The vanishing art in the Northern district of Amsterdam, by Chris Keulemans

For the event, Public Art Amsterdam, writer and founder of the Tolhuistuin Chris Keulemans created a podcast about a city district close to his heart. In two special live sessions on 25 July and 11 September 2018, he takes us along the IJ bank in Amsterdam Noord – a part of the city that has changed dramatically over the past decade to talk about its vanished art.

Ten years ago, it was quiet on the ferry from Central to North. People silently smoked a cigarette and stared into the distance. Hardly anyone had a smartphone yet. Hipster bikes did not exist. The hipster itself had not yet been invented. The Canta car was there, of course. Across the street was exactly one café: Café de Pont. A good place for beer, an uitsmijter and hamburgers.

To the left of the ferry were the fences of the Shell oil company, behind it only water. The cycle path, the terrace of the Tolhuistuin, the bridge and even the Eye, the film museum; all that was still water. It was only in the spring of 2008, when Shell started to withdraw, that land was raised. From then on, art also popped up along the bank. Funny, stark, reflective or activist sculptures. Often made for temporality, sometimes with the hope of longer. Now they are all gone. There is no longer a trace of the effect they intended, and sometimes actually had.

In the garden of the former porter’s house, just behind Café de Pont, for six weeks a little grey structure that looked not much friendlier than an East German border post appeared. It was Hotel Experimenta by designer Jan Konings. It fitted exactly a double bed, nothing more. The idea was: the whole neighbourhood is the hotel. Looking for breakfast, bathroom, laundry or hairdresser? Walk out the door and you’re going to find them.

Hotel Experimenta was part of Urban Play, one of 13 interventions, tools and play elements set up by Droog Design along the banks of the IJ. ‘Through the creative interventions and the input of the urbanite,’ Droog wrote, ‘this experiment in urban design raises political and social questions in the city itself. How tolerant are we of residents’ interaction with the physical city? What does this say about the freedom of city dwellers to be creative in their own city? And who has the final say in this?’

Jan Konings, Hotel Experimenta (Amsterdam, 2008)

The Eye film museum did not ask political and social questions in that summer of 2008. The fact they moved from Vondelpark to Noord, as the first cultural institution of its size, was a statement in itself. The iconic building was still on the drawing board. But to greet their new neighbours, they already put up a big screen on the white sand and screened James Bond’s Casino Royale in the open air.

A little later, the residents’ association Amsterdam Noord Groene Stad aan het Water (ANGSAW) turned that same beach into a sculpture garden. Sculptures of wood, bronze, zinc and stone were scattered over the shore like chess pieces after a losing game. Under the October clouds, a defiant beauty emanated from them, as if those sculptures defied the future to set foot here.

However, the future was irrevocably on its way. In the second half of 2009, Shell’s abandoned canteen, now the restaurant THT, became the playground for the nightmares and wishful thinking of artists, designers and architects. The sprawling space with its grey, rutted carpets, the alcoves and corners of the beehive-like building, with the windows on all sides, made for a moody but seductive exhibition space in that brief period between Shell and the Purmerend-on-legs that stands there now.

The first exhibition was Weak Signals, Wild Cards (2009) by young, international curators of de Appel. They had bivouacked in Noord for six months and saw through the eyes of property developers how residential towers, fancy catering and flats were to rise here on the waterfront. They marvelled at the policymakers and their blind faith in the Creative City, which would be inhabited entirely by, as it was called, “independent, resourceful individuals who are constantly improving themselves. In the vernacular: hipsters. Could things be different, the curators wondered, when the financial crisis brought the development of the Northern IJ bank to a halt. They asked: ‘What other forms of community are possible apart from what the developers envision? And what kind of public art could you make for these alternative communities?’

