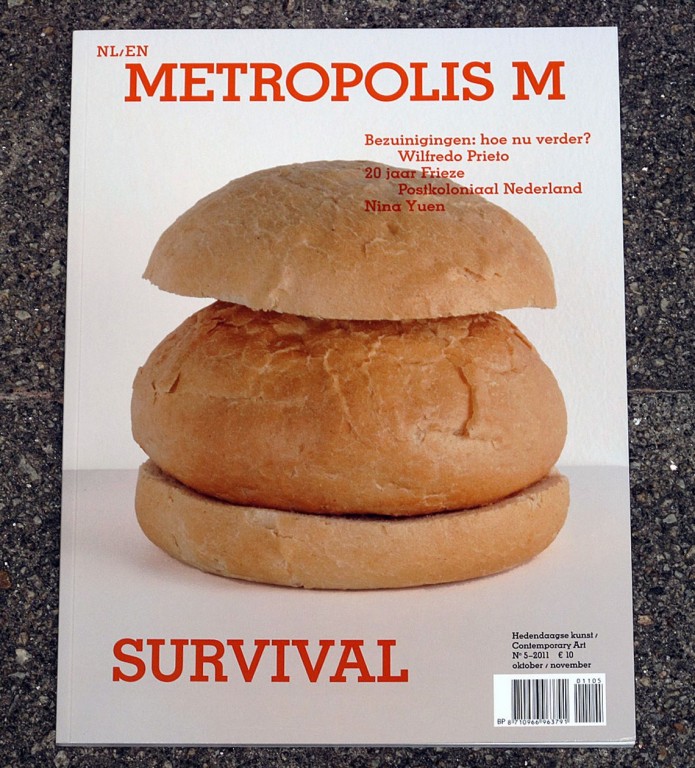

Metropolis M, Regels & Taboes (n. 4, 2014)

Metropolis M, Regels & Taboes (n. 4, 2014) Article: Globalisation in Dutch Art Centres, by Vincent van Velsen

For a long time, Dutch art centres have been criticised for being closed off to developments in art taking place outside of Europe. Now that a new generation of directors and curators is in power, the question arises as to what actions they are initiating to address this problem. Vincent van Velsen spoke with a number of involved parties about their current policy.

In 2006, Meta Knol, Edwin Jacobs and Stijn Huijts wrote their manifesto Naar een mondig museum (Manifesto for an enfranchised museum). The manifesto claimed that the Dutch art world was dominated by the ‘egocentrism and the dominant, western ethnocentrism’. Eight years later, Meta Knol, at that time curator of the Centraal Museum under Sjarel Ex, and now director of the Lakenhal, feels that ‘there is growing realisation that the effects of globalisation in the arts are inescapable. Still, it is undeniable that many Dutch art centres missed the boat and have a lot of catching up to do’.

According to Annie Fletcher, curator of contemporary art at the Van Abbemuseum in the Netherlands, an international collection usually means works from Germany, Belgium, the UK and America. At the same time, programmes are largely defined by the collection and the presentation possibilities in museums. In this sense, L’lnternationale, the exchange programme between various European museums, including the Van Abbemuseum, is a good opportunity to transcend the constraints imposed by a museum’s house collection, knowledge and expertise.

All the representatives of the institutes I interviewed are looking for ways to open their collections to new influences. The space to do this appears to be limited however. Past policy for compiling a collection inevitably defines the possibilities for the near future. Jelle Bouwhuis, curator of the SMBA, admits that the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam hardly owns any non-western art. It is true that works were bought from the Project 1975 (2014), a long-term research project initiated by SMBA to explore art in Africa; but only a few pieces of art were ever purchased, which precludes extensive exhibition.

Stijn Huijts, as director of Het Domein Sittard, contributed to the manifesto Towards an Engaged Museum. In the same period he also initiated a project called Made in Mirrors, which focused on artistic exchanges between smaller cities in The Netherlands, China, Egypt and Brazil. The goal was to draw attention to cultural diversity. This long-term collaboration led to a substantial exchange of knowledge. Having worked at Schunck in Heerlen for a couple of years, Huijts is now the director of the Bonnefantenmuseum. In this museum he put the focus of the Bonnefanten Award for Contemporary Art 2014 on South America. The jury was comprised of South American specialists in order to profit from their expertise and network, and to have them judge the contestants from a deep knowledge of their cultural context. Also in the current series, Beating around the Bush, artists outside of Europe have been involved in exploring the potential of the house collection. But Huijts admits that it is very hard for a large museum to keep up with relevant developments. Museums are by their very nature, slow-operating organisations.

TATE MODEL

Among large museums, the Tate is often held aloft as an example of a museum that has successfully adapted to the changing times. Last March, the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, together with the Tropenmuseum (now part of the Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (National Museum of World Cultures)) organised the symposium Collecting Geographies, with the goal of discussing the role of non-western art in western art museums from different points of view. The question was raised as to whether the Stedelijk, with two blockbuster exhibitions and a permanent collection without a single non-western artist represented, had the right to facilitate such a gathering. This issue was brought up during the closing speeches at the symposium. Margriet Schavemaker defended the Stedelijk with a remark about the lack of a budget such as that enjoyed by Tate Modern, which can finance a separate team and purchasing budget for every continent. But the Tate model was not praised by everyone. Anke Bangma, curator of modern art at the Tropenmuseum pointed out that it is preferable to critically evaluate the house collection as well as using new accents and targeted purchases to enrich the existing collection and, where necessary, to shift the focus.

