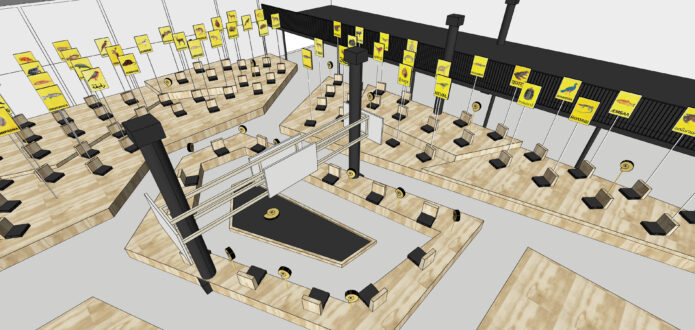

[:nl]Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021), Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: © Ruben Hamelink[:en]Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021). Photo: Ruben Hamelink. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam[:]

[:nl]Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021), Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: © Ruben Hamelink[:en]Radha D'Souza and Jonas Staal, Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021). Photo: Ruben Hamelink. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam[:] From the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes: The Lives and Deaths of Oil

Kunstlicht Magazine is out with a new issue, titled The Worldliness of Oil: Recognition and Relations and is guest edited by Anne Szefer Karlsen and Helga Nyman. Ashley Maum, part of Framer Framed’s research and production team, wrote an article focusing the presence of oil in the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes installation, which can be read below.

by Ashley Maum

October 2021

Within the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)’s Red List of Threatened Species, notes on the conservation of species already extinct often read something like this:

It is not recommended that any further survey work be undertaken for this species.

This species has been extinct for nearly two hundred years and conservation measures are no longer possible.

This species is extinct and does not require protection or management, monitoring, or research action.[1]

These statements have been written with a very scientific, naturalist conception of what it means to conserve in mind. Still, they are nonetheless indicative of a Western mentality toward species extinction, which now occurs en masse as a consequence of the climate and ecological crises and the activities which induce them, including agricultural and urban development, as well as biological resource extraction. It is sadly unsurprising to read statements like those above that brush off the value, meaning, and duty of action which species extinction should arouse in its observers. The broader associations we can conjure for conservation include actions such as care, preservation, keeping back. The Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC), on which this article focuses, proposes such a broadening, specifically of how we might reconfigure interspecies relations in a manner cognizant of our ecological interdependence. This restructuring is offered through the critical activation of the state of extinction encompassed by the CICC’s proposition of intergenerational climate justice.

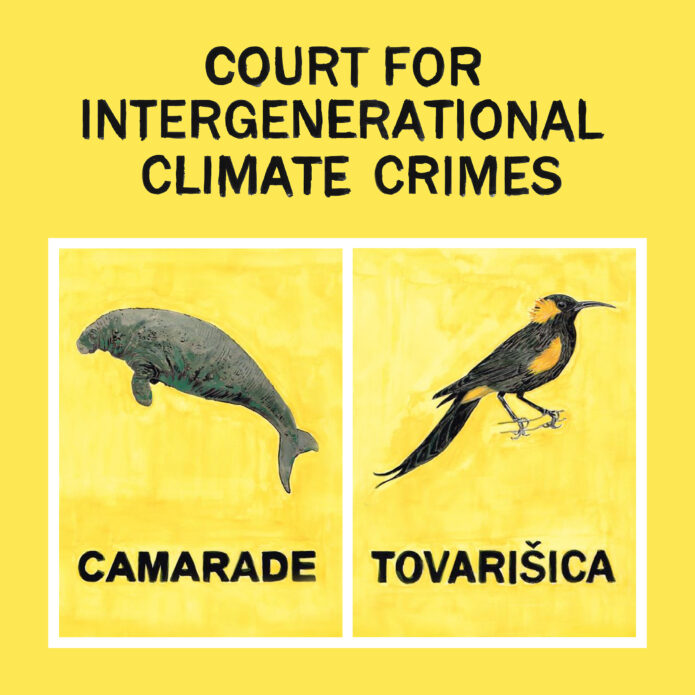

The CICC is a project and performative exhibition initiated by academic, writer, and activist lawyer Radha D’Souza and visual artist Jonas Staal. The project forms a more-than-human tribunal for the prosecution of climate crimes committed by corporations in concert with the state. Opening in September 2021 at Framer Framed, Amsterdam, the court features a large-scale tribunal infrastructure, which, in October, will host four evidentiary hearings against multinational corporations and the Dutch state. D’Souza and Staal identify the relationship between corporations and states as key in the perpetration of intergenerational climate crimes; they thus initiate hearings against corporations registered in the Netherlands: Unilever, ING, Airbus, and other corporations linked to the Netherlands through international investment treaties. The legal framework practiced within the CICC is based on D’Souza’s book What’s Wrong With Rights (2018)—a critique of neoliberal ideation and systems, which underwrite our linear, individualized understanding of law and justice, and play a foundational role in the historical and current trajectory toward climate collapse.[2]

fig. 1 Radha D’Souza & Jonas Staal, ‘Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes’, Study, 2021. Image courtesy of Paul Kuipers and Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

