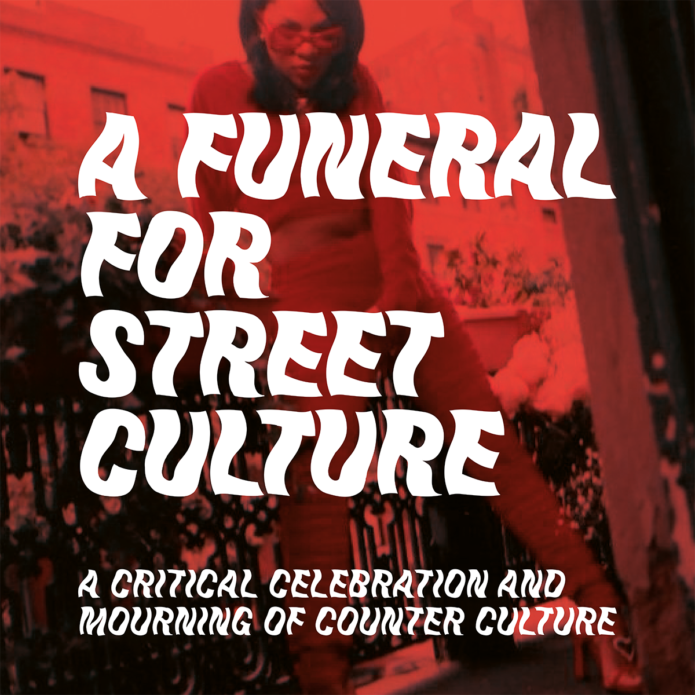

Discomfort as (curatorial) strategy: A Funeral for Street Culture

In this conversation, we talk about the use of discomfort as a curatorial strategy and its necessity for changing the way we experience exhibitions, as well as the institutional and other structures underlying the usual ways of looking and working. In particular, we discuss the ongoing Metro54 project A Funeral for Street Culture, curated by Amal Alhaag and Rita Ouédraogo and hosted by Framer Framed over the summer of 2021.

Irene de Craen,

Editor in Chief of Errant Journal

Installation view of work by Frédérique Albert-Bordenave in A Funeral for Street Culture (2021). Photo by Eva Broekema / Framer Framed

Irene de Craen in conversation with Amal Alhaag and Rita Ouédraogo.

Irene de Craen (IdC): I want to start with your Facebook-post, Amal. You have epic Facebook-posts. It is very nice to follow you there. Sometimes they are a kind of rant, but they are always so sharp. With this one in particular – I was already thinking about doing an issue of Errant Journal on discomfort – I felt you hit on something important. It was in reference to reviews that were written about A Funeral for Street Culture, as well as other exhibitions. Basically your comment is about how reviewers of those projects do not always understand them, because information is not given in the usual ways. You wrote: ‘in times when critique of projects like this in Fort NL takes the shape of “I don’t understand”, which translates to “I am no longer the centre of the world and I don’t know how to hold that space”, something I find personally very interesting, because it is this discomfort which I find truly the most thought-provoking outcome of this edition of Sonsbeek or Metro54’s project at Framer Framed.’ And then you continued: ‘because discomfort as outcome is often not seen as productive intellectual space by white Dutch critics and this process is merely pushed aside or relegated to the illusionary and useless concept of quality. After all, how much longer are we gonna have to engage with this bla bla about the centre of the world, during a time when the so-called proclaimed centre has been slowly dissolving over many, many decades?’

Amal Alhaag (AA): I tend to use them sometimes, the rants, although I call them more notes than rants, as `free thoughts´. But yes, this is something that is often a reality. I am sure Rita has also experienced this with some of her projects, but we also experienced this together during a project we organised at the Research Center for Material Culture (RCMC).

Rita Ouédraogo (RO): Definitely. I think discomfort is always what we are working with. I feel when you are working with institutions and you are trying to do things differently, it creates a lot of discomfort for people. So I think there is actually nothing that we have ever done that was not very uncomfortable for many people. And at the same time, very comfortable for others who were usually overseen. When we are talking about losing certain things for certain people, we are also talking about on whom it is actually lost. That is also what A Funeral for Street Culture is trying to touch upon: what is street culture when it is not ours anymore? What does it do when other people ‘take’ it?

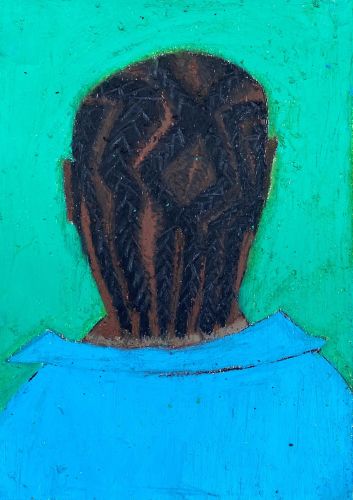

Installation view of work by Oko Ebombo in A Funeral for Street Culture (2021). Photo by Eva Broekema / Framer Framed

IdC: Can you give a bit of a general description of A Funeral for Street Culture?

