Kartono Yudhokusumo, 1946

Kartono Yudhokusumo, 1946 Verslag: Modern Indonesian painters in revolution and nation building

Throughout March and April 2017, Framer Framed hosted a series of lectures on the relationship between imperialism, visual arts and literary arts in former Dutch colonies. These lectures were organised with Prof. Dr. Michiel van Kempen, the chair of Dutch-Caribbean Literature of the University of Amsterdam (UvA).

In the lecture of 19th of April, Dr. Michiel van Kempen began by introducing the speaker of this evening, Iwan Sewandono, as an anthropologist and musician. He also outlined the aim of the lecture as placing the developments of modern Indonesian painters within the framework of nation building.

Sewandono began by outlining some developments in Indonesian nationalism. He stated that contrary to common views, he did not believe that it began in the revolutionary years, around 1928, but instead goes back further to about 1860 when the English returned their Indonesian colony to the Dutch. He differentiated between commercial colonization of those particular years, and exploitation colonization that began after 1860. Sewandono believed that post-1860s was a time of exploitation, because the Dutch were poor after the French ruling years and therefore became more exploitative in their colonialism than before. This began a series of violent events and clashes amongst the Indonesian population. Sewandono was quick to remind the audience that in those days these areas were not called Indonesian.

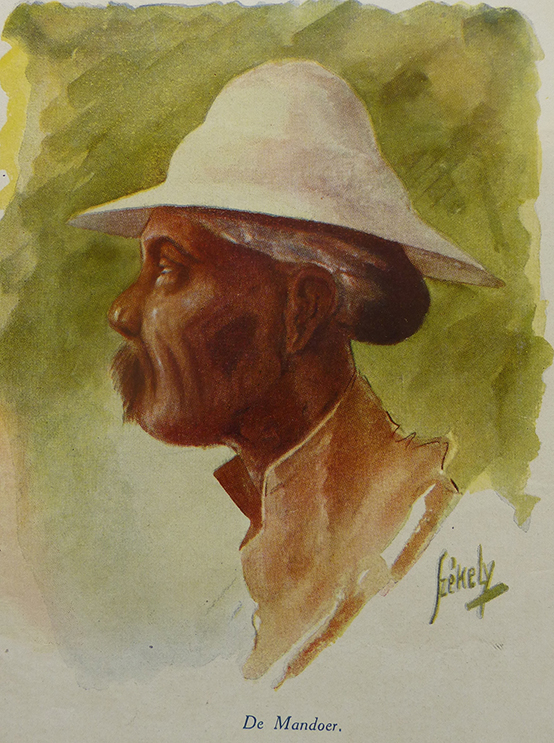

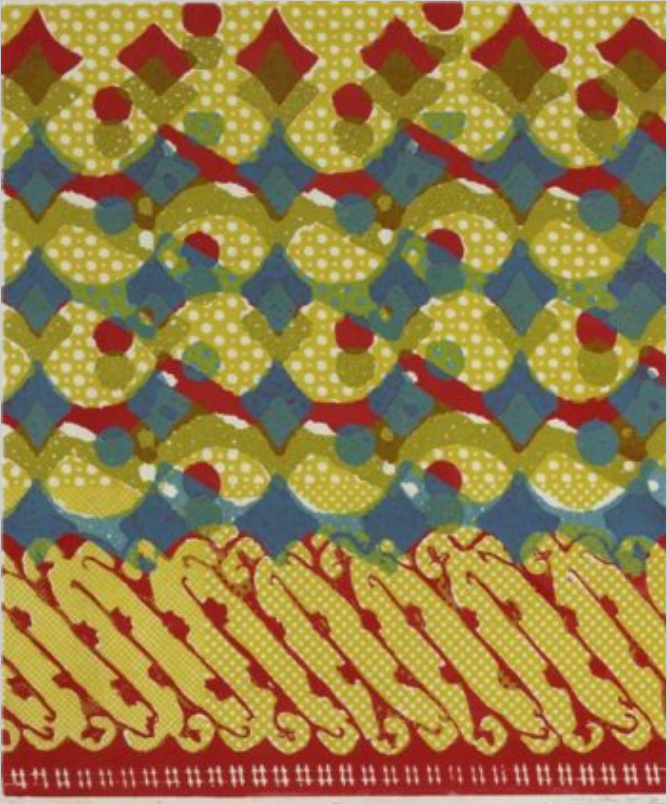

Sewandono then moved on to talk about Indonesian painters between 1935 and 1965, which he called modern painters. He also referred to them as folk painters because they played a crucial role for creating nationalist sentiments, and an identity for a young Indonesian state. He listed some key painters: Widayat, Sudjono and Hendra Gunawan. He showed some images of paintings by Hendra Gunawan depicting fisherman, peasants, prostitutes and other people at the lower levels in colonial hierarchy, and later the hierarchy of an independent Indonesia. He continued by showing the influence of both batik and Japanese painting in some of Widayat’s painting techniques. Sewandono emphasized the importance of Sudjojono, who wrote some expressive essays that formed a framework for Indonesian nationalism amongst painters.

