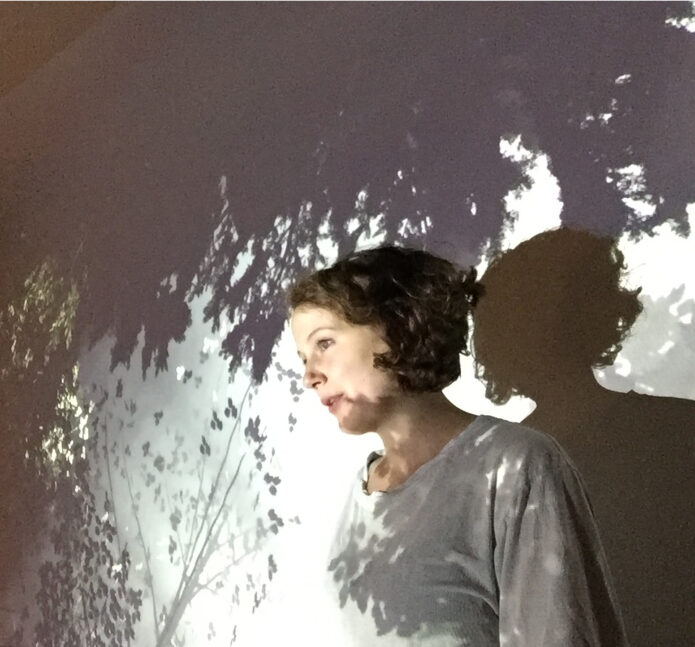

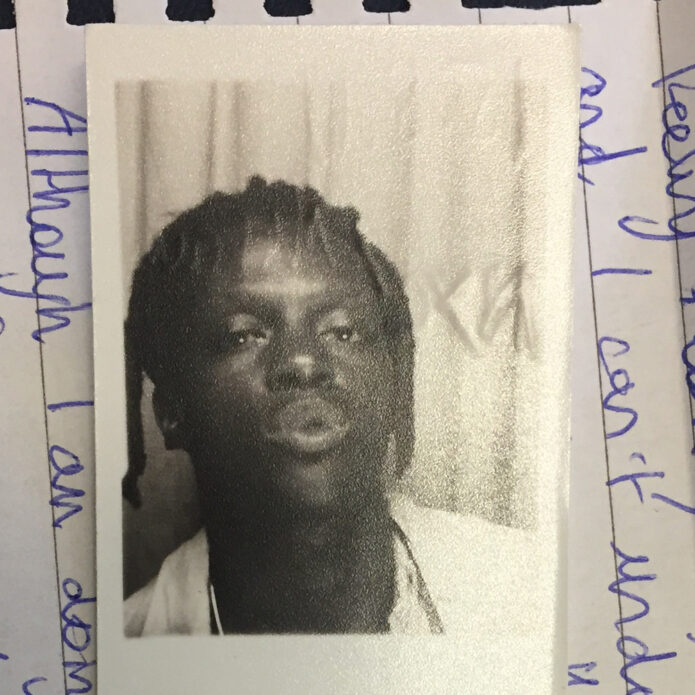

Njabulo Malata presenting for the first workshop 'Against all odds: On compassion and storytelling' at the June 16 Interpretation Centre, Johannesburg. Photo: Zandi Tshabala, 2022.

Njabulo Malata presenting for the first workshop 'Against all odds: On compassion and storytelling' at the June 16 Interpretation Centre, Johannesburg. Photo: Zandi Tshabala, 2022. Report: Decolonial Futures Winter School

In the early months of 2022, Framer Framed hosted the Decolonial Futures Winter School — a chapter of the wider hybrid series which has been ongoing since its commencement in 2020. Resulting from a collaboration between Framer Framed, the Sandberg Instituut, the Rietveld Academie and FUNDA Community College in South Africa, the programme consisted of three constituent parts: The First Term, The Second Term and the Winter School. Read below a report of the Winter School sessions held from February to April 2022.

by Eve Oliver

June 2022

The Winter School consisted of ten workshops split across February and March followed by a symposium, all of which aimed to promote an equal exchange of knowledge and ideas between artists and students to encourage compassion in place of loss and destruction. By utilising compassion, the workshops sought to subvert the power dynamics which characterise the colonial world, encouraging artists and makers to exchange words and feelings of solidarity, equity and kindness to aid knowledge distribution. Hence, the aim was not to follow a strict curriculum, but rather to encourage a new way of thinking and educating to facilitate compassion in educational settings.

