The climate crisis is a colonial crisis - by Roos van der Lint

Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal challenged the Dutch state – and three multinationals with Dutch roots – in their own climate tribunal.

Roos van der Lint

De Groene Amsterdammer, no. 47, 24 November 2021

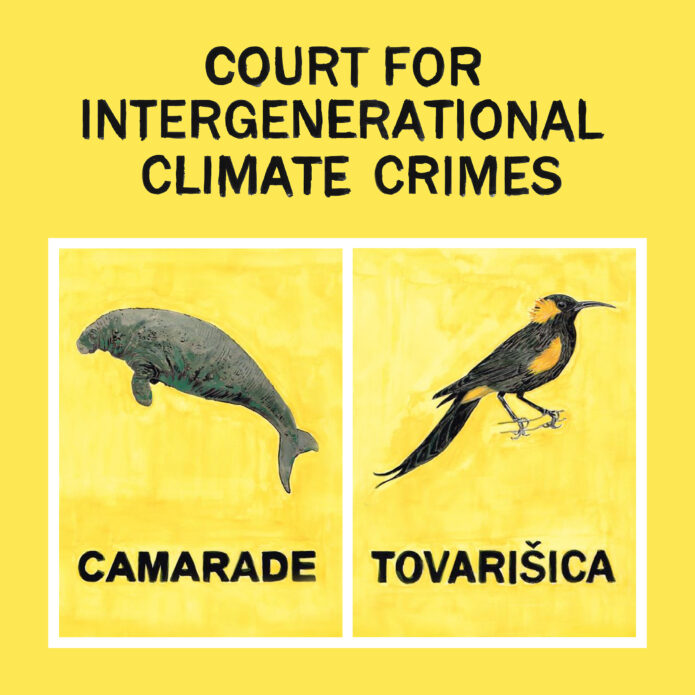

The Saint Helena earwig, last spotted in 1967, the blue antelope, last seen in 1799 or 1800, the Tasmanian marsupial wolf, not seen since 1933 and the Alagoas beaked peacock, disappeared from sight since 1988: they are all present in Framer Framed, the art space in Amsterdam East. Together with over sixty other extinct animal and plant species, they populate the court that has been erected there, the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), a project by artist Jonas Staal and academic, writer, lawyer and activist Radha D’Souza from India.

The animals are painted on boards and the plants woven into textiles, all attached to poles that hold the memory of their existence high up in the air. They are our ‘comrades’, as can be read under their image in dozens of languages. ‘Comrade’ is written under the alburnus akili, a ray-finned fish from the family of actual carp, ‘Kamrat’ in Turkish and Azerbaijani under the Mauke starling, ‘Hoa’ in Maori under the cyrtandra waiolani, a plant that has not been found in the wild since 1943.

Together, they form the audience, the witnesses and the burden of proof of the cases that are brought before this court. They became extinct as a result of ‘intergenerational climate crimes’, the cause of their extinction can be traced back to the colonial era or the global industrialisation that followed. And no one has yet been convicted of these crimes, or even called to account for them.

Now that is about to change. In the four days leading up to the Glasgow climate summit in late October, the CICC came alive with Framer Framed hearings that called a spade a spade. The first case was against the Dutch state, indicted under Article S.3 of the Intergenerational Climate Crimes Act, from the pen of D’Souza, for crimes committed against ‘comrades, past, present and future’ in Bolivia, Peru and Mongolia. The charge specifically concerned the signing of bilateral trade treaties with these countries, with which the Netherlands was guilty of creating a legal framework that served to enrich companies and the state itself. Inhabitants of the Cochabamba region in Bolivia, Amazonia in Peru and the Godi Desert in Mongolia were deceived while polluting and destructive industries were given free rein, resulting in ecological disaster.

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021-2022). Foto: © Ruben Hamelink

During the hearings, cushions were placed at the foot of every extinct animal and plant in the CICC for the public, who also acted as jury, to be seated. The judges, too, each had a comrade by their side, an ammonite, a subclass of squid that disappeared from the globe during the fifth mass extinction. The fossils assisted the judges at the moment of the sixth mass extinction.

Although they developed their own court of law, the law, according to Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, is not necessarily the way out of the climate crisis. The legal system itself is an essential part of the problem.

On the day after the final hearing of the CICC, the first day of the conference in Glasgow, D’Souza and Staal appear together in a video interview. Their collaboration was not an obvious one. Staal a committed artist from the Netherlands, became known with De Geert Wilders Werken (2005-2008) (De Geert Wilders Works): memorials in public space showing the politician as a living martyr. Since then, he has organised meetings under the title of New World Summit (2012-present), a series of alternative parliaments where stateless and blacklisted organisations were invited to speak. He has also been active in Rojava, the autonomous region of the Kurdish revolutionary movement in northern Syria.

