welcomed the participants with a short introduction about the significance of the “X”. Sig is part of a performance collective Komunidad X, which sees “X” as a point of encounter, exchange, and transformation. The “X” functions as a meeting point, a crossing of two lines. “X” is also the key that participants need to press to interact with objects on gather.town, and the shape of the main island of the archipelago with the fireplace at its center.

Dream Catcher

After the coordinator Emily Shin-Jie Lee explained the context of the publication project, we walked to the first site of encounter on the North-East of the archipelago, a fisher net hanging from a tree, referring to the common association between the sea and the unconscious/dreaming.

Through pressing “X”, a whiteboard embedded in the net appeared, which could be used to take notes and make sketches. Once all the avatars had found their way to the cozy spot next to the beach, Sig Pecho shared some thoughts on the dialogue he had had with curator Mayumi Hirano for the publication.

“When this project started out, Mayumi and I shared our hopes of being together in a better place where we can commit to the exchange of ideas, practices, and experiences. The pandemic however led us to become resilient with our virtual gatherings. We had our processes or methods that were both new to us. In this exchange, we learned a lot, we shared so much, but we also expressed how we dreamed of better conditions in the future. What are the values of dreams, of collectively dreaming together?”

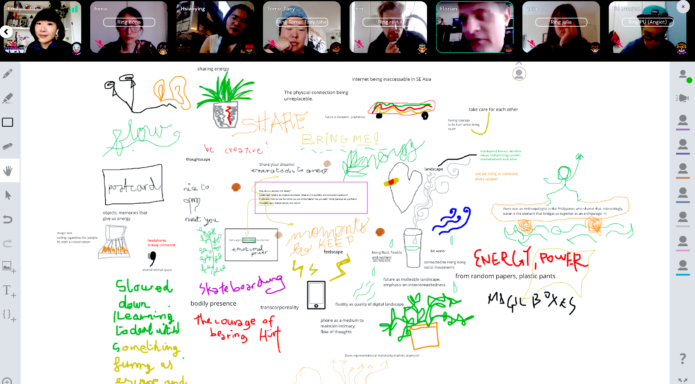

In line with his reflections on their conversation, he invited the participants to dream up a post-pandemic future and presented the notion of landscape, thoughtscape and feelscape that are relevant both in the context of his theatre-practice and as tools for collective imagination. [1] To make this collective dreaming more playful, Sig proposed to play the game Bring Me, in which participants had 30 seconds to look for an object that connects to their dream(s). The participants were invited to share the stories behind the objects they brought and to sketch and note on the whiteboard.

One participant brought a Bialetti percolator, referring to the act of sharing a cup of coffee, but also to the fact that much coffee is still produced in neo-colonial frameworks in exploitative working situations, which he would like to see changed in the landscape of the future.

Another participant, equally emphasizing the act of sharing, brought her small silver cigarette rolling box that often catches the curiosity of passers-by on the street and enables her to engage in conversations with strangers while sharing a cigarette. Still another participant brought their phone, which is the medium through which they relate to their close-ones and through which they can experience intimacy.

Some participants brought living beings such as a plant, or a sour-dough culture, beings that need to be maintained and taken care of to thrive and remind us of our interdependencies to other species. Another person shared a collection of poetry called Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz, which gives her courage and hope, akin to another participant who found strength in music and shared a song during the session.

A glass of water served as a metaphor for fluidity, for futures as malleable landscapes, which connects to the sharing of a non-object, the absence of an object, inspired by the story of the king of “No-Form” by Chinese philosopher Chuang Tzu. [2] While one person was talking, the others were drawing, noting, writing down comments and questions, or reacting on other people’s sketches and thoughts, resulting in a growing web of interconnected images and texts.