The CICC hosts a more-than-human assembly, as an installation filled with the fossilized remains of ammonites and the representational presences of extinct animals and plants (Figure 1). The inclusion of animals and plants is based on a component of the CICC project titled Comrades in Extinction, which maps species that have gone extinct during the climate and ecological crises. From Comrades in Exinction’s over 500 species, 85 will be visually represented in the CICC installation; the animals through paintings and the plants through woven textiles.[3] Their presence, along with that of the ammonites, establishes the interdependence of human and non-human vulnerability to climate violence. Departing from interdependence, the CICC offers a space and experience of collectivity and collective action with the hope of fostering climate justice today and in the future. This expanded sense of comradeship goes hand in hand with the expanded, intergenerational scope of climate injustice posed by D’Souza and Staal. Crimes of corporations and states will be evidenced as they extend into histories of colonialism. At the same time, the CICC prosecutes climate crimes with a mind toward the extent of their impact to be seen in the future, affecting future generations of human and more-than-human life. The hearings will centre on an acknowledgement of harm carried across past and future, as well as the identification of systemically rooted implication.

By tracing a constellation of oil within the installation, this article explores the experiences of more-than-human collectivity and layered temporality inherent to the CICC.[4] What I refer to as an ‘oil constellation’ is a constitution of three parts—different manifestations of oil with distinct time scales. These three parts are the archival presence of the algae vanvoorstia bennettiana, the physical presence of ammonite fossils, and the basin of oil around which the CICC is centred. This article thus focuses on the physical morphology of the court as it shapes and is shaped by the conceptual layers of the court as it has been imagined by D’Souza and Staal.[5]

Comrades in Extinction

Vanvoorstia bennettiana, or Bennett’s Seaweed, is a species of seaweed presumed to be extinct (Figure 2). It was last seen by humans in 1886 when collected for the second time from the waters of Sydney Harbour. Among its causes of extinction is pollution by oil spills resulting from military and commercial activity in the harbour, beginning with the colonization and industrialization of Australia.[6] Vanvoorstia bennettiana, which I have chosen as an example for its direct link to oil, is one part of the damaged ecology on which the CICC is grounded. This ecology takes the shape of an archival network titled Comrades in Extinction, which records the known plant and animal species that have gone extinct as a result of disrupted climate and the activities that bring its effects to bear.[7] The archive of over 500 species draws from the IUCN’s Red List, but, as the IUCN database tracks extinctions regardless of cause, D’Souza and Staal’s Comrades in Extinction intervenes to draw focus to extinction – closer to destruction – resulting from human activity within systems of settler-colonialism, industrialization, and urbanization.

fig.2 William Henry Harvey, ‘Plate LXI, Claudea Bennettiana [Vanvoorstia Bennettiana], –the natural size. 2. A portion of the network, magnified. 3. A small fragment, more highly magnified’, 1855-1859. Source: Harvey, W.H., ‘Phycologia Australica: Or, A History of Australian Seaweeds; Comprising Coloured Figures and Descriptions of the More Characteristic Marine Algae of New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia, and a Synopsis of all Known Australian Algae’, Vol. II. (London: Lovell Reeve, Henrietta Street, Covent Garden, 1859).

fig 3. Radha D’Souza & Jonas Staal, ‘Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes’, Study, 2021. Image courtesy of Paul Kuipers and Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

Ammonites constitute another non-human presence within the CICC’s more-than-human assembly. They are the fossilized remains of a species of shelled cephalopods—the same class as squid and octopi. Ammonites lived from 450 to 66 million years ago, when the 5th mass extinction occurred and during which most of the species died out. The CICC installation hosts around 30 ammonite fossils. As with the representations of species in Comrades in Extinction, the ammonites rise from the back of a seat shared with a human constituent (Figure 3). D’Souza and Staal write on the fossils’ role in a concept note for the project:

As different as our evolutionary process and lived time might be, ammonites witnessed the 5th mass extinction, as we are witnessing the 6th; they are fossils, and we are fossils in the making. In the CICC the ammonite fossils act as evidence of an extinction of the past, while simultaneously acting as witnesses to the extinction of a present. And it is of course the very same disintegrated bodies of the ammonites, that co-constitutes the oil and gas that fuel our current climate collapse.[8]