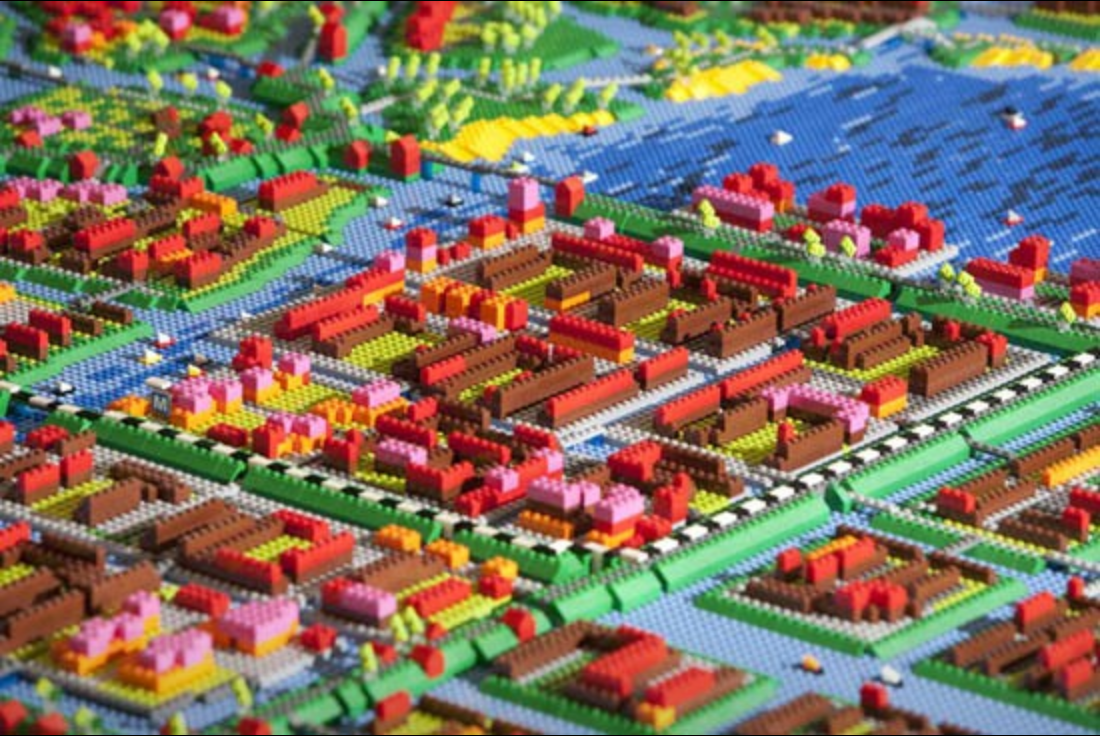

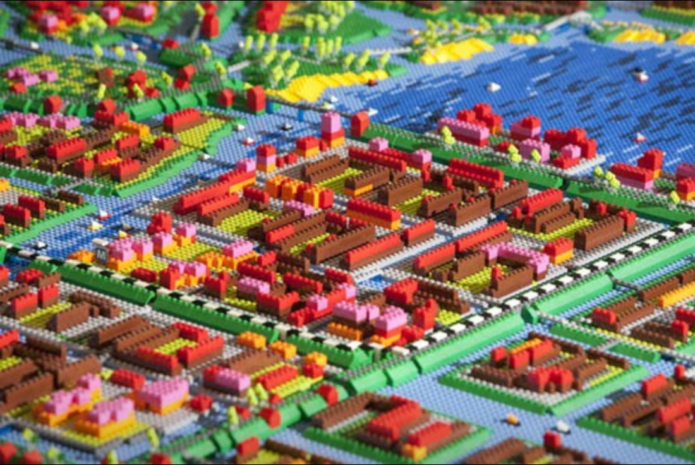

The exhibition Amsterdam Vrijstaat, part of the International Architecture Biennale, also saw that the crisis offered space. Zef Hemel, now Professor of Urban Issues, invited nine urban planning firms to make a large scale model for the future metropolis. Hemel did not want feasible plans, nor utopias. What he did want were answers in the making to the questions that seemed crucial to him for the city of the future. Can chance, inspiration and spontaneity have a place in the planning process? How much room is there for experimentation? Is planning conceivable that is layered, incomplete, full of contradiction, in some ways chaotic, open?’ One of the models was by bureau Urhahn. They imagined a free state in Noord: 100 plots of the Vliegenbos issued to residents with good initiatives. A Ferris wheel, a permanent car boot market, vegetable gardens and small festivals. It did not have to be implemented and it was not implemented. Because professionals only talk about chaotic, open planning as long as there is no money to actually make plans come true.

HOSPER landschapsarchitectuur en stedebouw, ‘Watervrijstaat Gaasperdam’ (2009)

Next to the empty canteen was a pontoon with a round glass roof, also lying empty. Infocentre Overhoeks was superfluous, now that construction had been halted and thus no more houses needed to be sold. From the Tolhuistuin, we organised the three-day Nobody’s Land: visions for the wasteland there. It was October 2011. We looked out over the 51 hectares of land Shell had left behind. All the laboratories, offices and sheds had been demolished. The toxic land lay there like a moonscape. Architect Ekim Tan presented Play North! in that same pontoon. Citizens, administrators, civil servants, artists and developers stood together around a large table with the map of the area. In teams, they were allowed to place coloured cubes – rental houses, houses for sale, amenities etcetera – where they thought it best. After a long weekend, there was a collective maquette that differed in every way from what we find on Overhoeks today.