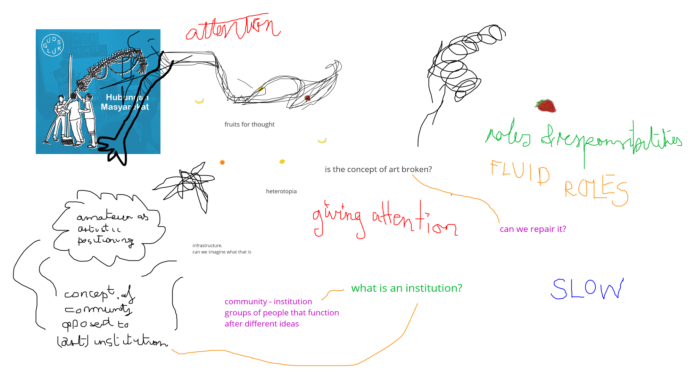

Fruits for Thought

After our intimate conversations, participants had time to roam around to find some “Fruits for Thought”—lemons, bananas, oranges, and strawberries scattered around the island, which contained small excerpts, images, or video clips relating to the publication. Participants were then invited to bring the fruits back to our next meeting point – a fruit-bearing tree in the South-West of the islands.

After everyone had arrived, Sig talked about one of the methods he experimented with during his exchange with Mayumi. He told that while they had a conversation on zoom, one of them was talking and the other one was transcribing and had to concentrate thoroughly on what the other person said. He suggested that the participants might use the present whiteboard to document the reflections on the fruits, be it in text or in a more visual way.

Emily guided the following sharing of fruits. Many participants could relate to a quote by Brigitta Isabella, hidden in a lemon that could be found in a small tent. Brigitta is engaged with different knowledge production platforms and connected to the Yogyakarta-based collective KUNCI. In her dialogue with Rieneke de Vries, a social and creative worker based in the Netherlands and co-founder of We Sell Reality, she describes how she connects with the word amateur in her practice:

“We become a translator, a friend, an artist, a writer, a cook, a gardener, a teacher, a student perhaps as an eternal amateur. To me the word amateur harnesses the affective side of doing things together for collective pleasure/joy and resist the dulling practice of “professionalism” or “business as usual.” Being an amateur also allows me to learning through the process instead of assuming I always know exactly what am I doing or about the people who I work with.”

This quote connects to the multiplicity of roles many participants inhabit in their own work, but also to the idea of having a non-one-directional practice, that some voiced. As Brigitta’s conversation partner Rieneke wrote in one of her emails:

“You wrote: “What happens/what is the implication when they have the label of “artist”? My answer: ” I don’t care about the label artist at all. We, (We Sell Reality), use different labels in different situations. Sometimes we call ourselves a design collective, sometimes an art collective, sometimes I call myself a social worker (when I call a lawyer for example), sometimes we say we are a ‘studio’ or a shelter. Sometimes we make ourselves big, sometimes we have to be small.”

In line with this quote, the participants thought of artistic practices rather as tools for social change than as end-goals and agreed that the label ‘artist’ can also function as a tool, for example to apply for funding or to get access to certain infrastructures.

Many participants were interested in the idea of ‘adapting’ one’s practice and the labels one uses to specific contexts, an approach which highlights the ecosystems and larger societal frameworks in which one operates, aspects that are too often neglected. Different contexts require different approaches, different responses — this resonates with Bunga Siagian, another contributor of the publication who considers ecosystems as

“a context of creation that, in its process, is not autonomous or isolated — inseparable from its relations with others or from its social and political nuances. An awareness of such interdependency reveals a new perspective on the different roles and dynamics of different subjects within the context of creation”

A question some of the participants addressed is whether this acknowledgment of embeddedness and reactivity towards the environment is sufficiently discussed in arts education. Another participant reflected on a banana that contained an image that Chen Wei-lun, a member of the collective Trapped Citizen who organises events and discussions, shared in his conversation with Wok the Rock.

The image shows a large group of people, holding up signs and raising their fists. The photo depicts a protest called db Test Vol. 2, organised with the Daguan Community that had built a network of mutual aid in New Taipei city yet ended up being forcefully evicted. Here again, art and music function as tools not only to achieve a specific goal, but also to create joy and solidarity among those present.