RO: I think it started out when we were just discussing several things we were seeing in the world. I think we were both seeing that there are so many people of colour and Black people, who were all of a sudden… well, certain Black people, certain people of colour, who were all of a sudden picked up and being super hyped. So we asked ourselves: what does this do? What does it do when you have these Black and brown people or people of colour in certain positions, where it seems as if they are able to really do something? I am talking about Edward Kobina Enninful at Vogue for example, or Virgil Abloh, who recently died, but had a big position at Louis Vuitton, and other Black people occupying important places now. But what does it actually do when the street culture that they are promoting and showing is in a way institutionalised? What does street culture then still do? And what does it do for Black people and people of colour? And do we actually benefit from it or does it only create more inequality? At the same time, what does it mean when all these kinds of street culture elements are all of a sudden taken by or occupied by people who were never part of that culture? Can it still be powerful? Perhaps it can be, it was not to say it is all shit or something, but more like: let’s think about what is happening. I think that is a very big question. So then it also is about holding space and who is holding space. Who do you see in certain positions and what are they actually able to do? How do we celebrate at the same time as being critical of what is happening? This is why we call it a critical celebration, as well as a funeral. Because a funeral is sad but can also be a celebration of life. It can be so many different things in different cultures, and yes, also just a space to be, to mourn at the same time while celebrating.

IdC: I have read a few critical reviews, and some were also very positive of course, but others had problems engaging with the works because of your curatorial strategy. What can you say about that? What was your curatorial strategy and why do you think it gets that response?

AA: It is the thing that I wrote about. Often when one chooses an opaque strategy, people still want to be guided by a curatorial text, by statements and wall texts that fit within the way the white art canon works. There are guidelines that people know they need to reach out to. If you observe the way that people sometimes move in museums, the way that museums often are organised or organise the way people walk, the whole psychological element of experiencing an exhibition is very much based on a Eurocentric notion of being in the world. You walk in these routes in a very linear way, and you have to read the texts, but it is often one way to view the works and when you do not centralise the things people understand as the way they are taught, it creates a discomfort. But instead of engaging in conversation, it becomes a reason to say ‘because I don’t understand, this is not of value.’ While there is a whole other group of people that just walk in the space and read it and go like ‘oh, there are no longer the conditions set that often estrange me.’ Because I have been in many situations where I was like ‘oh, this is interesting.’ I am looking at this work and I am like ‘ok, I think I read this and this into it,’ and I read the wall text and I realise the curator has a particular idea, a way of thinking of how I have to look at this work of a Black artist or a person of colour, while actually the way I read it… the codes or the things I read into it are completely different. And for me, that small invitation, or perhaps provocation, is also what Rita and I address in the project. It is almost necessary to push for a different audience to be welcomed as well. So it is almost as if you are giving up some of the tools that allow certain people to feel welcome, to allow others to take up more space. And that is the friction that keeps coming up.

Installation view of Pillars of Autumn, The Remote HoneyComb Hideout in A Funeral for Street Culture (2021). Photo by Eva Broekema / Framer Framed

IdC: I find it very interesting what you say, because it is really about what we have learned and the codes that we are used to and how we can unlearn it. And not knowing is actually a very good tool for that. Can we accept not knowing?

AA: Yes. And to me it also says a lot about whiteness, because for me personally… I move through the world where all the time I am not the centre, I am never the centre of the world and there is a lot that I do not know and I am fully aware of that. But I come from a culture where not knowing is ok. It is not that special. But in the Western context, not knowing is seen as a form of weakness – although this is slowly changing. And I think that to not have knowledge can sometimes also be a form of knowledge, because you learn different tools of navigating the world, because you have to calculate this part of you that needs to always engage with the estranged. [Édouard] Glissant writes about that, too. For me personally it is always a very enriching space to not know. I sometimes have to remind people, especially white people, that it is ok that you are uncomfortable for one hour. I have been uncomfortable my whole life. Look, I am still healthy! I am good. You will be fine.

RO: I think one of the things we also try to create in the space, and of course it was COVID, so the whole situation was a bit more difficult, but the whole idea was that it is a space where people could just be. So I think in that sense the discomfort and the comfort were really close together. People who might feel uncomfortable could also imagine or experience eventually feeling comfortable with the discomfort.

AA: Rita, I think what you are mentioning is very true. The pandemic influenced this project on many, many levels. And I have to say, it is just so complicated to do these large projects that are people-centric, when people are not allowed to be together. And I think for us it was one of the difficult things, because indeed it was supposed to be a living space, a space that breathes and allows people to do take-overs. It is always wonderful if your audience becomes your co-creator, and I think this project had that potential. What actually happened was that some of the artists became co-curators and became very involved, which was always the intention. There are so many people who are super active; I really want to acknowledge that.