Two kilometres away, on the other side of the wasteland, a half-demolished little building looked on with a broad smile. An unknown artist had painted two eyes on it, a yellow nose and red lipstick around the estimable hollow in the wall. It stood there smiling for a long time before it too had to be razed to the ground.

In all those plans, there was no space for wandering: the directionless reverie, familiar to every city dweller, and especially those not born here. The bobbing along the street, observing all that movement around you, as if everyone else is sure of where they came from and where they are heading. In an area where everything revolves around real estate and square-metre prices, there is no room for such musings – but they are in place. Sarah Payton, artist and Northerner of Amsterdam (from American descent), understood this. On the bank next to the ferry in July 2012, she placed binoculars made of rusting steel on a concrete base. If you looked through it, you would not see the other side but her meandering film images of the city, with music by Machine Factory under her directionless musing voice-over.

Sarah Payton, What is seems to be / Wat het lijkt te zijn (2013), video installatie

In the two years before construction resumed, a few artists paused. They asked what will be left of the planet if we continue to produce so mercilessly. Peter Smith, who creates huge works of art from carelessly abandoned materials, placed a five-metre-diameter globe in the IJ in 2012, made entirely from plastic bottles. Smith is an artist with a mission. ‘This is the most unnecessary environmental problem we have,’ he said. ‘If all Dutch people cleaned up a piece of litter once a week, there would be nothing left.’ The globe is now in the Iguana reptile zoo in Vlissingen.

Foto: Peter Smit

It was then moved to the foot of the vacant Shell Tower. On its ground floor, the Tijdelijk Museum (the Temporary Museum), an initiative by Nathalie Faber and Claartje Kortbeek, was open all summer. Across Amsterdam at the time, 1.3 million square metres of office space stood empty for more than a year. Faber and Kortbeek invited artists to temporarily re-energise such spaces – with work that dealt with sustainability. A wind-powered knitting machine, Dutch still-lifes made of recycled plastic and Arne Hendriks’ research into the shrinking of the human species, which would help us solve the energy and food problem.

A year later, to get us used to what it is like to be small, Hendriks devised a giant kitchen table and two kitchen chairs. On 4 and 5 May 2013, they stood on Dam Square. The Telegraph wrote: “The table, as big as a small house, was designed and built by Stichting Stadshout, a collective of furniture makers, woodworkers, designers, and an arborist. Founder and furniture maker Crisow von Schulz says: “We collect and process trees from our own city. For this table, logs were processed from all parts of Amsterdam. The chairs are almost completely made from a poplar tree from Prinses Irenestraat, the table includes an elm from Vliegenbos and lime trees from Orteliusstraat.” The table and chairs were impressive, Amsterdam-style, durable and fun. From Dam Square, they moved to the bank next to the ferry. They were climbed and thanked day and night. But the IJ promenade was finished in the meantime. The Eye was open, so too was the Tolhuistuin a little later, and the A’DAM Tower followed in 2016. On Overhoeks, flat blocks were springing up again after a long construction halt. And that kitchen table was no longer fun but a management hazard.

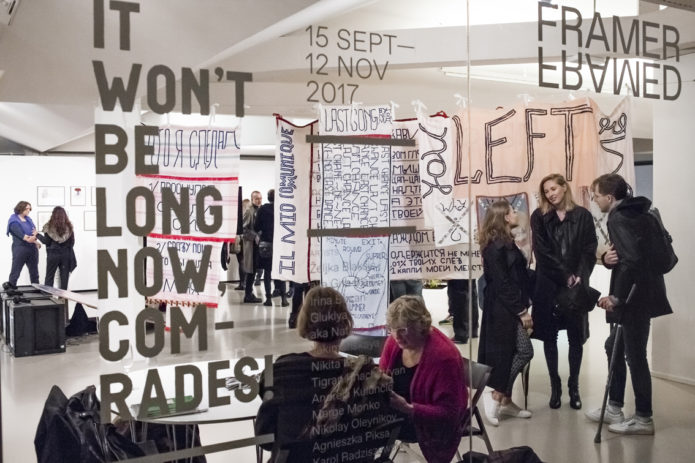

Hotel Experimenta, the sculpture garden, the exhibitions in the empty canteen, the smiling little building, Payton’s viewer, Smith’s globe, Hendriks’ kitchen table and the Temporary Museum; they are all gone. So are the political questions they posed, the alternative communities, the spontaneity in the planning process, the collective maquettes, the musings on identities, the critique of merciless reproduction. There is still plenty of art, critical too, but for that you now have to go inside, at Framer Framed, the Eye or the Amsterdam School of the Arts (Hogeschool voor de Kunsten).