Besides thinking of art as a tool for social change, many participants were interested in Elaine W. Ho’s proposal to think of art as ‘the practice of giving attention’:

“I recently had a meeting with members of the Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination, and they describe art as the practice of giving attention. This struck a chord with me, because it shifts the relations between artworks as objects of contemplation, and the processes between theory and praxis that we may call creation. It also begs the question of who it is we are giving our attention to, and who it is that might deserve more attention.”

Speculations about Infrastructures

The sharing of our fruits resulted in a conversation on whether the concept of art wasn’t already too entangled with the speculative art market, institutional infrastructures and the idea of the solitary genius, one participant even raised the question if the concept of art was broken and if it was useful to make the effort to try to repair it. Can we come up with our own infrastructures, based on collectivity and solidarity, as opposed to the institutional art-world?

Both institutions and collectives are ultimately composed of groups of people, but the concepts and ideologies after which they operate are radically different. We also discussed the possibilities of online platforms like gather.town as tools for encounter and collective organisation, to work and live together despite being physically distanced. But those platforms are often in private ownership, the devices through which we access them are made and tailored by private companies. What alternatives are there?

We ended our adventure with a moment of reflection around the fireplace and shared what we took from the space. For many of us the exchange was very valuable and the discussion under the fruit-bearing-tree spread seeds in our minds. To say goodbye and honor each other’s presence, Sig led a short closing-of ritual, during which we were invited to shine into the camera with the torch from our phones, creating a starry sky of frames and faces floating over the landscape of the archipelago.

After the workshop was officially over, email addresses were exchanged, people kept on discussing, went to play piano or look for some interesting fruits hidden on the archipelago. The space will stay open, participants are invited to come back and bring friends whenever they like.

*We would like to thank all of the participants who joined the event and their creative contributions.

Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices is a collaboration of Framer Framed and the Willem de Kooning Academy.

Contributors of the publication: Elaine W. HO, Zoénie Liwen Deng, Rieneke de Vries, Brigitta Isabella, Mayumi Hirano, Sig Pecho, Wok the Rock, Willy Chen Wei-Lun, Bunga Siagian, Ismal Muntaha(JaF), Dicky Senda

[1] In this context, the term landscape refers to the physical build-up of the imaginative scenery, and the ecosystems that form it; feelscape is an invitation to think the emotional journey that gets you there; thoughtscape is connected to the shared values and the culture of this imaginative future.

[2] “The South Sea King was Act-on-your-Hunch. The North Sea King was Act-in-a-Flash. The king of the place between them was No-Form. Now South Sea King and North Sea King used to go together often to the land of No-Form and he treated them well. So the two consulted together. They thought up a good turn, a pleasant surprise to No-Form, in token of their appreciation. ‘Men’, they said, ‘have seven openings: for seeing, for breathing, for hearing and so on. But No-Form has no openings. Let us make him a few holes.’ As so they put holes in No-Form, one a day for seven days. And when they finished the seventh opening, their friend lay dead. It is then said: ‘To organize is to destroy.’”

Burgerschap / Action Research / Community & Learning / Kunst en Activisme / Politiek en technologie / Social Practice / Zuidoost-Azië /

Agenda

Boekpresentatie: 'Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene' & 'Be Water, My Friend'

Een vreugdevol gesprek over schrijven, lezen en boeken maken op documenta 15, Kassel

Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene 4: Musical Hangout

Online workshops voor het gemeenschappelijk ontwerpen van publicaties

Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene 3: Doodle Lecture

Online workshops voor het gemeenschappelijk ontwerpen van publicaties

Art for a Citizen Scene 1&2: Hybrid eXperience

Online workshops voor het gemeenschappelijk ontwerpen van publicaties

Netwerk

Bunga Siagian

Singer-songwriter and producer

Zoénie Liwen Deng

Kunstschrijver en onderzoeker

Chen Wei-lun

Gemeenschapsbouwer en kunstenaar

Ismal Muntaha

Kunstenaar

Dicky Senda

Schrijver en voedselactivist

Elaine W. HO

Kunstenaar

Wok The Rock

Kunstenaar en muzikant

Rieneke de Vries

Kunstenaar en Sociaal Pedagogisch Werker

Brigitta Isabella

Activist en onderzoeker

Mayumi Hirano

Freelance curator