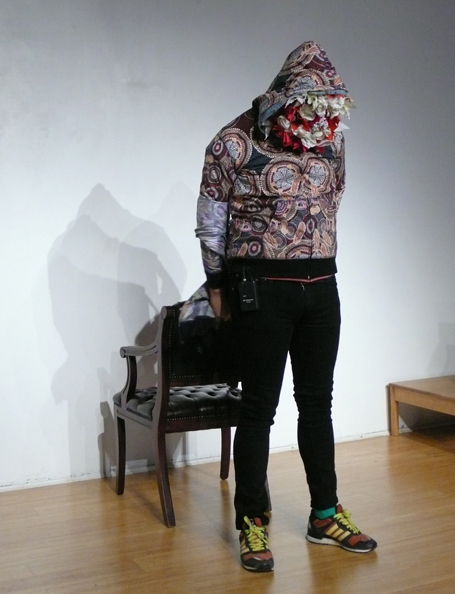

Performance van Christian Thompson tijdens de bijeenkomst 'Indigenous Art Now!'

Performance van Christian Thompson tijdens de bijeenkomst 'Indigenous Art Now!' Report: Indigenous Art Now!

Australians in London are not an uncommon sight, especially this summer when the cultural City of London Festival focuses on Oceania with different exhibitions and events throughout the London art world. One of the events coinciding with the festival took place in contemporary art gallery the October Gallery in Bloomsbury on June 28th: three contemporary artists from Australia and one from New Zealand discussed indigenous art and its reception in their homeland and around the world. The stimulating forum served to launch the new enterprise of Australian art magazine Artlink: Artlink Indigenous, an annual thematic edition recording and critiquing developments in indigenous art in Australia. The exhibition Current, showcasing six contemporary New Zealand artists, was another good reason to make your way to the gallery.

Indigenous Art Now! was the sequel to a successful event in May 2010 around the launch of the Artlink issue Blak on Blak. Then, Artlink, Framer Framed and AAMU – Museum of Contemporary Aboriginal Art joined forces in Utrecht to invite contemporary Aboriginal artists and various academics to talk about Aboriginal art. This time, the Australian artists invited to talk about their work were Fiona Foley, Vernon Ah Kee and Christian Thompson. James Ormsby, one of the Pacific artists from Current, also joined the debate. Heritage, landscape, self-representation, identity, (colonial) history and the (global) art world were the main topics of discussion during the afternoon. A responding panel consisted of writers, academics and curators from Australia, the UK and the Netherlands and was moderated expertly by journalist and Artlink guest-editor Daniel Browning. As he said in his introduction, his aim with the special issue is to ‘try and subvert old images that were constructed for Aboriginal people by others’. As he said: ‘we actively need to subvert false representations.’

Fiona Foley, well known for her public art – amongst other things – kicked off proceedings with a talk about her experiences in her commissioned work around Australia. With it she wants to address issues of colonial violence, history and dispersion ‘and to write Aboriginal people, Aboriginal culture, their references or historical lands back into the visual landscape.’

To get funding and public support for her work, Foley often chooses to not completely disclose the true nature of her work because ‘even though I’m speaking a historical truth, there is still a very dominant denial in white Australia about the history that has gone on before.’ Still, it is important for her to have contemporary histories and old histories intermingle and to put history in the public sphere. Talking about the six large art works that the regional town of Mackay commissioned from her, served to illustrate this: ‘I have this subtle hidden layer of meaning that I implant – even though you think ‘oh, that’s very simple work’, there are bullets melted into that metal wreath that people are still unaware of today.’

Another thing that illustrates the ongoing racial attitude is the fact that after vandalising of the art work – terrible in itself – a sign writer had to be flown up from Brisbane to work on restoring the piece (the fingerprints of Aboriginals on one of the sculptures). This all points to an ongoing racism and colonial attitude in the country, against which Foley feels she needs to fight with her art work. ‘As an artist, one of my roles is as an educator. And I get to use my art as a platform, to talk about this history and put it back in people’s faces about the brutality that they undertook to get rid of Aboriginal people of the land.’

Georges Petitjean, the curator of the AAMU and an admirer of Fiona Foley’s work, reminisced about the time when he studied in Melbourne and listened to reactions to her work ‘Lie of the Land’ outside the town hall from people on the tram. He recognises her experience that people do not truly know the complete history (or do not care), but also thinks it is good that through its public place the art work fuelled people’s thoughts and became part of institutionalised public art.

The second speaker of the afternoon, Vernon Ah Kee, also fights against the recurring pattern of racism and expresses his perpetual state of discomfort as a blackfella through his work. This outspoken artist makes large-scale drawings and text-based works dealing with the position of the Aboriginals in Australia. He does not see himself as the representative of all Aboriginals, but works from his own family and its history. The personal becomes political, even though he does not describe himself as a political artist. Ah Kee: ‘I know that that label has been ascribed to me, but it doesn’t fit. The work I make is about my family and about my family’s history, my own experiences. My family’s history is of dispossession, lots of violence and upheaval.’