Sewandono also emphasized the significance of kejawan: “you can’t understand Indonesian art if you don’t know about kejawan” – what he explained to be a long history of Javanese soul and culture. Kejawan includes spiritual animism, Buddhism and Hinduism. Sewandono believed this is an important concept to have in mind when exploring Indonesian paintings and their common mythological depictions, sometimes from Hindu epics, like the Mahbharata or Ramayana. He stated that integration has also been one of the big sources of conflict and tension throughout the history of this region; as Indonesia spans a huge geographical space and was divided between different cultural groups: “people couldn’t look much further than their own small kingdoms”. Sewandono argued that Dutch colonialism turned this diverse area into an integrated whole. Mythologies and kejawan were an important part of everyday life and education amongst Indonesian groups during this time. Sewandono then stated that earliest nationalist sentiments can be located in the shift from commercial to exploitative colonization; he linked the emergence of the concept of Indonesia and nationalist identity to worsening conditions under imperialism. Sewandono described this period as one of resistance, and said that Prince Diponegoro is an important figure of this time. Prince Diponegoro organized Indonesian mobility with peasants against the Dutch and Indonesian monarchy of Jakarta, his own family. Sewandono believed that the Java war against the Dutch was an early instance of different groups mobilizing themselves as a whole – as Indonesian.

Sewandono went on to describe the relationship between the Dutch colonials and the Indonesian population after the confrontations of the Java war. He believed that following these war years, there was a period of uneasy cooperation, with the Dutch implementing a new system of exploitation that ended the power of Indonesian nobility and monarchies. This ‘culture system’, as Sewandono called it, or fiscal system, profited the Dutch but also gave different sectors of Indonesian society a stake in the colonial system. Sewandono believed there was a mutual avoidance of violent confrontation from all sides, and so the Dutch instead gave certain privileges to all Indonesians who cooperated with them. This type of exploitation continued until ’71.

Sewandono then outlined some of the processes by which a petit bourgeoisie developed through the integration of Dutch family life in Indonesian areas. He explained how after 1894 there became a new understanding of national identity. Until that year, if you were white and living the colony, you were considered to be white and Dutch. However, later on, Dutch standards of living became more integrated with Indonesian life, and even became goals of Indonesian-identified families to reach. Sewandono used the example of Prince Diponegoro to illustrate this point: Prince Diponegoro studied in Leiden and became part of the Dutch army. With this Dutch education and living style, he returned to his kingdom and implemented the knowledge he had acquired; executing modern governance, irrigation works, forestry works and medical care. One could gather from this point in the lecture that Sewandono was implying that Dutch notions of structures and culture were being incorporated into Indonesian ways of life.

During the development of a kind of petit bourgeoisie, or a so-called “modernized” lifestyle, there was tension with indigenous lifestyles that were considered “uncivilized”. Around that same time, some individuals organized art circles. Sewandono believed the most important of these art circles was found in Batavia. This particular circle would organize international exhibitions and events, including concerts and a museum that still exists today.

During those years, Dutch colonials were trying to cooperate with Indonesian communities, for example, by including Indonesian people as colonial administrators. In that context, Mrs de Loos became a key figure in many art circles. She was married to Walter de Loos, a colonial administrator in Jakarta. Her connection to the colonial administration gave her an influence on painting styles. As her focus was on Dutch audiences, she pushed Indonesian painters to paint either in the beautiful Indies style or a style of Bali – a style closely in cooperation with European painters. The beautiful Indies style is highly romantic, depicting beautiful landscapes and harmonious life. That was her opinion on how the Indonesians should develop themselves as painters.

Mrs de Loos organized that some of the art collection from the first director of the Stedelijk came to her museum in Jakarta. She succeeded at getting a state of the art collection in Indonesia – much better than what you could find in the Netherlands or in Paris. This was very important for the European population. Sewandono emphasized that whilst Mrs de Loos was encouraging of art and painting, she had specific ideas of what Indonesian painters should make. Sewandono said that around 1938, Indonesian painters outsmarted her by creating an exhibition of their work, which even European populations were coming to see. The speaker described these painters as ‘fighting’ their way into highbrow circles. Sewandono depicted the content and subjects of many of these paintings as representing folk identities, like peasants, prostitutes, poor people, typical market scenes and rickshaw drivers. He called this focus nationalist because it depicts scenes of everyday Indonesian life.

Sewandono then referred to Mrs De Loos as the ‘grandmother’ of modern Indonesian art because of her work in creating European-focused art interest and exhibitions in Indonesia. One could argue, then, that the concept of “modern art” is, to a degree, linked to a Western influence. Therefore, the concept can become politically loaded, particularly in nations that are former colonies of Western countries. Sewandono concluded his lecture by stating that Mrs De Loos’ position in Indonesian history is ‘unwanted’, because she was a white European and a member of the colonial elite. From these statements, it may be that Sewando was suggesting that through her assumptions about European and Indonesian painting, Indonesian painters were pushed to develop specific styles and further develop nationalist sentiments.

Report written by Anjali Prashar-Savoie

Indonesië / Gedeeld erfgoed / Koloniale geschiedenis /

Agenda

Lezing: Iwan Sewandono - The outframed framed in: modern Indonesian Painters

Lezing door Iwan Sewandono, over moderne Indonesische schilders in Nederlands-Indië vanaf de jaren '30.

Lezing: Remco Raben - The modern art & literature of the Indies/Indonesia

In zijn lezing gaat Remco Raben in op de culturele discoursen in Indonesië in de jaren '40 en '50.

Lezingenreeks: De invloed van kolonialisme op kunstuitingen in voormalige Nederlandse koloniën

De leerstoel Nederlands-Caraïbische Letteren van de Universiteit van Amsterdam en Framer Framed organiseren een reeks open lezingen in maart en april 2017.

Magazine

Verslag: Exploring oral history as autobiography in the Curaçaoan context

Verslag: Lezing Gábor Pusztai - Het werk van László Székely

Verslag: What is modern Indonesian art?