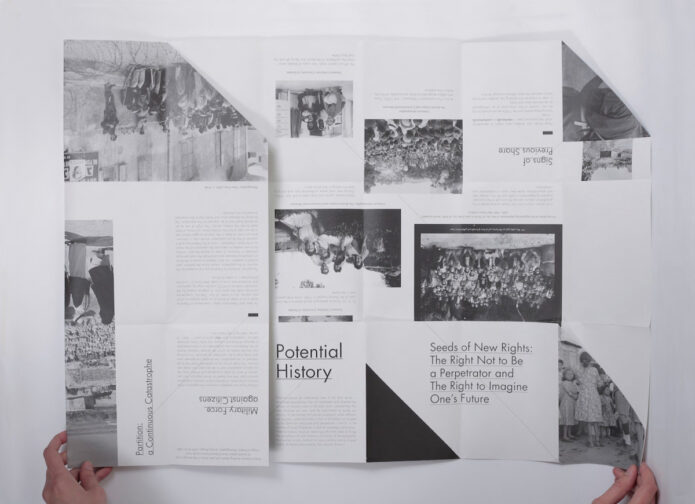

'Potential History' (2019) by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

'Potential History' (2019) by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay Rapport: Decolonial Futures met Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

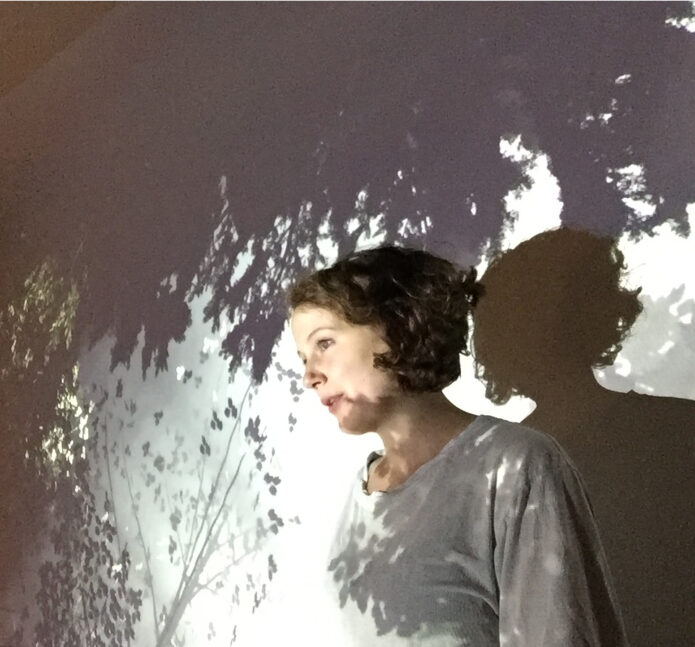

This weeks guest lecturer in the Decolonial Futures series; Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, is a documentary filmmaker, curator, photography scholar – as she calls herself, and Professor of Modern Culture and Media and the Department of Comparative Literature, Brown University.

