Romuald Hazoume's “Ear Splitting,” made of brush, speakers and plastic can (left). A portrait mask from Ivory Coast at the Metropolitan Museum (right). Left, CAAC/Pigozzi Collection, Geneva; Right, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Romuald Hazoume's “Ear Splitting,” made of brush, speakers and plastic can (left). A portrait mask from Ivory Coast at the Metropolitan Museum (right). Left, CAAC/Pigozzi Collection, Geneva; Right, Metropolitan Museum of Art The distinction between western and non-western art is outdated

Dutch museums should be freed from the shackles of colonial relations. This will enable them to look beyond the limits of their traditional area’s of interest.

Historic colonial boundaries still divide the world into the West and the non-West. Dutch museums reflect these old colonial visions and relationships: our art museums focus mainly on the Western European and North American modern and contemporary art, while the ethnological museums deal with ‘non-western art. The question is whether or not its time to change these historic divisions.

Three reasons can be identified for the continuing existence of this division. First, many Dutch art and ethnographic museums were born out of the nineteenth century, making colonialism an essential part of their history. Second, in their more than 150-years of coexistence, art and ethnographic museums rarely worked together; sharing knowledge, experience and expertise is not a common practice. Thirdly, international post-colonial critique has been of limited influence on

Dutch art-historical discourse. Dutch universities focus their education and research on the canon of Western art, thus training future generations of art historians an ethnocentric worldview. Chapters in art history textbooks dealing with Chinese and Islamic art are systematically neglected.

The distinction between Western and non-Western artists is problematic. Today’s modern contemporary art is largely transnational. It relates itself to ever changing forms of local, national and international contexts. We find in today’s cosmopolitan world artists from all over the world staged amongst a wide variety of settings. The traditional dividing line between Western art and non-Western art is overtaken by another reality, where the central position of the Western art world has been replaced by a postmodern mosaic of local art centers with international claims.

For example, in Asia a strong art environment developed since decolonization, which has long been ignored by Dutch art museums. Outside the Netherlands there is a stronger degree of integration of new artists generations in the establishment of traditional museums. The Singapore Art Museum, Kiasma in Helsinki and the Sao Paulo Museum of Art, for example, have been integrating art from all over the world for years.

How do ethnographic and art historical museums in the Netherlands want to deal with contemporary art, more specifically, global art, on global level? Since the 1980‘s, there has been an ongoing debate within ethnographic museums about the position of international contemporary art in relation to their traditional roles and anthropological focus. During a discussion in 1985 at the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam wether or not to collect non-Western contemporary art the participating museums of art concluded that they should leave this task to the ethnographic museums.

Last year the staff of the Tropenmuseum together with guest curator Wouter Welling’ restated the exhibition and purchasing policy. The museum will focus on artists who do not feel the need to set themselves off from their own background or feel as if it is something they need to desperately hold onto, but instead investigate the (international) context in which they live and work. Cultural identity and multiculturalism go hand in hand. The museum sees the works of these glocal artists as an opportunity to reflect on the multi-ethnic reality of today’s world. For many art museums, such an approach is considered to be overly politically correct. At the same time it seems that these museums themselves are unable to cross the boundaries of their traditional area’s of interest.

An ongoing discussion is needed between ethnographic and art museums on ways to collect and display works of modern contemporary art, in order to achieve an exchange of knowledge, experience and expertise. When it comes to comprehend the role and position of artists from all continents in the transcontinental global art canon, art museums and ethnographic museums seem to possess extraordinarily complementary knowledge and experience. The time is right to transform the tension that has long existed into a new creative energy.

In the 19th century the museum served as a perfect community to exhibit distant worlds. Major processes of globalization and global diaspora now necessitate a more cosmopolitan approach to contemporary art and culture. It would be nice if the Dutch audience could reflect on these recent cultural developments in museums. The Dutch museum sector stand to gain from freeing itself from the shackles of historical, colonial relations.

By Lejo Schenk and Meta Knol

Background

This article was published on the occasion of the symposium The Colonial Gaze which Framer Framed organized on December 13, 2009 at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht in the context of the exhibition Beyond the Dutch. Indonesia, the Netherlands and the visual arts since 1900, curated by Enin Supryanto and Meta Knol, board member of Framer Framed.

Lejo Schenk is director of the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam.

Meta Knol is director of Museum the Lakenhal in Leiden and curator of the exhibition Beyond the Dutch. Indonesia, the Netherlands and the visual arts since 1900 at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht.

For more on the subject download the publication Decolonising Museums below:

- Publication: Decolonising Museums

Attachments

Museology / Global Art History /

Agenda

The Colonial Gaze

On the historical preconceptions that determine our view of art.

Network

Meta Knol

Art historian

Magazine

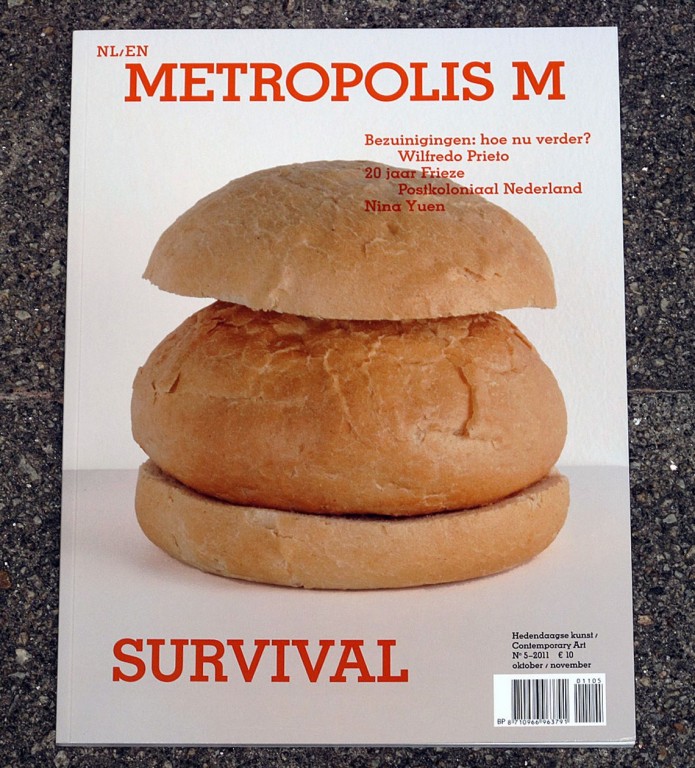

The Netherlands in Post-Colonial Perspective

Het museum als instituut staat ter discussie (Dutch)

Article: Art Around the Globe