D’Souza, amongst others, has worked at the Bombay High Court, taught at universities in New Zealand and is currently Professor of International Law, Development and Conflict Studies at the University of Westminster in London. As an activist, she was committed to movements fighting for social justice. They met at a conference in Hamburg in solidarity with the Kurdish movement and saw the connection between their fields of work, between progressive art and social activism, as a shared ground for collective action. D’Souza repeatedly chaired Staal’s New World Summit.

D’Souza’s suspicion of the legal system dates back to her time as a lawyer in India, practising on behalf of minorities and marginalised groups. ‘The longer I worked as a legal practitioner and activist, the more it dawned on me that there were fundamental problems with the idea of “rights”.’ It is the central idea in her book What’s Wrong with Rights? (2018) and inspiration for the collaboration with Staal in the form of the CICC: human rights and economic rights or property rights are legally strictly separated, but in reality intimately linked. Economic rights, she says, after the founding of the United Nations in 1945, were given to organisations such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Health Organisation (WHO), and what they decided was no longer in the hands of the people who had to live under them.

The emphasis on a legal human rights framework became a means to enforce other things: neoliberal governance on a global scale. ‘When the World Bank started talking about human rights in the 1990s I thought: wait a minute, why on earth does the World Bank want human rights? The Bank’s mandate is to promote financial markets, what are they supposed to do with human rights?’

D’Souza saw many good analyses by lawyers and activists of the problems people faced, but they got stuck in finding a solution. ‘We are in a deadlock because we think that human rights are the solution. And then the World Bank says: yes, of course, human rights, we will finance them, on our terms. Human rights are given with one hand, economic rights are taken away with the other. As if human rights can exist without people having to earn a living.’

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021-2022). Foto: © Ruben Hamelink

No, in her book she does not directly link these thoughts to climate. But her critique is directly transferable. Staal reads a passage: ‘Land is essentially a relationship. Land is not a thing, it is a bond that connects people to nature and to each other. Land is a glue that holds people and nature together in one place.’ That observation touched Staal. It is not about rights, it is not about ownership, it is about interdependence. If you violate the so-called rights of a river, you also violate the lives of all the people, animals and plants that live on that river. And of all future plants and animals that would or could have lived in dependence on that river. So how can you isolate rights as individual property without relating them to the interdependence that is thereby damaged?’

D’Souza adds: ‘Land has become property and people have become labour. That is what the separation of nature and people does, and then you can sell labour on the labour market and land on the land market. The land that you stand on and the work that people have always done are transformed into commodities, and that happens through the intervention of law and legal systems.’ Staal explains how the first waves of animal and plant extinctions and our legal system go back to the same moment. The climate crisis is a colonial crisis. And the law was a necessary tool to legitimise looting and claim rights over others, to transform living worlds into property.

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021-2022), Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: © Ruben Hamelink

The idea of interconnection is central to the CICC. This court looks beyond the interests of man, consistently speaks of people, non-people, more-than-people and other-than-people. It weighs up the interests of everything and everyone from the present, past and future, the timeframe extending across generations. In the middle of the court is an intriguing basin with a layer of refined oil and a fossil in the middle. It is like a black hole into which everything converges. As Staal says: ‘The fossil in the fossil fuel represents the absurd confrontation between a time span of hundreds of millions of years of accumulated remains of plants and animals in the oil that racial capitalism (after the term ‘racial capitalism’ by Françoise Vergès – rvdl) burns into the present, thus denying the possibility of a future.’

We are trapped in the present as a result of past choices and this results in a life that is necessarily full of contradictions, says D’Souza. If you have a car, for example, you have to fill up your tank at a petrol station owned by an oil company. Maybe not at Shell, but if you don’t get ahead, you can’t even fight an oil company.’ You could challenge her by asking: how can you be critical of the legal system and yet fight lawsuits? ‘Because then you accept the whole legal system that made Shell, for instance, possible in the first place. But if you don’t file the lawsuit, you will be overthrown anyway. Then Shell will continue to do what Shell does.’

The society into which you are born is a fact that you cannot avoid, but aspects of it we can certainly resist. ‘I was born into a patriarchal society, but that doesn’t mean I don’t love my father. That too is a contradiction.’ Just like the fact that the CICC sues the Dutch state, but is also partly subsidised by it? ‘Well, my father sent me to university. He wanted me to be a lawyer, not an activist, but he paid my tuition fees!’