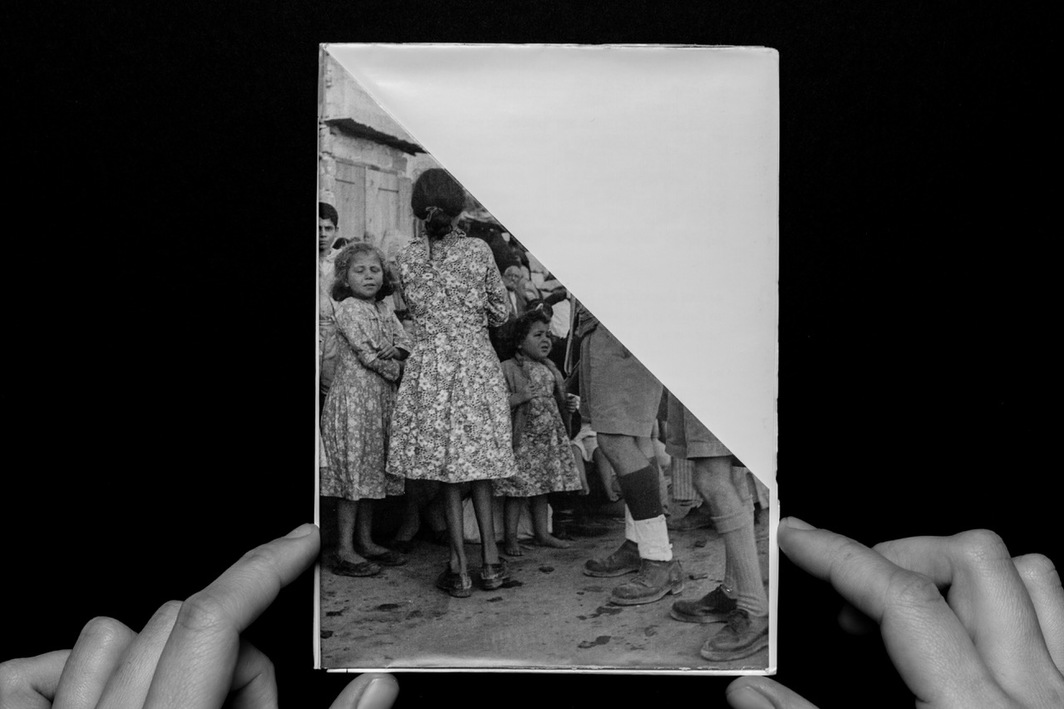

Potential History (2019) by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

During the third session of Decolonial Futures two films where discussed: Statues Also Die (1953) by Chris Marker & Alain Resnais and Un-Documented – Unlearning Imperial Plunder (Sans-papiers, désapprendre le pillage impérial, 2021) by Ariella Aïsha Azoulay.

Shot nearly seventy years apart, and yet witnessing petrifying evidences, the two films orbit around dislocated histories encompassed in the presence of African art and artefacts in European museums. Although different in intent and positionality, the filmmakers invite us to rethink the continuation of imperial violence against claims to humanity and rights of movement and to decipher the political apparatus allowing for their continuation as well as our collective responsibility towards the status quo. Both documentaries highlight the museum’s claims to the apolitical, arguments which are poetically woven to reveal their active roles in framing and negotiating histories and their social manifestations. The points of contention are juxtaposed with the seeds of imagination out of which colonial mechanisms that are re-enacted hold the potential to be disentangled.

In preparation of the discussion Ariella supplied a reading list consisting of three articles:

Understanding the Migrant Caravan in the Context of Imperial Plunder and Dispossession,

The Captive Photograph, and

Market Transactions Cannot Abolish Decades of Plunder.

Besides the articles the participants where asked to watch the two mentioned films beforehand.

(text continues below)

Hearing only the lecturer’s introduction, many questions arose from the participants’ side. Ariella Aïsha Azoulay mainly introduced her views and thoughts through presenting her book Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism (Verso Books 2019), which focuses on unlearning imperialism. Although often being presented as a documentary filmmaker, she actually rejects the genre of ‘documentary’. This stance stems from questioning the future as such (decolonial future included).

The lecturer immediately satisfied the audience’s curious and even puzzled looks by diving into her thoughts about the concept of temporality as an abstract technology of colonialism. Future, for Azoulay, represents an ambivalent term, which is posed by the colonial mindset. It alienates the past, making the responsibilities of imperial history non-existing and disconnected from the present. Instead, Ariella proposed intervening in the past, thus decolonizing it. Coming back to the statement introduced in the beginning, Azoulay explained how the documentary, therefore stands as one of the imperial practises of focusing on the past and making the events that are realistic even in today’s world as something that was pre-established or left in past, irresponsible for current struggles of the (once) colonised.

This inspiring view on imperial history and colonisation in general, Azoulay explained as well through spatiality and the body politics, as other two abstract technologies of colonialism. However, the technologies by which we are constantly getting colonised expand beyond the abstract, Azoulay highlighted. Museums, archives and institutions alike represent the perpetuating technologies of colonial thought. These are in close relation to the technology of temporality and the body politics, as they represent the past, the history, as well as artefacts and shape the image of the colonised peoples and their material culture – from a colonial perspective. Furthermore, the lecturer highlighted that it is vital to mention how much such technologies also leave a trace on the self-representation and identity of the colonised.

As a photography scholar, Azoulay also turned to her standpoint on photography through the prism of colonial studies. Taking the sole invention of photography, and the camera as a colonial concept, considering the time and circumstances it was invented in, Azoulay defines photography as the infrastructure of imperialism. It was later also a vehicle that further enforced colonial mindset and practises (e.g. documenting the Indigenous peoples from the Eurocentric perspective, thus enforcing the colonial gaze).