James Ormsby, the New Zealand artist participating in the forum, is of Maori and Scottish descent and works from a research into history and forefathers – comparable to Ah Kee. His large-scale work Psaltearoa has influences from Scottish history and the colonial oppression in New Zealand. He says: ‘Love the thing that is most universal and therefore most personal.’ The universality of his art work is – in his view – considered normal in the New Zealand art world. Whereas in Australia the debate still rages on (self-)representation and authenticity of the Aboriginal artist, from Ormsby’s contribution this does not seem to be an issue in his country.

Of course this does not mean the topic of ethnic vs contemporary art is one that is not discussed in both countries. Ormsby belongs, as he says himself, to ‘the mob of Maori artists who don’t do spirals.’ This is comparable to the other topic Ah Kee brings up: the indiscriminate view of Aboriginal art in Australia. As an contemporary urban artist – like Foley and Thompson too – he is part of the East coast Aboriginal communities that form 80% of the population whereas the Aboriginal art (‘dot-dot’) that he is up against comes from the regional areas and comprises much less people.

‘We can talk about how Aboriginal art is part of Australian art. But it’s not. The main difference between Aboriginal art and Australian art is that bad art is called out for what it is, when we talk about Australian art. That doesn’t happen in Aboriginal art.’

In his thought-provoking talk, Ah Kee called for a serious critique of art. There is now only gushing praise which reduces everything to mediocrity. And we all are complicit in that because federal governments fund regional art centres (instead of investing in housing or health), but also because we all think of the regional art when Aboriginal art is mentioned, and museum collections also perpetrate that situation. ‘Aboriginal art is a kind of tulip mania.’ It seems that is why a serious reflection on the art as it is practiced in Artlink Indigenous is important to develop further. Only in that way can contemporary indigenous art play a part in the global art world. Ormsby concurred: ‘Culture shouldn’t be a backslapping exercise.’

The last artist to take to the stage was Christian Thompson, a contemporary artist who works with photo, video and performance. In his performance piece ‘Tree of Knowledge’, which included touching singing in Bidjara (the native language of his family), traditional music, crunk dancing and a long listing of all things Aboriginal – and therefore seemingly aspirational and good, he tried to bridge the gap between his Aboriginal identity and the universal values of the human condition. His undressing of layers of ‘ethnic’ clothing to a T-shirt with the British flag raised the question of what his identity really is. With the monotone voicing of all things Aboriginal, he connected well to the point made by Ah Kee about the indiscriminate praise for Aboriginal art.

This last topic was raised again in a round-table debate between moderator Daniel Browning and all the participating artists. It is up to the artists themselves to combat the stereotyping of Aboriginal art and be included in a wider global community. Because, as Thompson said: ‘Art is personal, it’s what people project on it that makes it political.’ Ah Kee added: ‘We shouldn’t overcome branding of the Aboriginal artist, but become the branding.’

The concluding debate also answered one of the main questions surrounding this launch of Artlink Indigenous: is such a special edition necessary in the critical landscape or should indigenous art not be put in a separate box? Although opinions differed, most argued that such a space is good. Not only does a dedicated edition work to prevent ‘inverse racism’ (all Aboriginal art is deemed wonderful and important because it has been made by Aboriginals and people dare not be judged as racist by saying something bad against it), but it also serves to show the diversity of Australian art. Whereas regional Aboriginal art has been subsidized by public funding and has become representative of all Australian art, urban contemporary indigenous art also needs to find its place in the art world.

And it’s not only an issue in the Australian (art) world but part of the larger post-colonial world, as art historian Dan Rycroft added: ‘it can be seen as part and parcel of a wider indigenous struggle that’s transnational. This is where the concept of transvangarde becomes quite resonant.’ The attention to ‘indigeneity’ as part of a larger global movement is a fact that Anthony Gardner, guest speaker at the launch, also is acutely aware of in his research into ‘biennalisation’ of the art world. He expressed the hope that this new enterprise of three annual issues of Artlink Indigenous will therefore contribute to a further understanding and development of relevant contemporary art critique in Australia and around the world.

Barbara Capel

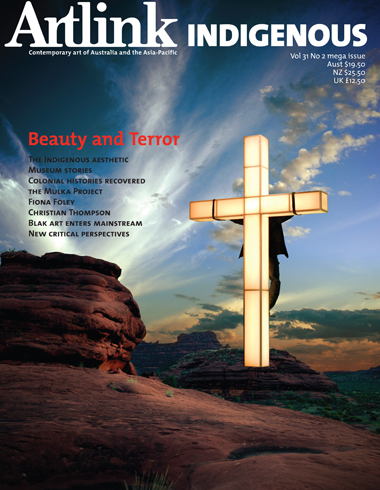

A summary of the panel discussion on the special issue Artlink Indigenous #1 Beauty and Terror, part of the series of annual issues on developments in indigenous art in Australia, organized in collaboration with the Australian contemporary art magazine Artlink and the October Gallery, London, June 28, 2011.

- AAMU - Museum for Contemporary Aboriginal Art

- ARTLINK INDIGENOUS #1 BEAUTY AND TERROR

- October Gallery - London

Links

Contemporary Aboriginal art /

Agenda

Indigenous Art Now!

Forum and launch for Artlink Indigenous.

Network

Vernon Ah Kee

Artist

Stephanie Radok

Artist, writer, editor

Natasha McKinney

Curator

Anthony Gardner

Art Historian

Daniel Rycroft

Art Historian

Christian Thompson

Artist

Fiona Foley

Artist, Curator