On the next three hearing days, the Dutch State was also summoned before the CICC, along with Unilever, ING and Airbus, respectively. Staal acted as clerk of the court, D’Souza as presiding judge of four in total. The charges spoke the truth, as did the evidence. A prosecutor in the person of a journalist, researcher or activist first presented the case, after which witnesses gave evidence, sometimes in the room, sometimes by video link. In the case against Unilever and the Dutch state – indicted for, among other things, the thermometer factory in Kodaikanal, India, where in some places mercury levels still reach fifty thousand times the maximum permitted amount – poignant testimonies came from India, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the case against Airbus, suspected of both manufacturing and supplying weapons and destroying entire ecosystems under the protection of the Dutch state, impressive testimony came live from Yemen. Empathy was evident in the questions and the concluding thoughts of the judges. In the four days it was in operation, the CICC made an unprecedented powerful impression.

In each case, D’Souza looked around the room at some point and invited people to speak on behalf of the defendants, all of whom had been sent a summons by the CICC. Nobody spoke. At the end of the day, the jury was made aware of the important task of weighing interests, many of them as residents of the Dutch state that was on trial on so many issues. Each case ended with a clear verdict: guilty.

Yet, that moment did not feel like a victory. The powerlessness had been demonstrated, the disparity between multinationals acting as ‘legal entities’ and the lives of real people. At the conference in Glasgow, Unilever was prominently mentioned as a ‘principal partner’. Where is the justice, where is the justice to be found? At one of the hearings, D’Souza quoted Gandhi: ‘If you want real equality, you have to have unequal laws. If the laws are equal, you get inequality in reality’.

On the last day of the CICC, someone suddenly raised his hand and spoke in defence of Airbus. The man disregarded the status of the court in an art space. ‘You are a very small number to have an impact on us. You can circulate these facts in your closed circle.’ That, of course, was the arts’ weak spot and, in a sense, also the elephant in the room: what did this climate court actually mean?

For Staal, this intervention was a welcome opportunity to address the issue. In his closing words, clerk Staal addressed the jury as an artist: ‘As artists and cultural workers, we do not have executive power in the way that the political class has. But we have the power of imagination, and imagination is an essential component of any form of social change. If we cannot imagine what we want, we cannot realise it.’

Staal views artworks as seeds that germinate in time: imaginations are planted. ‘They may not manifest themselves immediately, but once they are planted, it is very difficult to undo. ’He emphasises that the CICC does not stand alone, but needs to be seen in connection with the work of, for example, Extinction Rebellion, the Urgenda lawsuit and progressive political parties. ‘For me, that is the only way to appreciate such a work of art, in relation to the broader movements fighting for the possibility of social change.’

The physical experience of the CICC was also important to Staal and de D’Souza. That people could step into a space that they might have longed for, but never thought possible. Staal: ‘We know that The International Climate Crimes Act that Radha wrote is not currently the law of the land, but together, we have embodied and experienced the possibility. You plant a seed as deep as possible. And you can’t say the court didn’t exist, it certainly did.’

D’Souza tells about an activist who came to her after a hearing. He has many experiences with court cases and said: ‘Every time I went to court, it felt like theatre. I came to this court and for the first time it felt real.’

D’Souza closed the CICC with an insight from her grandmother: if you trample a worm, it will turn over in an attempt to stay alive. D’Souza in court: ‘Survival does not depend on man-made laws. Every form of life will fight until its last breath. This is the law of life, the law that this court accepts.’

D’Souza calls herself a ‘pathological optimist’, and not without reason. ‘Optimism is rooted in history. Time after time, people have claimed that nothing will change. And every time, something changes.’ She gives an example from her time as a trade union leader: ‘There was a factory in Bombay where we couldn’t get a foothold. We told the workers how they were being exploited but it seemed to fall on deaf ears. Until one day one of them found a cockroach in his food. He went to the manager and said: look, this is what you are giving us to eat. To which the manager said: if you don’t find cockroaches in your food, what are you then going to find? When the man told his colleagues, a strike broke out immediately, one of the longest conflicts in that factory.’

What she means to say is that even a worm turns around, and these are human beings. ‘They will not die quietly because Airbus wants to sell weapons. They may die eventually, but not without a fight. I know I will not go quietly into my grave,’ D’Souza laughs. ’And there are many like me.’

The verdict of the judges is expected in the near future.

This article previously appeared in De Groene Amsterdammer and is reproduced here with permission.

The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes can be visited free of charge until 13 February 2022 at Framer Framed in Amsterdam.

All hearings can be viewed online at: https://vimeo.com/showcase/9091118.

CICC / Ecology / Colonial history /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes

A project by Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal

Network

Radha D'Souza

Writer, academic, lawyer and activist