To Bangma the situation is even more complex because the Tropenmuseum isn’t a white cube and the historical context plays a relatively large role. Whereas art museums only avail themselves of historical art references and contexts, the Tropenmuseum has to give considerable attention to social, political and historical references. Some references cannot be omitted, whereas that is an option for an art museum. Bangma also sees the advantage to this situation. In the Tropenmuseum, the connection to social issues is far more clearly present. Art museums are chiefly concerned with art and far less attentive to the social context of that art, this in spite of the cross-border nature, both of artists and of the inherent knowledge and purpose of art museums.

ART OR CONTEXT

The Tropenmuseum couldn’t be more different in this sense to the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum. In this museum, the art and the artist take centre stage and the context is only mentioned at all if doing so is necessary to explicate the work itself. According to the director Sjarel Ex, the Boijmans programmes from a perspective of ‘curiosity and interest, based on the immanent characteristics of the art work, not from a socially-critical paradigm or any presupposition. We see art itself as the goal, not as a means to ignite debate on social issues.’

What We Have Overlooked (2016), curated by Mirjam Westen for Framer Framed, Amsterdam

Mirjam Westen, curator of contemporary art at the Arnhem Museum, compiles her exhibitions with a consistent focus on what she describes as ’alternatives to the well-trodden paths’. She actively seeks out artists that are not exhibited elsewhere. For her, art can never be separated from the context from which it derives. Besides the immediately visible layer, the broader and deeper meaning of the work is an essential criterion: an art work must say something about us, about society, about the world. In her exhibitions, her preference for critical engagement emerges. Westen often exhibits non-western work because art and politics are still more intricately interwoven ‘there’ than in most Dutch art. Mirjam Westen wants to make the other self-evident, to ensure there will no longer be a sense of ‘the other’.

HOW TO IMPROVE

Increased knowledge and a self-critical attitude seem to be prerequisites to any improvement in the situation. Maria Hlavajova, artistic director of BAK, points out that ‘many art centres work on autopilot, based on outmoded views. They endlessly reproduce and bolster the western canon, which boils down to rearranging the same objects over and over again.’ In the same context, Jelle Bouwhuis states that most institutes and curators suffer from ‘choice-stress’, a lack of insight or common denominators, combined with a plethora of possibilities, causes them to fall back on the safe clichés in western art that they and everyone else already know and understand.

The same principle applies to travelling, scholarships and studio visits. The thought of passing up on a visit to Bazel or New York and instead exploring the art of Dakar or Accra, occurs to hardly anyone, even though New York is just as far away as those two capital cities. Bouwhuis himself had no clue how to proceed with his long-term Africa Project in 2006. That world seemed too vast for him to comprehend. But doing nothing was not an option. This made him decide to simply begin randomly somewhere; with the result that SMBA and he himself now hold a prominent position in the field of the presentation of, the dissemination of knowledge and the discourse on non-western art in the Netherlands.

Annie Fletcher, curator at the Van Abbemuseum, advocates for the decolonisation of the museum by reconsidering the problematic remnants of colonisation, which, in the case of The Netherlands, will be a tall order. Maria Hlavajova also calls for an evaluation of our own western position, instead of re-evaluating the non-western context. This was already the goal of the research project Former West. In Future Vocabularies BAK will continue to develop this theme.

Hlavajova presents the preconditions for a genuine post-colonial approach as follows: ‘This would mean accepting and fully recognising our own responsibility, including all the painful, problematic and hitherto neglected aspects. In addition to this, an honest dialogue and reciprocal exchange on an equal footing with non-western cultures is essential, instead of continuing a one-sided, condescending monologue – the signature of a colonial mentality. We need to see the world as comprising heterogeneous but equal parts, and we need to show modesty and solidarity. Furthermore, we are required to review global history from a post-colonial and post-communist perspective, in order to contribute to a new understanding of the present.’

Meta Knol doesn’t see a role for De Lakenhal in this endeavour, because the museum is dominated by a historical collection. She did, however, set up Framer Framed in 2009 together with Cas Bool, Josien Pieterse, Nancy Jouwe and Kitty Zijlmans, an initiative ‘to promote knowledge and expertise in the field of intercultural processes in contemporary art’. As of May this year, Framer Framed has a permanent residence in the Tolhuistuin, Amsterdam, where exhibitions are held to reflect this position and increase public awareness. She also advocates that ‘all institutions teaching art history in the Netherlands should include World Art (Kitty Zijlmans wrote a book on this subject in 2006) as a regular part of the curriculum’. In this way more knowledge will be gathered about other cultures so that contemporary art can be understood and interpreted from within other cultures. The idea that there are parallel worlds has not been grasped by all art centres, which makes it difficult for them to engage with new forms of Global Art.

Vincent van Velsen studies the history of architecture at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. This article originally appeared in Metropolis M, Nr 4-2014 Regels & Taboes, 30 September 2014

Museology / Global Art History /

Network