Creating Space for a Hundred Flowers to Bloom: The First Series of the Winter School

The Winter School commenced on the 21st of February with a workshop called Against all odds: On compassion and storytelling; led by Samboleap Tol and Njabulo Malata. Based in the Netherlands and South Africa, the pair encouraged the open sharing of stories and music to explore post-colonial lives in the diaspora. To begin, Samboleap shared her background through the medium of storytelling. Speaking in both prose and poetry, she explored how it felt to be a child of Cambodian refugees, and how this encouraged her to turn to art for her own refuge. After speaking openly about her background, the attendees were asked to share meaningful images and music with one other person —an exercise designed to elicit compassion and empathy between people, between artists and between continents. After this safe space was established, Njabulo shared songs which exemplified the premise of a decolonial future, and opened up the platform for attendees to share their thoughts about each piece of music. To convey the importance of lyricism in music, the first song shared was “Amakhamandela” by Letta Mbulu. As the workshop took place in English, the listeners were asked to consider how lyricism transcends language and how sound and rhythm can converge to communicate a message. In this case, Letta fled apartheid South Africa to the US to continue producing music, reminding us that our musical freedom is precarious, as colonialism underpins the world’s structures. Later, Nbulo asked attendees to consider how music influences who they are daily, contending that influence is interracial and is a powerful medium for cohesion in a post-colonial world. Damien Marley’s performance of “Slave Mill” opened up a discussion on censorship within music, as the group grappled with what it truly means to foster a decolonial approach in this area. Where is censorship necessary? Will decolonial education preclude the need for censorship?

The second workshop, The Music of Our Borrowed Time, took place on the 24th of February and explored the concept of what decolonising music means in a commercialised world. Mabeleng Moholo began the session by performing an improvisational curation of music, sound and feeling. He used alternative instruments in a symbolic rejection of popularised ones, to convey how to decolonise music is to deviate from the hegemonic realm of popular culture. Instead, Mabeleng argued that music should be an expression of a visceral reality whereby the consumer is exposed to the creator’s engagement with the medium, which is often missing from commercialised music. Hence, Dusimsani explained that our original sound as human beings could not remain colonised by the elitism of commercial sound. The establishment of this concept facilitated the rest of the session, as Elijah invited each attendee to consider how individualistic their discipline is and how they can adopt a decolonial practice by looking towards community involvement, as music is “who we share it with”. Participants shared links to music which represented their localities, but were also encouraged to choose abstract works to adopt Malebeng’s approach to music. It is such careful, tender moments of open sharing which constitute decolonial practice. Duisimsani then shared knowledge on the effect music has on the molecular structures of water. The interpretation of humans as water-based beings elevates the power of this concept, as our molecular structures shift and vibrate in synchrony with the music we listen to. Thus, if we actively acknowledge the power that music and lyricism have on our psyche, seeking authenticity rather than imitation, we can use music as a force in a decolonial agenda.

We invite you to listen to our workshop playlist and reflect on the themes touched upon in The Music of Our Borrowed Time:

Letta Mbulu – Amakhamandela

Damien Marley – Slave Mill

A Perfect Circle – The Noose

LDF – Indigenous

Music by Mabeleng Moholo

Music by Elijah Maja

Masaru Emoto – Water Experiments

Creating Space for One Hundred Flowers to Bloom was concluded on the 25th of February by The One Policy Project, which focussed on the process of policy making in the arts. Artist and curator Simangaliso Sibiya started the session by proposing the policy of ‘bringing back cousins’ in the artistic sphere, which asks artists to unite as a community to infiltrate museums with a decolonial agenda. As such, this approach is community-based, and sees change as reliant on collectivity between artists rather than individual efforts. The term cousins thus refers to a community of brothers and sisters focussed on decolonial projects. A set of equations constituting the broader ‘Kousin Policy’ were drawn up and presented by Sibiya. This policy is made up of three main formulas, the first being ‘Decolonising the Mind’ (R = F x D², or Reflection equals First Exile times Duality squared), which aids the decolonisation of institutions and individuals through describing the process in simplified, digestible terms. Reflection refers to the ultimate aim: decolonising the mind in its entirety. The First Exile, by contrast, is an all-encompassing term relating to understanding how the human separation from life and sources happened under colonialism. If we multiply this by Duality, a term referring an equal exchange of ideas to aid indigenous perspectives, we arrive at a point of reflection whereby we can discern certain institutional and individualistic behaviours, their causes and how we can decolonise them. Sibiya condensed this down into the following provocation: “by thinking deeply about the separation of sources of life from individuals and institutions and the never-ending dialogue between modernity and history, we can better understand the mind of an institution and how to decolonise it through policy implementation.”

The second formula, named ‘Double Consciousness’ (R = P x C² or Rethinking equals Proverbs times Concepts squared), aimed to give belonging and agency to colonised individuals, who are neither individuals nor in communities, neither European nor African. The use of proverbs as a means of self-understanding leads to a conceptual understanding of one’s place in the world, meaning one ends in a state of rethinking. For Westerners, acknowledging our implication in colonialism allows us to recognise how the ruptures of history have caused our own mental hierarchies related to knowledge systems. Thirdly, the ‘Duality Formula’ (R = M x I² or Reimagine equals methodology times Intellect squared) relates to the indigenous and colonial body of rules deployed and the ability we have in recognising the preoccupation of the latter in the world today. It recommends pursuing critical intellectualism to reimagine the dominating methodology in the arts. In relation to this, a participant asked about our present conditions in the cultural sphere, including how a space would look if we applied these formulas and what defines a space of joy, or of safety, in the decolonial context. Sibiya explained that museums are traditionally glorified containers of stolen objects and problematic art – and the objective is to replace such objects with concepts and knowledge which give humans the agency improve themselves and society. An intergenerational approach to knowledge transmission whereby all ages engage in open dialogues is one way to both democratise and decolonise minds and institutions alike. Ibrahim Cissé highlighted that there is a dichotomy between what art is and what colonialism considers art to be. These formulas are a way of recalibrating fixed narratives, making space for grassroots and indigenous art to flourish. To continue with our present societal schemas and is to condone colonial paradigms of thought.

The second half of the workshop asked participants to apply their learnings to an institution of their choice. One participant suggested that there is often a gap between the institutional voice and the voices of disadvantaged individuals, using the Johannesburg Art Gallery as an example. To circumvent this, we must merge the outside with institutional environments, to ensure museum and gallery spaces truly reflect the society in which they function. Hence, filling spaces with Western ideas and colonial remnants enforces a certain distance between the institution and the individual – Sibiya’s formulas function as a way to subvert this distance and indigenise the institutional voice.

The Womb Republic – How to Rebirth: The Second Series of the Winter School

Bukhosi Nyathi and Lorén Elhili co-hosted the workshop on Tuesday the 22nd of March. Speculative Currencie(s) for mapping African futurities / Place and the dissolving of borders focussed on remapping and redrawing borders in the context of diasporas and monetary economies. To begin the session, Elhili described her current project – Al Mahal – which explores the history, function and placement of minoritarian-owned shops in London. Having grown up in Morocco and London respectively, she sees such shops as places to establish communities, deviating from commercial shops which function only as places to consume. Instead, Moroccan-owned shops in London become sources of comfort in the context of displacement, acting as an ‘informal embassy’ for members of the Moroccan diaspora. Her project involves placing pieces of art within these shops to immerse the communities in her interpretation of immigration, settlement, and integration as a Moroccan minoritarian. In doing so, she questions why many minoritarians turn to domestic shops as a career. She interprets the choice as reactionary to the hostile living and working conditions forced upon Moroccans when they arrived in the UK in the 1960s and 1970s.

In grappling with her own experience of exile, diaspora and transit, Yasmine Benabdallah explores the history, archives and memory of Morocco through the medium of documentary. “Visions of a dreamt sunset” shows distorted images of film and archives produced under British colonial rule of Morocco juxtaposed against the tranquility of Tangier’s landscape. Storytelling and creative writing act as important mediums for individuals in diasporic communities, as they facilitate exploration of personal ruptures, scars and traumas caused by colonialism and exilic migration. Certain discoveries can be made through channelling creative impulses, including awareness of what it means to be a minority in colonising countries. For example, upon arriving back to Tangier to explore her heritage for “Visions of a dreamt sunset”, Benabdallah was struck by her sense of alienation in the city, evidencing that ‘home’ and ‘heritage’ are precarious constructs. She noted “the silence and softness of Tangier’s landscape only make the colonial echoes louder”. Accordingly, Elhili asked participants to consider places of ‘inbetweenness’ they had experienced, where borders are blurred and geography subverted. They were invited to translate such thoughts into a piece of creative writing, after which participants from both Soweto and Amsterdam shared their outputs. Spaces where one feels neither here nor there, present nor vacant, at home nor away were distinguished, such as periods of trauma, displacement and community building following migration. By sharing such stories of ‘inbetweenness’, the colonisers and the colonised can forge new levels of understanding pertaining to what it means to be displaced, and how empathy can be a powerful agent of change-making in decolonial projects. “It is about searching for colonial systems and traumas within myself – whether related to money, fashion, food or language – recognising them, and reckoning with their intangibility.”

The second half of the workshop was led by Bukhosi Nyathi, who explored decoloniality through the lens of economics and monetary commerce in Africa. The economic fractures imposed by colonialism infiltrated many levels of society, including coins and economic systems set up by pre-colonial governments. Our current geopolitical systems are entrenched in colonial capitalism, perpetuating and sponsoring oppressive financial structures which see wealth from African sources such as minerals, concentrated in the West rather than in their original contexts. Nyathi then proposed an alternative economic framework for the countries of Africa, wherein the ‘fatherlands’ would be interconnected in a financial network of trade and commerce called ‘Ntu’, independent from the Global North. Soweto’s members asked those in Amsterdam how Westerners can be allies to this vision. In response, one participant clarified that it is exactly such moments of cultural exchange between heterogenous artists, workers and makers which will lay the foundations for a better understanding of what it means to be an ally of decolonial projects.

On Wednesday the 23rd of March, a workshop named Action – Reaction, The Stopwatch Edition saw decolonial education move from the textual dimension to the creative. Marcel van den Berg ran the first half of the workshop, which focussed on cutting ties with our creative constraints and boundaries by producing art in a context wherein our ability to think and critique our work was removed. In intervals ranging from 10 minutes to 10 seconds, Berg asked participants to draw, paint, sketch and colour. By reducing the time and diminishing our ability to critique ourselves, the art became more instinctual and impulsive, deviating from the propagation and appropriation of art which happens when time is limitless and resources are plentiful. The intervals were matched with different pieces of music, encouraging divergent creative responses and art which reflects musicality as a source. In doing so, this exercise is an important facet of decolonial education, as it is prototypical of the changes artists, creators and makers need to make to their creative thinking and production, which for many is grounded in the colonial ideals permeating society today.

To follow this, the workshop shifted to a more regimented learning session, whereby Kamogelo Matlawe shared his expertise on animation. Kamogelo took participants through the steps which lead to character design. Character designs typically consist of a main character, a villain, accomplices, neutral protagonists and a set. After following his example, volunteers pitched such designs and concepts to the wider group, which was followed by a comedic rating by Kamogelo, whereby he assigned the design to a particular television channel. The exercise exemplified the how digital technology can be a platform on which knowledge exchange can take place, to encourage co-creation, intercontinentalism and diversity in cultural projects.

