Sara Blokland, Reproduction of Family, part 2 (2008) Collectie Nederlands Foto Museum.

Sara Blokland, Reproduction of Family, part 2 (2008) Collectie Nederlands Foto Museum. Verslag: Sara Blokland on Srefidensi and Reproduction of Family

During March and April 2017, Framer Framed organised, together with the chair of Dutch-Caribbean Literature at the University of Amsterdam – Prof. Dr. Michiel van Kempen –, a series of open lectures on the connection and influence of colonialism and Dutch imperialism on different forms of artistic expression in the former Dutch colonies (including visual art, literature, photography, and others).

It was within this context that on the 11th of April 2017, Sara Blokland, a visual artist, independent researcher, and photography curator, gave a lecture entitled Srefidensi and the reproduction of a family history. Her presentation was grounded in her work over the past 10 years; including the series Reproduction of Family, from part 1 (2006) to part 5 (coming in 2017), and her research and curatorial work SrefidensiFoto. As is usual in these open lectures, Dr. Michiel van Kempen introduced the event, highlighting the different focuses and working concepts of the artist; including the topics of colonial legacy and identity, and how these are reflected and performed through the medium of photography.

Sara Blokland took to the stage after Michiel van Kempen’s short introduction. She divided her presentation in two parts: first she spoke about her independent work, and then she dived into her research and curatorial project Srefidensi. To explain both her artistic and curatorial work, she highlighted the strong connection her practice has with both photography and social history. Although Blokland explained that there are no major differences between her work as an artist and her work as a curator, she did point out that her artistic production often stems from personal stories and then connects to broader themes; whereas these themes are typically the starting point for her research, which later connects to personal histories.

When working with a photograph, Blokland explained that she does not simply see its content, but also the mechanics of creation, reception, and use that surround it. In her own words, she is interested in the “redefinition of the photographic image through location, production, and audience”. In relation to this, Blokland drew upon theorist and writer Kobena Mercer’s words to emphasize the dangers of revisiting historical photographs, and projecting on them only what one wants to see. In the case of images belonging to a colonial past, the artist warned that this might be “oppression and nothing else”. In line with Mercer’s arguments, she called this projection of feelings or expectations “blindness”. By reflecting on this blindness, the artist wants to explore “a new relation towards colonial and postcolonial history” (quoting her lecture).

Having introduced the framework of her practice, the artist then presented several of her thoughts and projects. She started with the emotive story of one small, blurred photograph that shows a black man dressed in a military uniform with a riffle in hand; which she had received together with a letter when she was 18 years old. The photograph and letter were of her brother, who introduced himself to her via post from Surinaam; it was the first – and only – photograph she would receive from him. Here, the description of the image and recollection of how she felt when she received it inevitably link to broader – and yet still very personal – topics. The country of Surinaam (where her father and brother are from) seemed to her far away and exotic, as did the image of a black man – the latter simultaneously familiar and unknown at the same time. As the artist explained, “the picture reminded me of photographs I had already seen before. […] The black man was already constructed for me within a visual culture in which he had no choice but to be the other” – a figure that she could sometimes relate to.

When speaking about what her brother’s picture meant to her, and explaining her thoughts on which picture to send back to him, the artist illustrated how any photograph she could have chosen would have signified much more than a simple picture (an image of her and her father, for instance, would signify family unity when received by her brother). Following these thoughts, the artist initiated her project Reproduction of Family; a series of installations related to her own family history, particularly focusing on migration, colonial history, and identity.

After this, the artist showed the audience three short films titled Roos not made for you Roos, Roos, and Tissue. The first video presented a succession of different portraits of the same child, looking both to the camera and away from it, presumably taken on the same day. These are accompanied by a voice narration illustrating the process of taking the photographs and the thoughts and emotions involved in it, relating the images not only to the personal sphere but also to their meaning in a larger, social context (for instance, by bringing up the issue of privacy in relation to an image of a child). The second video, Roos, showed a picture of the same child that appeared in the first video, taken with a Blackberry phone; and the third video – Tissue – is a picture of the artist herself, taken when she had an allergic reaction.

Sara Blokland further explained that these videos were part of a bigger installation: Reproduction of Family part 3: butterflies don’t exist (2008 – 2012). For this installation, the videos were exhibited together with other personal images that showed continuously on TV monitors; exploring how different stories can stem from pictures of her and her family, and how the body becomes both the subject and object of the display (in the artist’s own words). Interestingly, some videos exhibited in this installation do have more of a video-like quality; whilst others (such as the ones she showed at this lecture) are more like a succession of pictures.