This passage highlights a violently normalized fact of fossil fuels: that oil, the burning of which drives the possibility of a shared deep future into further precarity, derives from the bodies of once-living species. The devastation of this lies in the sentience of fossils such as ammonites. They evidence scales of time and life far beyond human conceptual capacities—asserting the fact of pluriversal worlds in a universalized present. Simultaneously, ammonites embody the experience of interrupted climate and mass extinction; a knowledge of which the CICC draws on through their presence.[9]

Sitting within the CICC, ammonites and vanvoorstia bennettiana, two species linked through oil, are posed in a unique relation—as comrades. This relation extends to the court’s human actors and points both to an interdependent vulnerability (and thus need for climate justice), and the interdependence of time scales. The CICC activates a layered, intergenerational temporality by collapsing the distance of time between ammonites (extinct before recorded history), species within Comrades in Extinction (extinct in the last 500 years), and the humans present in the now of the tribunal. This intergenerational span institutes climate crimes as activities with long historical roots converging in the present and forms the frame wherein the CICC considers climate justice, as an endeavour posing impact for future planetary life and worlds.

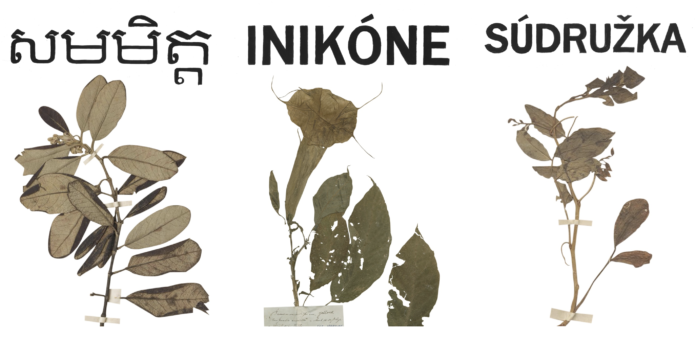

The word ‘Comrade’ in the CICC functions as a system for identification and naming. The term identifies that which it names as co-equal in the struggle toward climate justice, which supersedes any differences of taxonomy. Within Comrades in Extinction, ‘comrade’ is the first identifier of each animal or plant. Together with ammonites, the extinct animals and plants fill the tribunal installation, waiting to be joined by its human actors. Their painted (animals) and woven (plants) depictions are accompanied by the word ‘comrade’ written in different languages (Figures 4-9).[10] The use of ‘comrade’ instead of scientific or common names can be seen as an act of resistance to the process of colonial naming, which goes hand in hand with species extinction.[11] For vanvoorstia bennettiana, discovery and naming occurred coevally with the colonial exploration and settling of its habitat, which led to the industrial- and militarization of Sydney Harbour/ Port Jackson that transformed the site’s conditions into something the seaweed could not withstand.

The connection drawn between ammonites and the seaweed vanvoorstia bennettiana – and other plants and animals present through Comrades in Extinction – delineates the expanse of time touched by climate catastrophe and environmental destruction. For the CICC’s human audience, their presence offers an experience of inter-species collectivity, through a recognition of shared vulnerability and thus stake in climate justice. This encodes non-human lives with a worth removed through the progression of modernity/coloniality and their consequent ‘Othering’.[12]

fig. 4-6 Radha D’Souza & Jonas Staal, ‘Comrades in Extinction’, Studies, 2020- 2021. Images courtesy of Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

Around Oil, Static Time

From the experience of inter-species comradeship grounded in the first two points of our oil constellation, ammonites and vanvoorstia bennettiana, we move to the constellation’s third point, which holds the center of the installation and emphasizes the alternative experience of time inherent to the CICC (Figure 1). The audience builds out from a pentagonal shape where the CICC’s judges, prosecutors and witnesses will sit, surrounding a shallow basin of oil. The presence of oil here further asserts our distance from routine life. Through its aesthetic-conceptual use, the oil in the basin becomes alienated from its more typical resource consumption under capitalism. However, we should not forget the privilege inherent in bearing a conceptual, rather than physical relationship to oil. For species such as vanvoorstia bennettiana and activist collectives who will bring evidence to the CICC, including Indigenous federations from the regions around the Pastaza River basin, being pushed in physical proximity to oil has brought sickness and death.[13]

The basin brings the audience into close relation with oil, and – with an ammonite fossil placed within it – asserts the role of oil in climate colonialism and its connection to the erasure of deep time. I employ the term climate colonialism to foreground the deep ties between colonial and climate violence both historically and currently: in the colonialist power relations between countries of the Global North and South. Oil remains a material driver of these processes and arguably even instances of climate imperialism, thinking of the devastation caused to communities and marine life by the U.S. invasion and wars in Iraq. As discussed in the previous section, the intergenerational time frame of the CICC attempts to reckon with the entangled histories of climate and coloniality, but, beyond concept, how such a reckoning is constructed as a physical experience is crucial. How does the CICC enable a space of philosophical, existential questioning? Here I would like to focus specifically on how this is navigated within the CICC as a time-based performance.