On Friday the 26th of March, An exploration of African futurisms through sound, ritual and moving image considered the way dialogue can transcend and transgress borders and the concept of nation states. Trevour Mtimkhulu, multi-disciplinary and self-taught practicing artist, began portraying this concept by performing a birth ritual, which followed the creationist view of a child’s journey from conception, to walking and finally to enlightenment. The performance featured a backdrop depicting African spirituality, in which there is no inequality, deviating from the hegemonic hierarchies imposed by Western ideals. He explains that women, before the colonial influx, were powerful interpreters of cosmic language, which gave them the power to detect water movements within the earth. By recognising the power of women in African spirituality, the floor opened up to include discussions on the oppression of women in the wider context, including parallels between the experiences of white women and black women in the colonial context. Jama pointed out that it was often women who formed relationships between the oppressors and the oppressed, an important detail of social history when recognising the protagonists involved in bridging the colonial gap. Considering the intangibility of spiritualism and ritualism, the audience were invited to ask questions to Jama, the first asking him to expand on the relationship between the foetus and the womb, and women and the cosmos. Regarding a baby’s connection with the cosmic language of femininity, the amniotic fluid registers sound waves, it encodes memories, and it enshrines the baby in the mother’s womb. When the mother talks, the baby can hear. Nurturing such rituals translates to the development of cultural identities, as rituals permeate all cultures but in different forms. The participants were then tasked with creating an ancient or indigenous writing symbol which reflects their pasts. After creating their own writing symbols, the participants in both Amsterdam and Soweto shared their creations in an open dialogue which encouraged the sharing of family histories, rituals and spiritualities between two continents.

Artist and writer Asmaa Jama, in collaboration with costume designer and artist Gouled Ahmed, continued with the second half of the workshop, which focussed on various minorities being both invisible and hyper-visible in space. Their joint project, “Before we disappear”, aims to give space to those who feel perpetually seen within the societies they inhabit. The multiple-choice online experience allows those who identify as minorities to navigate a safe space. If the partakers identify as ‘invisible’ in society, they are not allowed to continue with the experiment. To expand on this, Jama led an activity whereby participants were encouraged to engage in creative writing, considering notions of new worlds and global revolution. Each participant’s story began with ‘After the old world ended, the new world began with a…’. Alternative pasts and futures were shared, some of serendipity, others of dystopia, with mutualities of hope for rebirth, peace and justice. In their artistic collaboration, Ahmed matches Jama’s proposed narratives with visual representations of decolonial exploration. As such, they compiled a montage of photographs which explored different photographic and cultural dimensions, such as postures, locations and epochs. Drawing from this example, the participants matched their stories with images which portrayed their narratives to encourage synchrony between visual and textual storytelling. The final dimension of the free-writing exercise focussed on adding sound to the textual and photographic renderings of new worlds. In this way, we were able to conceive, see and hear each other’s ideas about alternative worlds and brighter futures.

Decolonial Futures Symposium: The Final Chapter of the Winter School

The Decolonial Futures Winter School concluded on 3 April with a symposium which comprehensively focussed on the themes explored during the previous workshops. A series of lectures, poetry, performances and discussions explored decolonisation through the lens of Poku Laenui’s observations, which sees decolonisation as requiring not only a reevaluation of political, social, economic and judicial structures, but also as a development of new structures which house the values and aspirations of colonised people. We posed questions on how we should mourn the past, how it should be remembered, how we can imagine alternative futures and how we can commit to action.

A number of familiar faces from the series shared poetry during the symposium. Focussing on how a decolonised future would look and function, one poet saw community and togetherness as an answer to the individualism which permeates colonial societies. Reminiscing the generosity and kindness in his childhood, he explored the loss of community, the convergence of humanity and the power of listening in decolonial projects. As such, the reciters recognised poetry as a powerful tool to dismantle and criticise political systems, as mobilising language as an agent of change challenges us to scrutinise the words we use and encourages us to recognise the political motives certain dialogues have. With poetry facilitating the establishment of a decolonial language, we can attempt to grapple with more hegemonic structures with this language as a starting point.

The symposium then welcomed activist, educator and organiser Zama Mthunzi as a keynote speaker, who shared his experiences in post-apartheid justice movements. To begin, Mthunzi asked the audience to consider what decolonisation means to them personally. Thought-provoking answers emerged, such as “decolonisation means liberation from the past in the present, putting light onto darkness and rekindling humans.” It means “regenerating communities, dismantling the privacy of power, not just a hashtag or a mental process but land retribution.” It requires the “undoing of colonial systematic realities and seeing oneself as occupying a stake in a decolonial future.” Such perspectives hold theory and practice as two separate entities with a causal relationship. Mthunzi added that theoretically speaking, to truly make sense of decolonisation, we must first consult its root, that being colonisation. The historical realities of colonisation saw the colonisers loot, rob, rape, dehumanise, wring-out and murder the colonised people, under theories and political systems which legitimised such crimes. Hence, practically speaking, one concrete action we can enact to begin to reconcile such crimes is to repatriate the lands back to their rightful owners. “For a colonised people the most essential value, because the most concrete, is the land which will bring them bread and, above all, dignity.” Secondly, Mthunzi asked that we do not shy away from the complexity of decolonisation, adding that it is not solely a process of indigenising and romanticising the periods before colonisation. Instead, it is a process of rigorously criticising the current world, without fear of antagonism and conflict with the prevailing powers. It will take a fusion of voices, pluralism and solidarity to pull down and rebuild colonial discourses, structures and systems. To that end, Mthunzi distinguished a theoretical framework from which we can practice decolonial projects in art, education and beyond.

To follow, a series of performances took place which exemplified and explored the introspection and abstraction of decolonial art. Mediums of knitting, poetry, song and lyricism were deployed to communicate personal stories of belonging and loss, of movement and statism, and of memories and futurity. With the timely presence of the war in Ukraine, considerations of modern Russian colonialism were shared from both sides of the conflict. The intractability of invasion and its toll on personal identities were connected to the themes of denial, shame, dreaming, mourning and taking action.

Subsequently, the reflections shifted to the personal story and teaching of keynote speaker François Vergès, whose experience growing up in Algeria has informed her work and revolutionary thinking on decolonial feminism. Being immersed in the French colonial context, Vergès was taught in school that Algeria’s history and future were exclusively French. Hence, her early knowledge on the crimes of French colonialism came not from societal education, but rather from a heterogenous network including her parents and various activists. Her recognition of ‘the state of permanent war’ – a term encompassing the presence of colonial ruptures and struggles across the world today – has highlighted the need for the protection of women, children and ethnic minorities – those constituting the most vulnerable strata in society. With capitalism and colonialism being two sides of the same coin, both are causal and symptomatic of extreme violence. Vergès sees the explanation of this violent duality to not be derivative from men and male dominance alone, but rather from a vast history of white supremacy, in which men were taught that the capacity to murder and inflict violence translates to power. Clarifying the sources of colonial violence as multi-faceted and not over-emphasising one cause is an important factor of change-making, as it allows us to recognise the scope of the issue. She also considers a new order in which decolonial projects flourish and individuals repair, reeducate and start life anew outside the violence and precariousness of capitalism. Such a system would require anti-sexist, anti-racist and anti-colonial education within new shared communities, to aid the process of transformative justice and to unearth a world characterised by equity and humanitarianism.

As the day drew to an end, a final poem reminded each of us to accept the love of others into our hearts – if decolonisation is the destination, then compassion is the road on which we travel. To that end, the Decolonial Futures Winter School concluded. With thanks to Framer Framed, the Sandberg Instituut, the Rietveld Academie and FUNDA Community College in South Africa, for uniting two continents in their collective journeys towards a fairer future with art as the agent.

Action Research / Community & Learning / Diaspora / Shared Heritage / Colonial history / South Africa /

Agenda

Symposium: Decolonial Futures

The final program of the cultural exchange programme with Funda Community College, Soweto, South Africa

Decolonial Futures Workshop Series: The Womb Republic - How to Rebirth

A cultural exchange programme with Funda Community College, Soweto, South Africa

Decolonial Futures Winter School: Creating Space for a Hundred Flowers to Bloom

A cultural exchange programme with Funda Community College, Soweto, South Africa

Network

Lorén Elhili

Curator

Bukhosi Mzikayise Nyathi

Artist

Dumisani Radebe

Photographer, Musician

Njabulo Malata

Writer, Performer

Samboleap Tol

Artist

Simangaliso Sibiya

Artist, curator and educator

Phumzile Nombuso Twala

Writer, Educator

Dorine van Meel

Artist, Writer, Educator

Ibrahim Cissé

Artist, Researcher and Educator

Evie Evans

Exhibition Administrator

Magazine

Report: Decolonial Futures with Aditi Jaganathan