Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021)

by Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Photo: Ruben Hamelink

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021)

by Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Photo: Ruben Hamelink Report: The CICC, a DIY Court for Climate Crimes

In late October 2021, a spectacle as enlightening as it was confusing took place in the Framer Framed arts centre building in Amsterdam. Multinationals linked to the Dutch State, and that state itself, stood trial for their ‘intergenerational climate crimes’.

By: Kees Hudig

Published: 7 Februari 2022

The project began on September 24, 2021, when the initiators of the Court for Intergenerational Cliame Crimes (CICC), Framer Framed, Jonas Staal and Radha D’Souza opened the exhibition and deposited both the legal basis and the charges against the four defendants who would later stand trial.

Jonas Staal is a Dutch artist, who had devised the setting of a courtroom to make visible what crimes are currently (and have been in the past and therefore in the future) being committed. Radha D’Souza is an Indian/British lawyer and activist, who published the book ‘What’s Wrong with Rights‘ (Pluto Press, 2018) about the problematic relationship between formal rights and victims who are condemned to use them to actually get due justice. The book is central to the project.

Radha D’Souza, with a team from Framer Framed (disclaimer by this writer: I was also involved), had worked out three very physical cases per ‘case’ that would have to support the accusation. And she led the court, assisted by three other ‘judges’: Sharon H. Venne, Nicholas Hildyard and Rasigan Maharajh.

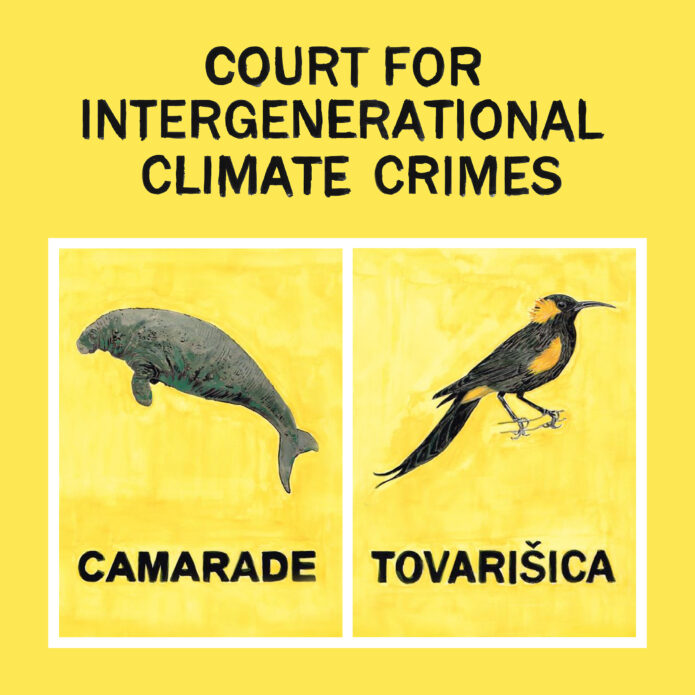

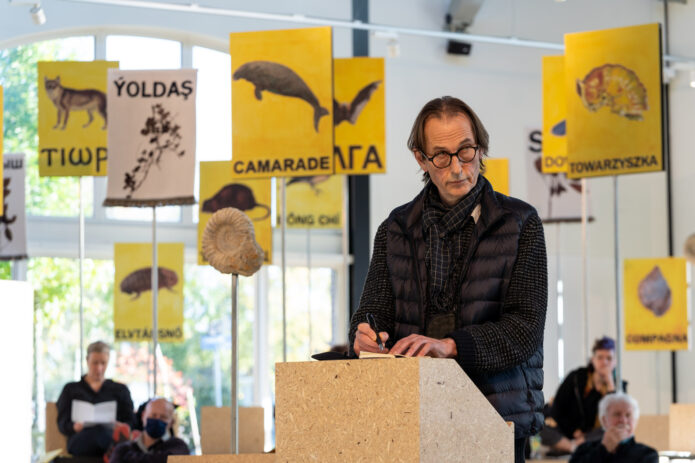

The space where these proceedings were taking place, and where the public could attend as a jury, was hosting an exhibition of paintings of extinct animals and plants. They were the “comrades” who could no longer defend themselves. Not only because they were extinct, but also because they are not human beings and therefore have no place in the administration of justice. Between them were large casts of ammonites, and in the middle of the room was a silent oil tank. The organic basis of the fossil fuels that are now causing the climate disaster. But also the tangible relationship between us, and our activities now, and the history of the earth and what was and is being done with it. The exhibition lasted until February 12, 2022.

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2012-2022) by Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal. Photo: Ruben Hamelink. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam

Four days, four charges

During four days—from October 28 to 31—the four cases were litigated extensively. On the first day, the Dutch State itself was the defendant, followed by Unilever, ING Bank and Airbus.

The form always remained the same. Jonas Staal, as ‘clerk’, read the accusation. Then there was an introductory story about the accused by an expert researcher, activist or journalist. This was followed by three ‘cases’, all presented by people who were involved locally. The judges asked questions to those witnesses, and at the end, each of the four judges gave a sort of philosophical conclusion about the day’s trial. But also at the end, the accused were called upon by Radha D’Souza to defend themselves. All four perpetrators had been summoned in advance and had been sent the accusation, mostly in the form of CEOs or government officials living in the Netherlands. They didn’t show up, but it was a poignant moment, as the room sat waiting every time, in suspense to see if anyone would speak up for the defence.

Originally, the plan had been to have all the witnesses come to Amsterdam so that their testimony would be well presented, and they would also be able to participate in the other cases and meet fellow victims. But because of the corona, that become impossible and everything had to go online, which was a true technical tour de force. It was also a request to have each testimony accompanied by a short video to properly portray the issues. In the end, we succeeded in having people testify and answer questions in every case. The official language in all of this was English, except for a few French-speaking people and an indigenous Peruvian. They received a translation through interpreters.

Photo: Ruben Hamelink

The Dutch State

The introduction to the role of the Dutch State in “intergenerational climate crimes” was given by Bart-Jaap Verbeek of the research organisation SOMO. He gave an enlightening overview of the constructions by which the state works to facilitate activities of companies and multinationals elsewhere. The whole structure of bilateral trade and investment treaties and tax agreements makes the Netherlands one of the main countries of establishment for multinationals from all parts of the world. They often do not have any actual activity in the Netherlands itself, but are established here via shell companies to make use of the bilateral treaties and tax facilities. But the entire structure that the Netherlands has rigged up for this purpose is a real edifice, a legal-economic empire.

This was followed by the three cases. The first is narrated by Sukhgerel Dugersuren, from OT Watch in Mongolia and was a dramatic story of mining in a remote, desert-like part of the country. The gigantic Oyu Tolgoi copper mine of the American multinational corporation Rio Tinto is causing enormous damage in the area, which is inhabited by nomadic herdsmen who see nothing of the proceeds in return, which after all disappear via the Netherlands to tax havens.

The second case was a famous historical case, that of the privatisation of drinking water in Cochabamba, Bolivia. The case was highlighted from Cochabamba by Marcela Olivera, of the Blue Planet Project, who herself had played a major role in the protests against that privatisation. When the population revolted en masse and chased the privatised company out of the city, the American company Bechtel sought massive compensation through the Dutch investment treaty with Bolivia. They wanted to be compensated not only for their investment but also for future lost income. This again led to new protests, also in the Netherlands, and finally, Bechtel saw itself forced to ‘settle’ for a symbolic amount. According to Olivera, ‘for the price of a used car’. But meanwhile, the damage was enormous and the water supply is still problematic.

The third case came from Peru, where an Argentine oil company, Pluspetrol, has been drilling and pumping oil, leading to large-scale pollution in the Amazon forest. Nearly 2,000 drilling wells were left without any clean-up. Residents and indigenous organisations have fiercely resisted and demanded that the company clean up its projects, but it eventually declared bankruptcy and left things as they were. The residents’ organisations have even come to the Zuidas in Amsterdam, where Pluspetrol is formally based, to seek redress but have so far received nothing.

You can watch the entire session of more than five hours here on YouTube. On 13 June 2022 the final verdict in the hearing held against the Dutch State in the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC) where presented.

Unilever

On the second day, it was the turn of a multinational that had recently left the Netherlands, but still has all kinds of ties with it. Unilever has been a Dutch-British corporation from the outset and for a long time had a dual-headed legal structure, which was inconvenient in recent times because shareholders had to be served in both countries. Initially, Unilever opted for the Netherlands as its only ‘home country’ but wanted in exchange for the dividend tax to be abolished. When that demand caused a stir, the company opted for London.

The general introduction about Unilever was provided by journalist Daphné Dupont-Nivet, who had written about the company for the magazine Groene Amsterdammer and works for research platform Investico, among others. Daphné outlined the history of the company, which is closely linked to colonial (Belgian) relations, and focused on the company’s activities with palm oil. And about ‘greenwashing’ by the company, which claims to operate sustainably, but is at the same time one of the largest buyers of palm oil in the world.

The first case was a former thermometer factory in India, where Unilever had a subsidiary that made mercury thermometers in Chenay. Nityanand Jayaraman, of Vettiver Koottamaippu explained the consequences of dumping waste from the factory – including whole batches of broken thermometers, in a nature reserve known as a ‘biodiversity hotspot’. And how all demands for compensation and clean-up were in vain.

The second case, the testimony was given by Faith Alubbe, of the Kenya Land Alliance who was the only one of all those witnesses also present in person, involved tea plantations in the Kericho and Bomet region in Kenya. The land for the plantations had been forcibly taken from local residents and the working conditions were correspondingly poor. Subsequently, the cultivation of tea was also extensively mechanized, creating unemployment, and the cultivation involves pollution and pesticide use, with no desire to listen to complaints from local residents.

The third case was, possibly, even more horrific. It concerns the palm oil plantations where Unilever once started in Congo (then owned by the Belgian king). Now, more than a hundred years later, the plantations are still the scene of large-scale human rights abuses. Jean-François Mombia Atuku, of the organization of affected residents RIAO-RDC held a furious speech and told of severe repression against the local population, who had demanded, among other things, that they be given back the land when Unilever wanted to leave there a few years ago. In reality, the plantations, with support from the Dutch ‘development bank’ FMO and others, were handed over to an opaque Canadian investment fund, which allowed the excesses to continue.

Third day: ING Bank

On the third day, it was the turn of the Dutch bank ING to be scrutinised.

Rodrigo Fernandez, from SOMO, gave the introduction and outlined how this bank has an aura of dullness and solidity but is now active in areas that have little to do with it. The bank is certainly not alone. It is a relatively small player in the entire field of financialisation of the economy and ‘infrastructural power’. But since the split-up of ABN-AMRO, it has become the largest in the Netherlands, and the consequences of the activities are no less pernicious.

Testimonials on individual cases were provided by Meiki Paendong of WALHI in West Java where ING is financing a coal-fired power plant, or a second actually which only makes matters worse because the first was already such a disaster. The consequences for people in the area are disastrous, and they want the project to be stopped as soon as possible.

A second testimony came from Cameroon, where ING is involved in oil palm plantations. This time it concerns the Belgian company Socapalm/Socfin and Emmanuel Elong of the organisation SYNAPARCAM showed the consequences; residents no longer have land to cultivate themselves and water and the environment are seriously polluted. They resist and are severely persecuted.

The third testimony came from Brazil where Fabrina Furtado, from the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro had laid out for the audience the role ING and other banks play in large-scale agricultural projects that are disastrous for the forest or swamp/savanna and leave residents powerless. It is a massive project for the production of cheap raw materials for the western economy, and ING is in the middle of it (see images here).

Fourth Day: Airbus

Then came the fourth, concluding day, and it was Airbus’ turn. As far as people know that company, often have the image of an aircraft manufacturer, the European counterpart of Boeing. But the Netherlands-based company does much more, and that remains deliberately hidden because it is involved in weapons, war, and the bombing of civilians.

This day’s introduction was provided by Wendela de Vries, who has been following the company for years for the Foundation Against Arms Trade (Stichting tegen Wapenhandel) and also organises protests at the shareholders’ meeting every year. They are part of an international network against arms companies. Airbus is a veritable hydra with many heads that remain mostly invisible but are partly based in the Netherlands. And it remains fascinating to see how normal it is for such a company to make money from all kinds of wars, including those in Yemen and Libya, about which local witnesses later spoke. The picture becomes even more perverse when it is explained that the company is also heavily represented in border control technology. So, you earn from destroying areas, usually far away from the civilised homeland, and then again from stopping the victims who try to flee the destruction.

In the civilised Netherlands, it is generally forbidden to bomb homes with unarmed families. Nevertheless, it is permitted to produce weapons and accessories and sell them at a profit, which is what happens. Civilians are not allowed to do that, but a company like Airbus exploits the legal constructs that make it possible. Occasionally, after long campaigns by peace movements and human rights groups, international treaties are made to ban certain weapons, or at least to try to regulate them. Those companies are typically closely involved in the process of drawing up restrictive rules and Valentina Azarova of Global Legal Action Network explained how arms companies deal with this and bend the rules to their will, or circumvent them (Image).

Muhammad Al-Kashef, from Watch the Med Defense spoke about the European regime of border surveillance and infrastructure to keep refugees and migrants out, which Airbus is thus ‘creatively thinking’ to help this take place whilst making a good profit from it.

In the last block on Airbus, witnesses came forward, via sometimes laborious internet and with translation, to talk about what actually happens with that weaponry ‘on the ground’:

Karim Salem, from the Cairo Institute for Human Rights Studies, and people from Libya and Yemen who were trying to follow how the wars and interventions there were working out, taking great pains, at the risk of their lives, to keep track of what bombings were taking place, and where the weapons were coming from. This, of course, is a terrible story, one that was literally difficult for those present to digest.

Watch the entire broadcast here.

At the end of each session day, the audience present, as a jury, was already allowed to make the first verdict. In all four cases, there was a solemn “guilty” verdict, by a show of hands. A large majority of the audience, sometimes even unanimously, held that opinion. In one case, one of the audience members stood up for the accused. He made the point that this court was nothing, that all activities were legal under the law, and that no company would care. Again, that was all true…

Going home with the knowledge

After four days of hearing/seeing a lot of disturbing information, and constant ‘direct contact’ with victims of Dutch economic practices, the judges went home with the task of passing judgment later on.

But also the participants and audience went home and have to decide, pass judgment, and above all: find a perspective to deal with this. During the four court sessions, people were often visibly upset. Here and there, some tears were shed in the room at certain testimonies, or someone could no longer remain seated to watch.

The extent to which we were disturbed by the realisation that respectable multinationals are running from the Amsterdam ‘Zuidas’ (the financial district, South Axis) to produce bombs that will later be used to flatten entire families was perhaps the most significant case. But also the other multinationals, from the respectable ING that supplies the national soccer club with shirts, to Unilever, which claims to be so well-disposed towards the sustainable world and the Netherlands with its development aid, and with investment treaties that enable the privatization of water in Uruguay, mining in Mongolia or oil pollution in Peru, are hardly inferior to Airbus.

But what did we experience, in those four days? Was it art show? It all looked beautiful, and the video links were flashy. Or was it journalism, with all those files and economic explanations? Popular science, perhaps, to expose connections that usually remain hidden? Activist? And then why no calls to action? A mixture of all that? Or something entirely new? Or can we, in a very modern way, just figure it out for ourselves?

One of the curious phenomena about the whole project was the rigidly maintained formality of the whole thing. The room did not really look like a courtroom, but it carried a certain solemnity. The language used by the Clerk and Judges was also entirely in accordance with the protocols we are familiar with and the designed legal framework, and the official accusations were drafted in the problematic alienating language that accompanies legal proceedings.

Radha D’Souza, when asked, explained why this pattern was chosen: “Otherwise it wouldn’t be a court, would it?” There are plenty of activist rallies where a particular injustice is exposed and denounced. But this was set up differently. The result was that you might also start thinking differently about the origin of the problem, its deep colonial roots, and the relationship between the “crime” and past and future. And the relationship you and your fellow humans have to it again, up to and including the trilobites of thirty million years ago.

At the same time, Radha remarked, “I have heard from people that for the first time in their lives they really felt that they were involved in this ‘court’ as a participant in the process. You never have that in official law. It happens to you, usually because you are being prosecuted yourself. But this was different, here you could have your share, and you had the feeling that a common interest was being fought for.”

For further questions, we may be able to attend a meeting later this year, when the judges come out with their final judgments. (*) And perhaps that will also be the time and opportunity to think about what we are going to do about it. The question is whether we, and especially those people who now have ING all over them in West Java, or Unilever in Kenya, and certainly Airbus in Yemen, have that much time. We now know what the Dutch Legal Empire looks like and stretches across the world. So now, whether we want to or not, we are complicit…

Continue Reading

You can find more documentation on the exhibition in the Digital Archive: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes.

See for example the catalogue of extinct ‘Comrades’, the animals and plants ‘present’ as witnesses during the hearings.

Read the article The climate crisis is a colonial crisis by Roos van der Lint.

All video recordings can be found here: https://vimeo.com/showcase/9091118

(*) The first meeting for a verdict for the Dutch State took place on June 13th, 2022 in Amsterdam. More info

CICC / Ecology / Extractivism / Art and Activism /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: CICC Seoul - The Law on Trial

A new iteration of the project Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC) at the Oil Tank Culture Park in Seoul, South Korea.

Exhibition: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes

A project by Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal

Agenda

Verdict Presentation: CICC vs. The Dutch State

Presentation of the verdict in the CICC vs. the Dutch State case

Opening: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes

By Josien Pieterse, Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, commissioned by Framer Framed

Network

Sharon H. Venne

Cree historian and writer

Rasigan Maharajh

Activist scholar and scientist

Nicholas Hildyard

Writer and director, The Corner House

Radha D'Souza

Writer, academic, lawyer and activist

Jonas Staal

Artist

Magazine

Errant Journal: A conversation between Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal

"Nature is not an object of property, but subject of rights"

The climate crisis is a colonial crisis - by Roos van der Lint

From the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: The Lives and Deaths of Oil