The still, suspended quality of oil in the basin echoes another temporal layer of the court, specifically that of static, or durational, time as experienced by the viewer. The CICC hosts trials akin to political theatre. Beyond these trials, public programs will be organized around the themes of the exhibition, but the weight of the project lies in its activation as a site of prosecution. In this way, the ‘intended’ temporal experience of the CICC is durational, such that the audience will take part in lengthy court proceedings, witnessing and participating in turn.

Duration, as described by performance theorist Bojana Kunst in Artist at Work: Proximity of Art and Capitalism (2015), is experienced by the subject as static time. Kunst draws comparison with the experience of moving through the urban city; as the subject waits for a delayed train, they begin to recognize how they are moved, rather than moving, through daily life.[14] Static time, or duration, stands in opposition to the routines of movement in urban, capitalist life—as it prioritizes near-constant activity and work. Kunst further asserts that this slowing enables recognition of the control of chronologic time by structural forces: social, governmental, and economic. The static subject is thus dispossessed—opening new paths of subjectivity. Duration therefore functions in the vein of art’s capacity to interrupt sensibility (ways of seeing and meaning making), with the socially constructed sensibility figured here as chronologic time.[15]

Along with oil, we are set outside of capitalist time through the CICC’s durative, and artistic (‘other’) environment.[16] Following Kunst, this experience can potentially disrupt viewer subjectivity to reveal the controlled quality of movement and attention in social life, masquerading as free choice. Through such control, systems and institutions seek to orient subjects away from types of collective movement and attention which might threaten them. Stimulating a sort of stasis among an audience whose main task is to listen, the CICC accesses a dreamlike time in which threatened communities are centred, and forms of collectivity are practiced across species and time scales.

fig. 7-9 Radha D’Souza & Jonas Staal, ‘Comrades in Extinction’, Studies, 2020- 2021. Images courtesy of Jonas Staal. Commissioned by Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

Grief & Utopia

Oil in the CICC – manifesting across the constellation of the central oil basin, ammonite fossils, and extinct species such as vanvoorstia bennettiana – draws into relief both the experiences of layered temporality (intergenerational and static time) and of inter-species comradeship. This constellation represents the damaged ecology – reflective of our own global ecology – from where the CICC practices a form of utopian justice. Art historian Runette Kruger positions utopia as a tool for the “critical reappraisal of a given sociopolitical order”, activated through the ‘unrealistic’ character which defines it.[17] Utopia, understood through Kruger’s framing, can be politically engaged by working within and in response to socio political circumstances.

The CICC’s proximity to a real tribunal, emphasized by the prosecution of corporations and states for their actions by actually-impacted communities, functions as a critical distance – a point from which to imagine and take part in a reformulation of justice. D’Souza and Staal draw on the power of art to expand imaginaries by constructing an environment in which the audience can reflect on the limitations of legal systems, especially as they have been built to the benefit of corporations and states. The CICC’s appropriation of the form and script of the legal court functions as a utopic form of social critique of the legal system, enacted by adopting its forms and using them otherwise.

The tangible influence of this testing ground occurs through the heard testimony of the witnesses and the conclusions of the judges, which will be recorded and disseminated to institutions and activist organizations. But another instance in which the CICC actually enacts its idealism is in the re-archiving undertaken in Comrades in Extinction. Hand in hand with this re-ordering of memory, or the making visible of a network of comradeship, stands the CICC’s role as a site for mourning. The dead take their presence in the CICC through renderings of now extinct animal and plant species, as well as through stories of human witnesses present to speak for those already killed or who will be killed by climate criminal activity. D’Souza and Staal created this site, this proverbial cemetery, not to contrast our being alive with others’ lack of life but rather to assert our closeness to a similar kind of death – the death of extinction. This disorienting proximity prompts questioning: What will we learn from the deaths abounding around us? How might circumstances change if we held the lives and deaths of ‘othered’ human and non-human comrades differently? In recognizing how some bodies have been marked mournable and others not, we can constitute grief, especially when committed publicly, as a political act. [18] We see this differential distribution of grievability at work in the destruction of species. An at times passively noted trajectory, documented by species’ assessment notes in IUCN’s Red List:

The extinction of this species has been forecast since its discovery (Figure 4).[19]

Excitingly, D’Souza and Staal demonstrate that this trajectory can be effectively rewritten, offering a site in which to revise our understanding of climate crimes past and present, also as they impact future worlds. In this, the CICC poses the very real justice of a death that is seen, marked, mourned, and raged at. As this grief and rage push us toward collective action, they simultaneously function as vessels – embodied spaces through which we can honour and make present our comradely ancestors in a hopefully more just movement into the future.