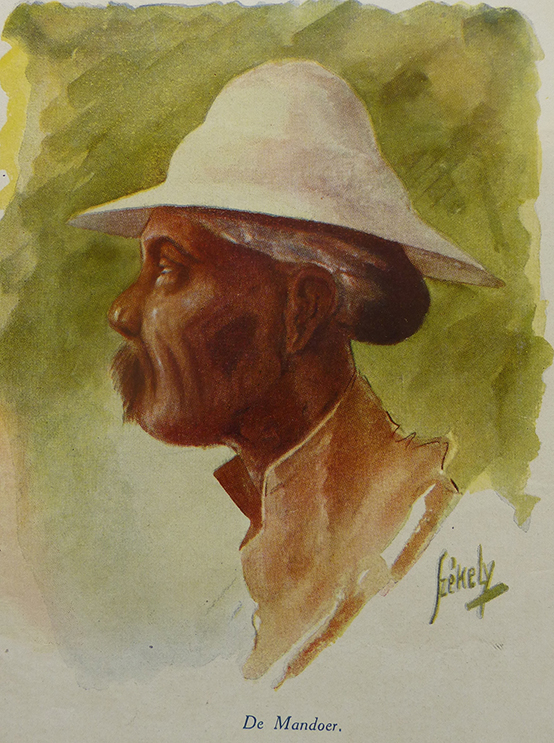

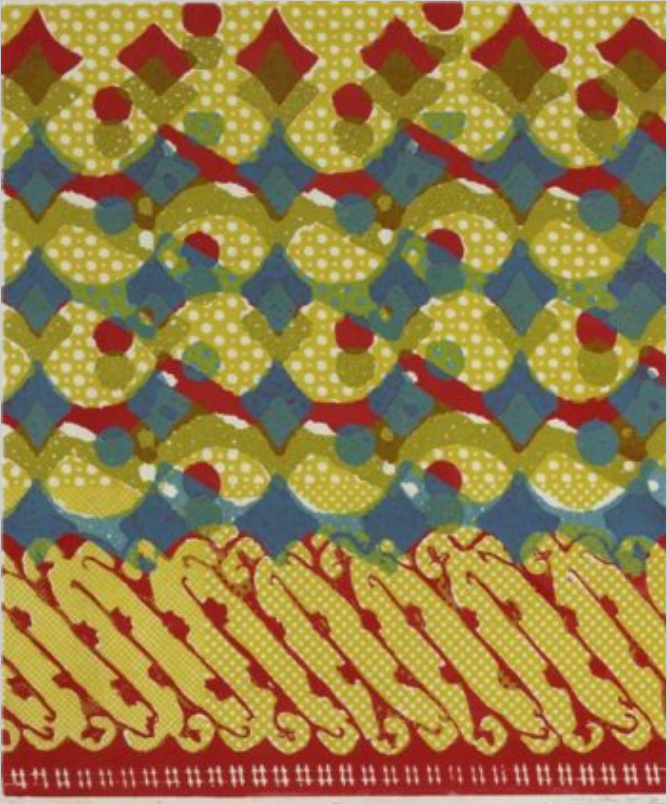

To blend the medium of photography into other disciplines or materials – and therefore to see a photographic image in a different context than the usual (in her own words) – is also something Blokland incorporated into Reproduction of Family part 2 (2007 – 2008). In this installation, she printed some of her family’s photographs on ceramic cups and plates, and placed these on books about different topics, including texts on tropical plants (and how to keep them in a non-tropical environment) and an old Dutch print against mixed marriages. As the artist explained in her presentation, in this artwork the private image is exhibited as a museum object (a mundane one, nonetheless). Displaying these photographs together with the books as part of an installation allows the images to transcend from the private to the public sphere; suggesting the creation of stories and narratives that resonate with many wider themes – such as family heritage, identity, and colonial history. Following the series Reproduction of Family, Blokland introduced another project she took on when she first travelled to Surinaam, together with her Surinamese father, in 2009. Here, she focused (in her own words) on “photography as an experience”; and wrote a diary composed by (partly fictional) text, photographs, and family facts and history.

After briefly delving into this project, the artist changed her focus and continued her lecture by zooming into the history of her mother, who is a Jewish Amsterdammer. To do so, she presented her multimedia installation Reproduction of family part 4: Mother’s history – a library of language (2014 – 2015); which moves away from the history and legacy of colonialism to explore the history of pre- and post-World War II, as well as the relationship between photography and language. The project includes a series of interviews with her mother “about her (Jewish) identity, idealism and memories of her post-war childhood”[1]; connecting these to the philosophy of her mother’s grandfather, Gerrit Mannoury. Mannoury’s work on language generated, in the artist’s own words, “an artistic investigation of (Jewish) identity and (the impossibility of) visualizing trauma”[2]. In her presentation, Sara Blokland showed some of these interviews (made into a video format), and the emotional weight of the work flooded the room. As the artist explained in her presentation, “[this] is a history of shame, exclusion, fear; but also, a history of survival, language, and taboos”.

Steering her lecture towards the last project she would introduce, the artist moved away from her Reproduction of family series to speak about her ongoing Srefidensi project. Srefidensi is a research project initiated by FotoDok and Sara Blokland in 2015; the year that marked the 40th anniversary of Surinam’s independence from Dutch colonial rule. It zooms into the Surinamese context, and explores how photography can capture emancipation and resistance by asking the following question: in what manner does an image (re)present colonial history, even if it does not intend to? To navigate these issues, the artist is focusing on moments of protest and resistance that were captured on camera, prior to – and up until – the independence of the country in 1975.

Srefidensi consists of a website (http://srefidensifoto.org/), six visual papers that the artist is creating together with graphic designer Yvonne van Versendaal, and a series of events that are organized throughout June 2017. To delve into the work, Blokland presented three sequences of pictures – archives, or case-studies – that are part of the Srefidensi research project. The first case-study was a series of photographs of a big stone sculpture of Princess Wilhelmina that was placed in Paramaribo, Surinam. The power position that the statue commanded in relation to its surroundings was striking (for instance, many of these photographs were taken from a lower angle). Eventually, the sculpture was taken away from Paramaribo in the middle of the night due to the animosity it created.

A second case-study Sara Blokland presented was a series of images of Wim Bos Verschuur; a politician and artist from Surinam who studied in the Netherlands in the 1930s, and was active in protesting against the governor of Surinam in the 1950s. The photographs display him holding both a knife and a flower, an arrangement that corresponds with his slogan “a knife for a knife, a flower for a flower” – thus markedly illustrating his protest within the photograph itself (quoting the artist’s words). Lastly, towards the end of her lecture Sara Blokland showed her third case-study: a series of photographs of a 3-day protest march organised by indigenous peoples of Surinam in 1976, claiming their rights amidst the recent independence of the country. The images were taken by photographer Cary Markerink, one of the few witnesses of the march; and are notably accurate in capturing the protest – which went, sadly, largely unnoticed. Additionally, the artist is also interviewing people who were involved in or experienced the march; reconstructing and remembering the event together with them.

Sara Blokland closed her presentation by answering questions from the audience. She discussed several issues related to her work – including the concept of exoticism in her brother’s photo, and the feeling of shame her mother speaks about in the Mother’s history – a library of language video. After addressing a last question on her research of the 1976 protest of indigenous Surinamese peoples (and the use she will give to the interviews she made), Prof. Dr. Michiel van Kempen took over and approached a member of the audience who also witnessed the march – he was a doctor, driving with the protestors. The audience member briefly touched upon his experience of the march, and mentioned how challenging the end of the protest became. His words concluded the event; as the importance of photography in not only remembering, but also interpreting and re-evaluating the past became clear.

Report written by Iona Sharp Casas and edited by Hannah Vollam

[1] Quote from Sara Blokland’s website: https://sarablokland.com/mothers-history-a-library-of-language/

[2] Ibid.

- Fotodok - Utrecht

- Srefidensi - Fotografisch perspectief op de Surinaamse geschiedenis

- Persoonlijke website van Sara Blokland

Links

Fotografie / Gedeeld erfgoed / Koloniale geschiedenis / Suriname /

Agenda

Lezing: Sara Blokland - Srefidensi and the reproduction of a family history

Lezing door Sara Blokland, over haar werk en het project SrefidensiFoto, fotoarchieven en de rol van herinnering en identiteit in haar werk.

Lezingenreeks: De invloed van kolonialisme op kunstuitingen in voormalige Nederlandse koloniën

De leerstoel Nederlands-Caraïbische Letteren van de Universiteit van Amsterdam en Framer Framed organiseren een reeks open lezingen in maart en april 2017.

Netwerk

Sara Blokland

Kunstenaar, curator

Magazine

Verslag: Exploring oral history as autobiography in the Curaçaoan context

Verslag: Lezing Gábor Pusztai - Het werk van László Székely

Verslag: What is modern Indonesian art?