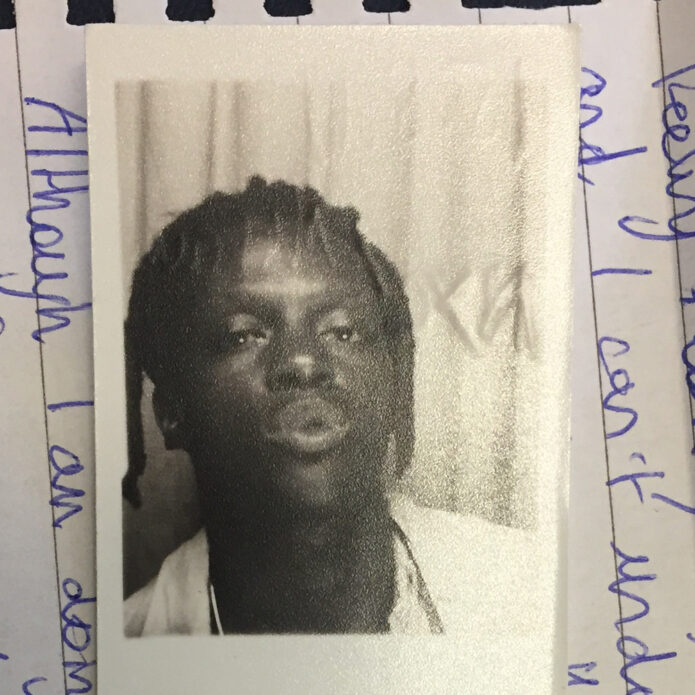

As one of the examples of photography as the infrastructure of imperialism, but also of (de)colonising institutions, the workshop participants were presented with the case study from the photograph published and owned by Harvard University. It was, namely, a photograph representing the study done on white versus black people (from a racist perspective) in the XIX century, while the subject depicted was an illegally enslaved man (colonial enough to say that at some time, enslaving any people(s) was legal), brought to the US from Congo after the abolition of slavery. After researching her roots, the man’s great-granddaughter requested ownership over a photograph, yet was refused. By showcasing this striking case, Azoulay’s statements seemed to have painted a clear picture in the participants’ minds, where some of them expressed personal examples or questions that still tackle their self-representation.

This intense, but interactive workshop filled with sentences of which almost each could be quotable seemed to have given a new perspective of the colonial legacy and imperialism structures existing in our minds, hence our world. Azoulay managed to tackle the topics, which seemingly do not interfere with the questions of colonialism, yet tell so much about it. Considering the participants’ engagement, the lecturer of the third session’s workshop triggered many unopened drawers belonging to the complex concepts of colonialism and imperialism. With such an insightful and eye-opening workshop, the first term of Decolonial Futures 2021-2022 has finished and left our participants to contemplate decoloniality, as well as the ways to interfere with our present system, in order to dismantle the chains of colonial thought and practises.

About Decolonial Futures

Decolonial Futures is an exchange programme organised between the Sandberg Instituut, the Rietveld Academie and Framer Framed in Amsterdam as well as Funda Community College in Soweto, South Africa. As a type of archive to connect the parallel course in Amsterdam and South Africa, highlights of the discussion and reading lists are posted each week on the website of Framer Framed to make decolonial knowledge and practices more accessible to everyone.

The 2020-2021 programme

The 2020-2021 programme was decided in two terms. During the first term students students working across the disciplines of art and design familiarised themselves with Funda’s socio-cultural context which is inseparable from the rich history of Soweto and South Africa at large. Parallel to sessions in Soweto, the participants at Framer Framed in Amsterdam – led by curator and poet Ibrahim Cissé – examined their understanding of historical and hegemonic systems of knowledge production. The students began to explore digital methodologies which could be used to create dialogue and engagement between former colonised nations and former colonising nations.

In the 2020-2021 second term, Decolonial Futures collaborated with sonsbeek20→24 under their curatorial framework which focuses on labour and the sonic. Over the course of 2 months students looked into traditional forms of African storytelling and the creation and transfer of knowledge via music and songs in various different cultures.

More on 2020-2021 first term

More on 2020-2021 second term

The 2021-2022 programme

The 2021-2022 programme focuses on documentary as a medium of both de/colonial practices of making, representing and looking. This year, Decolonial Futures will also be punctuated by the Winter School, a 10 days long programme in 2022 in which participants from South Africa and the Netherlands will have an opportunity to meet in Amsterdam and to collectively ponder on the materialisation of the colonial remnants and decolonial strategies in everyday life. The ongoing work and discussions will be restituted to the public at the end of the programme.

The organisational team consist of Dorine van Meel and Ibrahim Cissé (Sandberg Instituut / Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam), Simangaliso Sibiya and Phumzile Nombuso Twala (Funda Community College, Soweto) and Evie Evans & Josien Pieterse (Framer Framed).

Community & Learning / Gedeeld erfgoed / Koloniale geschiedenis / Museologie /

Agenda

Decolonial Futures Workshop Series: The Womb Republic - How to Rebirth

Een cultureel uitwisselingsprogramma met Funda Community College, Soweto, Zuid-Afrika

Decolonial Futures Winter School: Creating Space for a Hundred Flowers to Bloom

Een cultureel uitwisselingsprogramma met Funda Community College, Soweto, Zuid-Afrika

Decolonial Futures: Workshop met Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

Eerste semester van het Decolonial Futures programma 2021-2022

Decolonial Futures: Workshop met Aditi Jaganathan

Eerste semester van het Decolonial Futures-programma 2021-2022

Decolonial Futures: Workshop met Sara Blokland

Eerste semester van het Decolonial Futures-programma 2021-2022

Decolonial Futures 2020: Tweede semester

De aftrap van tweede semster van Decolonial Futures is open voor het publiek

Decolonial Futures 2020: Eerste semester

Oproep voor deelname aan het eerste semester van het Decolonial Futures Cultural Exchange Programme 2020-2022

Netwerk

Ariella Aïsha Azoulay

Curator, schrijver, filmmaker, en professor

Dorine van Meel

Kunstenaar, Schrijver

Ibrahim Cissé

Kunstenaar, Onderzoeker