And then in the last event what I appreciated was that it was the intellectual side of the street and the street-street side and the activist side, they all came together and it created this very fiery conversation, which was about: how do we actually speak together, when we sometimes do not completely understand each other? In a sense it was about the vocabulary, the language and the accessibility and the shared agenda of housing rights and issues that connect Amsterdam-Noord with Rotterdam-West and different parts of the country. So I felt that was what we were aiming for, but we only managed to do it because we could collectively cultivate that space when more things were allowed to happen according to the COVID regulations.

Installation view of Stephen Tayo and JeanPaul Paula, An Ode to Christian in A Funeral for Street Culture (2021). Photo by Eva Broekema / Framer Framed

IdC: I’d like to return to discomfort as a strategy, which maybe you have not used intentionally to make people feel uncomfortable, quite the contrary actually. Still the reason why we chose this topic of discomfort for Errant is because it is a productive intellectual space, as you said in your comment. For me, there is also this link to Robin DiAngelo’s essay ‘White Fragility’. There is a quote from her essay that says ‘the continual retreat from discomfort results in a perpetual cycle that works to hold racism in place.’1 The question is: how do you deal with that? Because I am sure that both of you, also in your separate work, can expect a constant pushback in these matters.

AA: Yes. I mean, for me personally it is intentional. It has been intentional for a very long time, that in order to create, to welcome – I would rather speak of welcoming or inviting certain (uninvited) people in – it has to be very uncomfortable for others. Also, my whole presence is uncomfortable for people, as much as there is this weird hype, or you are more recognised now. I think I have not done one project that has been smooth sailing, and the older I have become, the more comfortable I have become in the discomfort. Because as a Black woman, you come into a space and as much as people are so-called aware now, the amount of bullshit and nonsense you are dealing with on a daily basis, even in the friendliest institutions, is truly, truly a waste of time and energy.

And then you always have to check yourself. I use anger as a strategy. Sometimes I am not really angry, but I know shit gets done if I show Black woman anger. Or I know people get super annoyed if I push things through, really. I know they do not expect it or they find it annoying that it takes me three months to work through the contracts and get something signed because I am like ‘I don’t agree with this, and this, and this…’, and I have spoken a lot about this. There was awhile when institutions wanted to work with you, and then you can see in people’s faces that they think, ‘I thought that this was going to be easier.’ Because the more privileged your position becomes, the more – I personally believe – you have to work towards keeping that discomfort alive.

And also I am involved in literally every part. I usually know the cleaners, literally all. I get to move in different departments, because, you know, it is not only curatorial work. If it were merely curatorial work, it would have been easy. And also, if you do not show up as the curator or the artistic leader people let their guards down. Sometimes they can become even more disrespectful because you are not performing hierarchy. And when you refuse to perform, it means sometimes that you have to shake things up a bit, let people know that you are willing to use the hierarchy, if necessary. Sometimes if you are not pushing things through, it means you have to educate people. You have to negotiate; it is a lot of negotiation. The discomfort as curatorial strategy also means that you are always underpaid, because it costs you way more hours and you have to enjoy the process of feeling frustrated or annoyed.

Listen the full conversation here.

KIOSK Rotterdam in A Funeral for Street Culture (2021). Photo: © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

This conversation is a transcription of an episode of Errant Podcast, part of Errant Journal. Which has launched its 3rd issue on DISCOMFORT. This excerpt is re-published with permission of Errant Journal.

Errant Journal is an international publication for cultural theory and practice aimed at bringing together diverse local perspectives on a global scale. By embracing the limits of our situated knowledge and the meaninglessness of a singular vantage point, Errant questions the politics of knowledge and representation through language, art and other disciplines. With its decolonial and pluriversal approach to themed issues related to (a.o.) geo/body-politics, museology, ecocide, and activism, it aims to connect theory with practice in an expansive field of knowledge.

Errant Journal is a concept by Irene de Craen.

Framed Framed is co-publisher and founding partner.

Order your copy of Errant Journal directly online via our webshop.

Gedeeld erfgoed / Curatorial Text / Gentrificatie /

Exposities

Project: A Funeral for Street Culture

Een groepsproject van Metro54 en Rita Ouédraogo gehost door Framer Framed

Agenda

Lancering: Errant Journal #3, DISCOMFORT

Errant Journal is een concept van Irene de Craen, gerealiseerd in samenwerking met Framer Framed

Netwerk

Rita Ouédraogo

Curator, onderzoeker, antropoloog en programmamaker

Irene de Craen

Schrijver, onderzoeker en curator