– Read more about Kunstlicht ‘The Worldliness of Oil’ here.

[1] These quotes derive from the assessment notes of species in the IUCN’s Red List, which are compiled by various researchers. The species with these conservation notes or very similar include: 4639 (Figure 5), 30393 (Figure 9), 15187, 140414966, 140416686, 191546, 8891, 8706, 8888, 8128, 103192401, 1157, 39291, and 29488. These numbers are internal taxon IDs used by the IUCN, which lead to the assessment profiles of species on the Red List website (https://www.iucnredlist.org/).

[2] Radha D’Souza, What’s Wrong with Rights? Social Movements, Law and Liberal Imaginations (London: Pluto Press, 2018).

[3] The 85 species are somewhat randomly selected, but whether there is photo documentation of a species plays a crucial role. Additionally, the selection has tried to include a range of extinct species types. Supplementing its visual representation within the installation, Comrades in Extinction will also take the shape of a handout to be distributed to visitors and audience. The handout will provide a greater overview of the species in the archive, especially when and where they went extinct, as well as which threats drove their extinction.

[4] This article condenses (and deepens) the research analysis in my master’s thesis, which used the CICC as one of two case studies. Ashley Maum, “Heterotopic Ecologies: Art Exhibitions as Sites of Activist Intervention / Imagination,” MA Thesis, University of Amsterdam, 2021.

[5] It is important to acknowledge that I work within the research and production team behind the CICC. At the same time that this role makes my writing this article possible – it implicates me in the content of the project and my own perspective on it.

[6] Millar, A.J.K. (Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney, Australia). 2003. Vanvoorstia bennettiana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2003: e.T43993A10838671. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2003.RLTS.T43993A10838671.en

[7] Comrades in Extinction is an archive of 436 animals and 115 plants. Crucial to keep in mind is that this includes only extinct species for which there is enough data for an IUCN assessment to be completed. Thus, the number is not truly reflective of the scale of climate crisis-related species extinction.

[8] Radha D’Souza and Jonas Staal, CICC concept note, 2020.

[9] Emily Osterloff, “What is an ammonite?” Natural History Museum London, accessed 24 June 2021, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-an-ammonite.html.

[10] The translations of comrade have been undertaken with the help of philologist Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei in an effort to navigate the complexities of meaning across language.

[11] Jonas Staal, in conversation with author, 2020.

[12] Rolando Vázquez, Vistas of Modernity: decolonial aesthesis and the end of the contemporary (Amsterdam: Mondriaan Fund, 2020).

[13] Here I refer to the fight of the Pueblos Indígenas Amazónicos Unidos en Defensa de sus Territorios against the oil company Pluspetrol, for its pollution of the Pastaza River basin, which runs through Perú and Ecuador.

[14] Bojana Kunst, Artist at Work, Proximity of Art and Capitalism (Winchester: Zero Books, 2016), 60.

[15] For more on the sensible see: Jacques Rancière, “Foreword,” and “The Distribution of the Sensible: Politics and Aesthetics,” in The Politics of Aesthetics, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (London; NY: Continuum, 2004), 9-19.

[16] For more on the art space as ‘other’ see: Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité, trans. Jay Miskowiec (October 1984): 1-9.

[17] Runette Kruger, “Smooth New World: Agency and Utopia,” Culture, theory and critique 58, no. 3 (July 2017): 2.

[18] Judith Butler, “The Culture of Grief: Philosophy, Ecology and the Politics of Loss in the Twenty-first Century,” Online symposium by Aalborg University, 3 December 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0JBPQik2-x8.

[19] BirdLife International. 2018. Mitu mitu. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018: e.T22678486A132315266. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018- 2.RLTS.T22678486A132315266.en

- Tijdschrift Kunstlicht

Links

CICC / Ecologie / Kunst en Activisme /

Exposities

Expositie: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes

Een project van Radha D'Souza en Jonas Staal

Netwerk

Ashley Maum

Exhibitions and research

Magazine

Digitaal Archief: Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes