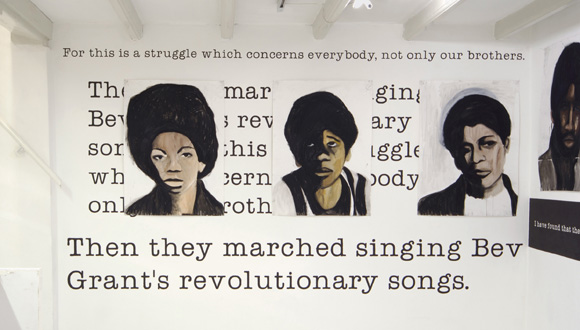

Iris Kensmil, Then They Marched (2008)

Iris Kensmil, Then They Marched (2008) Gerilja Talks: Nancy Jouwe x Black Women in the Dutch Arts Scene

On November 6, 2014, Gerilja Talks: Nancy Jouwe x Black Women in the Dutch Arts Scene was the first talk by gerilja/kurating magazine (G/K) at Framer Framed. Chandra Frank and Sarah Klerks, the founders of this new online magazine, are interested in the status quo of black women in the Dutch art scene. Along with the magazine, associated talks will be organised to discuss in depth issues about art, race and gender.

The speaker of the very first talk was Nancy Jouwe. Jouwe co-edited the book Kaleidoscopische visies: de zwarte, migranten en vluchtelingen-vrouwenbeweging in Nederland (ed. Maayke Botman, G. Wekker, Nancy Jouwe, 2001), which deals with issues of black women in the Netherlands. Jouwe’s talk gravitated around this publication. Jouwe wanted to write the book Kaleidoscopische visies because of an aspiration to be more informed about the position of black women in the Dutch society. At that time, Professor Gloria Wekker was a teacher at the University of Utrecht. Jouwe, Wekker and Botman conducted research in the archive of ATRIA focusing on performing arts and literature due to their interrelatedness. Her talk at Framer Framed, however, focuses on the visual arts as well and focuses on the contribution of black women to the arts scene from the ‘60s till the ‘90s, it, nonetheless, appeared to be that they were considerably unrepresented during the first two decennia. The women who did enter the white male dominated realm brought with them their body politics, new stories, and created new audiences. The arts domain and its audience were very white at that time.

Jouwe introduced her view on women of colour in the Dutch art scene by discussing two historical images that depict black women. The way these two art works have been researched by art history scholars is exemplary of the presence of black women in art history. They were considerably depicted as servants or slaves. During art history classes, moreover, students where advised to skip the chapters concerning non-western art. The most striking of the two examples is The Four Continents (c. 1614) by Peter-Paul Rubens. It is an allegory of the four continents ‘discovered’ by the west. In the middle there is an Ethiopian woman who stands out due to this central position. According to Jouwe, the man on the right is Moses, and the black woman in the centre is his first wife.

During her presentation Nancy Jouwe commemorated numerous black women who contributed to the arts scene in different ways in different areas. Thea Doelwijt is a writer and playwright who started to work in Suriname. In 1982, she wrote a play inspired by Sophie Redmond’s book A fat black woman like me. The story unravels chronicles of a black woman in Suriname and is considered very adamant. Another writer is Sylvia Pessireron from Maluku descent. She feared the way Maluku were treated in Dutch society. With her activities as an activist, she gave a voice to the experiences of children from Maluku immigrants. Most of the latter were soldiers in the colonial army in the Eastern Indies. Herewith, she represents trans-generational trauma from parents to children. Jill Stolk’s work addresses comparable themes – her parents were in the Japanese camps in Indonesia.

Astrid Roemer, Marion Bloem and Joanna Werners made important contributions to this group of writers as well. Roemer wrote in a lyrical style, which was not present beforehand. Bloem is a second generation Indo-European and is considered an influential documentary maker. Werners, on her turn, gave a voice to lesbian sexuality in the Dutch black art scene.

Jouwe continued her story with an enumeration of black female performers and presenters. Wieteke van Dort, for example, did a stereotypical character of an Indonesian aunt. Despite of this stereotyped character, some Indo-Europeans seemed to appreciate this representation on television. Gerda Havertong, an actress and singer of Surinam descent, is well known for her role in the Dutch Sesame Street in particular.

The most important filmmakers and visual artists are Francis Vrij, of whom many films have been shown at the Dutch film festival; Fatima Jebli Ouazani made poetic work, which was also shown at the festival; Meral Uslu, a documentary maker and screenwriter; and Fiona Tan, both filmmaker and visual artist. Iris Kensmil and Natasja Kensmil form part of this group as well. Both are visual artists, whose paintings have been exhibited in the Netherlands and internationally. Most of their works revolve around slavery.

The visual artist Patricia Kaersenhout was present in the room and she spontaneously elucidates her work, which focuses on identity and postcolonial stories. Kaersenhout was the leading force of projects on Surinam artists living in Europe and in Surinam. One project resulted in a show at Fort Zeelandia and in the first publication on Surinam artists called WAKAMAN: drawing lines – connecting dots (2009). Her work has been on show at Framer Framed as part of the Embodied Spaces (2015) exhibition curated by Christine Eyene.

Jouwe pointed out the contribution of several other artists to this scene, among others Sara Blokland. Sara Blokland works with photography and video, thereby exploring the presentation of families put in a postcolonial perspective. She was awarded an art prize of the Mama Cash women’s fund and is founder of UNFIXED: Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art. Esiri Erheriene Essi lives in Amsterdam and London and her highly political work revolves around racism and sexism. Essi was the first black woman who had a solo retrospective in a Dutch museum, namely Museum Arnhem. Jouwe did a speech at the opening of the show; Jouwe notes they were the only black women in the room. Last but not least, Jouwe points out Ebere Groenouwe’s show in a gallery in Utrecht.

During the discussion, Sarah Klerks raised the question why the term ‘black’ was used by some artists in the book (‘zwarte’ vluchtelingen en migranten vrouwen was the term deployed in the book). Jouwe pointed out that ‘black’ as a political term was used to acknowledge the shared histories and daily lives of women who faced institutionalized and everyday racism. In this sense, using the term ‘black’ in the Dutch ‘post’-colonial setting, can be used to unite women of different ethnicities to talk about the implications of racism. However, using ‘black’ to refer to themselves did not count for all women. Some women identified more with the term ‘migrant’ and others more with the term ‘refugee’ (vluchteling). Due to this diversity the term ‘zmv’ is central in the book.

Text by Léon Kruijswijk,

Framer Framed

- UNFIXED PROJECTS

Links

Feminism / Suriname /

Agenda

Gerilja Talks: Nancy Jouwe x Black Women in the Dutch Arts Scene

On the valuable contributions that Black women have made to the Dutch arts scene.

Network

Iris Kensmil

Artist

Chandra Frank

Curator and PhD Candidate

Sarah Klerks