Noel Ed De Leon, Performance at the Northern IJ-river bank (2018). Photo: Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed

I am reminded of the only work of art that the Overhoeks development consortium itself commissioned. It was also the only abstract one. Sometime in 2007, a small pyramid of plastic suddenly appeared in the water, near the future Eye. I have not been able to trace the name and maker of the work. At night, it was supposed to be illuminated. But mostly it remained dark. The power supply proved difficult to maintain. One day it was gone. Ten years later, I think: the masters of temporality are not the artists themselves. They choose temporariness only when they have to and when they are allowed to. They have not managed to make themselves indispensable. The true masters are the administrators and developers. They are the ones who create the space for all those funny, stark, reflective or activist images. They make it possible and sometimes they even help pay for it. Until it is time to finish the work. Then it’s out with the art.

I stand on Eye’s terrace and look around me. I am reminded of the questions Droog Design posed in 2008: ‘Through creative interventions and input from the urbanite, this experiment in urban design raises political and social questions in the city itself. How tolerant are we of residents’ interaction with the physical city? What does this say about the freedom of city dwellers to be creative in their own city? And who has the final say in this?’

By Chris Keulemans

The Dutch version of this text can be listened to as a podcast here.

‘Monuments to the Unsung’ on the Northern IJ bank

From 22 June – 30 September 2018, Framer Framed presented the exhibition Monuments to the Unsung (2018) on the North Bank of the IJ, taking as its starting point the increasing gentrification and rapid changes of the city, specifically that of its ‘own’ district of Amsterdam-Noord, and asks the question: who does the city actually belong to, and who decides what happens to it?

The exhibition is part of the event Public Art Amsterdam – Pay Attention Please! Eleven leading Amsterdam art institutions, including Framer Framed, are joining forces to show the richness of public space in Amsterdam in summer 2018.

Suat Ögüt, The First Turk Immigrant or the Nameless Heroes of the Revolution (2012-2018). Photo: Framer Framed / Eva Broekema

The exhibition is an ode to vanished, oppressed and marginalised voices and stories. How telling that on 8 August, Framer Framed received a letter from a lawyer of our neighbours, the Sir Adam Hotel, objecting to the display of Suat Ogut‘s work The First Turk Immigrant or the Nameless Heroes of the Revolution (2012-2018), which Framer Framed placed in public space as part of Public Art Amsterdam. It illustrates the tense relationship between commercial interests and cultural activities on the northern IJ bank.

Xenson Znja, Performance at the Northern IJ-river bank (1 september 2015). Photo: Framer Framed / Laura E. Tompa

- Het Parool - Kunstplatform Framer Framed verhuist naar Oost

- Trouw - De Nederlandse buitenkunst is nogal braaf, maar is dat erg?

- Groene Amsterdammer - Framer Framed, De Appel en de stad

- Metropolis M - Amsterdam ontdekt zijn kunst en publieke ruimte

- Public Art Amsterdam

Links

Amsterdam Noord / Gentrification / Art in Public Space /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Monuments to the Unsung - Public Art Amsterdam

Part of the collaborative art manifestation Pay Attention Please! in the public space of Amsterdam

Agenda

Guided Tour: Art on the Northern IJ-river bank in Amsterdam

In the context of Public Art Amsterdam and Framer Framed's outdoor exhibition 'Monuments to the Unsung'.

Guided Tour: The disappearing of art in Amsterdam-Noord, by Chris Keulemans and Massih Hutak

Part of Public Art Amsterdam and Framer Framed's outdoor exhibition 'Monuments to the Unsung'.

Network

Chris Keulemans

Author

Magazine

Framer Framed, De Appel en de stad - door Joke de Wolf

Letter: Platform BK - A letter about real estate and the art climate in Amsterdam

Unsolicited Advice: from the Amsterdam Art Council to the Councilor