Spaces of Belonging for Undocumented Migrants

Questioning who you are, and where you belong, affects everybody’s life. However, undocumented migrants experience the construction of belonging in a more intense and acute way. In Europe, they are increasingly stigmatised and excluded through dominant discourses, and in everyday encounters. Due to their undocumented-ness and exclusion, they form a marginalised and rather invisible group in the host-society. Often, they are represented by others instead of being given the space to represent themselves. As a result, little is known about how they construct a sense of home away from home and seek for recognition and inclusion both on a state-level, and through people and places they encounter in their everyday life.

This article discusses the main research findings from a master thesis study at Framer Framed on the Amsterdam-based art collective We Sell Reality to shed light on experiences of, and strategies to construct, a sense of belonging among undocumented migrants. The study is conducted in 2021 as part of the master’s program Urban Geography at Utrecht University. For three months, participatory art-based methods were implemented during art workshops. Besides, brainstorm sessions and in- depth interviews were conducted.

Text by Carola Vasileiadi

May 2022

Experiences of (non-)belonging

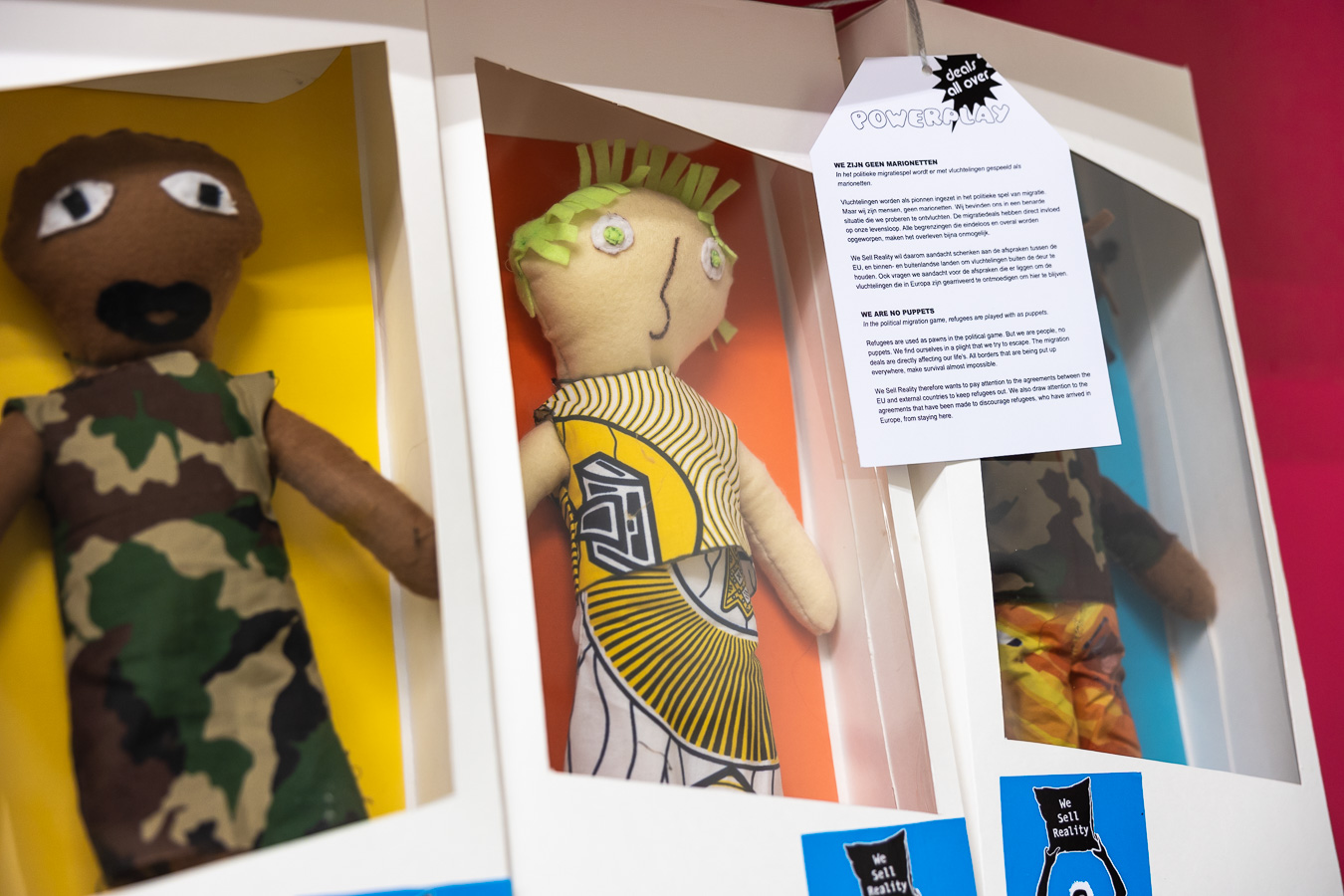

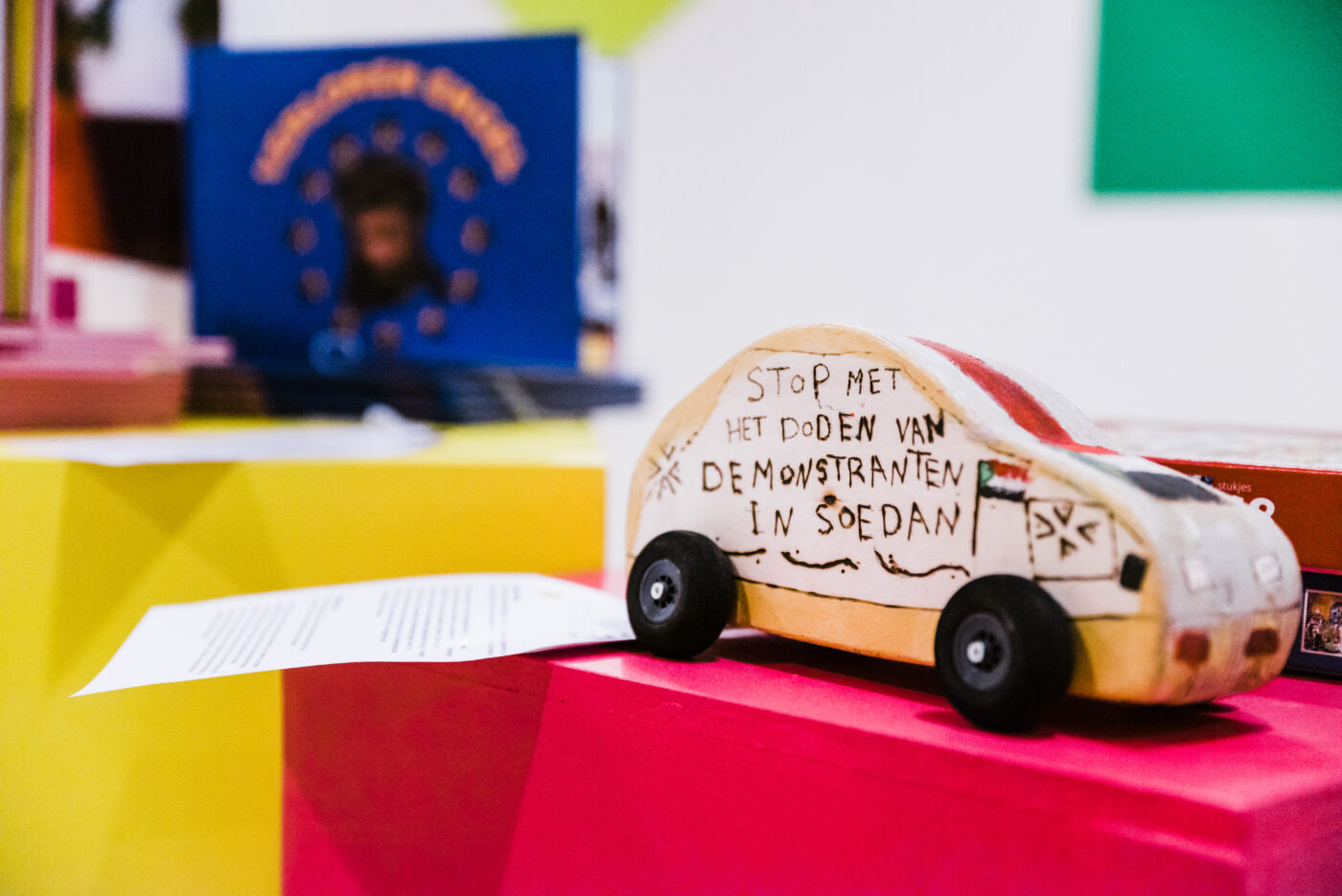

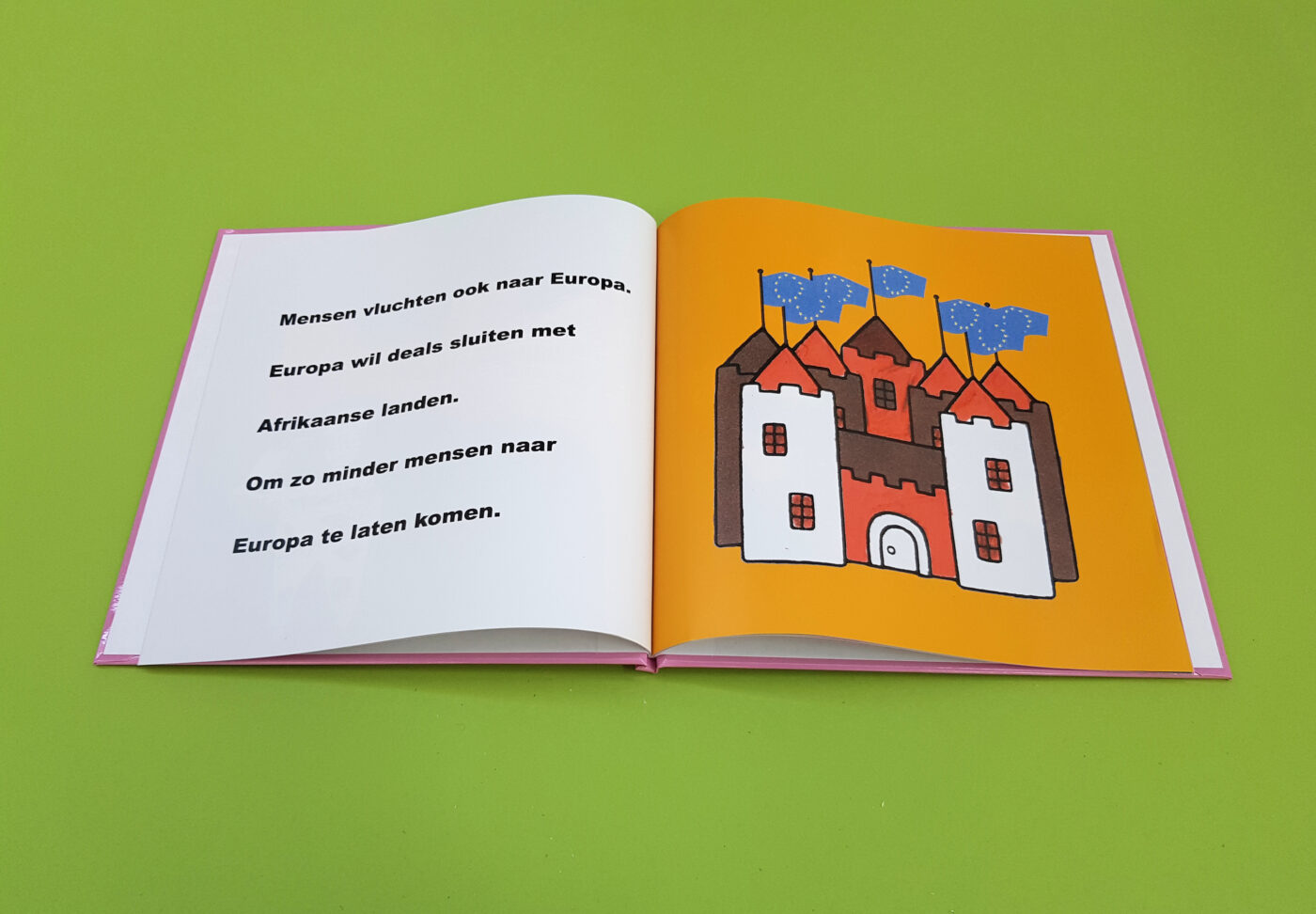

We Sell Reality reflects upon the societal context in which they find themselves, and how this impacts their experiences of belonging. Over the last decade, western society has reported a ‘refugee crises’ to stress the increasing migration flow of forced migrants towards European countries. Declaring a ‘crisis’ problematises this type of migration and implies that it must be monitored, regulated and reduced. European countries implement national and international strategies to exclude forced migrants and discourage them to migrate to its nations. Besides, they make push-deals between countries to strengthen their territorial borders and regulate the freedom of movement of certain people across their borders. These migration policies are experienced as extremely frustrating and dehumanizing because they brand forced migrants as unwanted and exclude them from society. As a result, a strong sense of non-belonging in the host society arises. The collective critically reflected upon the migration policies through their art exhibition Powerplay – Deals All Over (We Sell Reality, September 2021).

The notion of non-belonging is emphasised through experiences of the asylum procedure in The Netherlands. Forced migrants are treated badly by the Dutch migration system and experience the asylum process as very exhausting and sometimes even traumatic. Some artists feel not assisted throughout the procedure and completely abandoned by the system. One states that his lawyer was not on his side and repeatedly told him that he is not allowed to stay in The Netherlands. Another believes that the government has a hidden agenda to make their lives difficult so that they would voluntarily leave the country. The procedures are taking years of waiting while they feel treated as being ‘stupid’, ‘less’ and not worthy of a citizenship status. It is assumed that when the IND (Dutch immigration service) wanted to offer asylum, they could do it, but they simply chose not to.

Due to the migration policies of the EU, many forced migrants who apply for asylum do not get citizenship rights in the host country. Consequently, there exists a respective group of undocumented migrants. Whenever an asylum application is denied, one cannot stay in the country. However, some undocumented migrants do not leave immediately in the hope to get accepted when they try again or find other routes to seek asylum. Others decide to stay without documents. Because they are not recognised as a citizen by the state, they live with the risk of being arrested. They can be sent to detention and ultimately, they can also be deported from the host country and sent back to their country of origin. This is problematic, because they can be refused when they return, or even being killed. They are stuck in limbo between their country of origin and the host country. As a result of their exclusion from society, lack of possibilities to integrate, and not being allowed to work, a problem of homelessness among undocumented migrants arises. Many end up on the streets and face difficulties, stress, and issues regarding their mental health.

Undocumented migrants are often negatively represented through dominant discourses, which further accentuates their sense of non-belong. In the media, they are portrayed as ‘liars’, ‘criminals’ and as a threat to European culture and society. These labels present just some examples of the exclusionary practices that reinforce fear and hostility of citizens towards them and serve to legitimize their exclusion. This is also reflected in the everyday life of the artists, in which they are confronted with racial and stigmatizing incidents. For example, when migrants are rejected asylum in the Netherlands, people assume they are ‘illegal’ and must leave the country. However, a person cannot be illegal, and this label denies their humanity. It is misleading to suggest that undocumented migrants arrived without a valid reason just because they do not have documents or are out of procedure. Besides, people believe that they migrated for economic reasons, while this is a huge misperception of their situation.

Remarkably, the collective experiences a great difference between belonging in small towns and villages, and in urban areas. On the one hand, they share negative stories about people they encounter in villages. For example, an artist encountered a man who told him a major part of migrants want to do nothing, take money from the government, and stay at home while people in the city would never talk like that. Besides, in small towns, people hold more stereotypical thoughts and immediately expect the artists to be refugees. On the other hand, Amsterdam residents are less likely to label and exclude them and are more positive towards welcoming them into the city. They are minding their own business and do not mind their presence. All artists feel more comfortable, safer, and prefer to live in the city. This comparison presents that how one is welcomed and positioned by others in particular places have a strong influence on feeling included and belonging within that place.

Creative Strategies for Political Belonging

Reflections on the societal context in which the members of We Sell Reality find themselves mainly shows experiences of non-belonging in the host society. However, We Sell Reality demonstrates how art practices can operate as an alternative, creative strategy to construct a sense of belonging within an excluding society. While undocumented migrants are constantly forced into a position to say; ‘sorry that I am here’, the collective does not excuse itself and makes unapologetic and strong work that can be characterised by colours and lightness against a deeper layer of heavy, touching and confronting political messages. Their practices transcend barriers of nationality, citizenship status and cultural differences through which they can politically represent themselves, state their rights and speak back to exclusionary discourses. This appears to form a key element to construct a sense of political belonging.

The collective does not only reflect on their lived world, but represents the experiences of a larger group of undocumented migrants in European countries. Through their art, they send a political message that speaks for many unheard migrant voices. The critical reflection that is communicated through their art contributes to new forms of knowledge and provides great opportunities for their audience to better understand their daily lived world. The hope for recognition and inclusion in the Dutch society that is generated through these practices must not be underestimated. The artists believe that by becoming more visible and sharing their experiences through their own narrative could humanise the inevitable flow of migration and strengthen national and local hospitality towards them. They hope to influence the mindset of migration policymakers, for them to be more open to accepting refugees and construct policies in such a way, that it has a more positive impact on their lives and sense of belonging in the host society.

We Sell Reality focuses on their creative development and ambitions in the arts, which contributes to their empowerment and growing confidence as artists. Some members are better at doing research and interested in political topics, while others are more interested in exploring different art techniques. While the members are discovering their potentials and strengths within the arts, they are no longer framed as ‘undocumented migrants’ or ‘forced migrants’. The development of their individual qualities opens possibilities to identify themselves as artists, or simply just as human beings having fun together. The study on We Sell Reality thereby beautifully reflects how artistic practices support the agency of marginalised groups to reconstruct their identities and narratives in a playful and accessible way. Taking agency in identifying the self, against how one is labelled and stigmatised by others, contributes to improving one’s social position in society towards a more humanised identity.

Creative Spaces for a sense of Belonging in Place

Besides, the political relevance of their practices, being part of We Sell Reality contributes to constructing a sense of place attachment in the city. This emotional and personal feeling of being at home in Amsterdam arises because the artist find support by the collective that indirectly serves to make friends. The artistic community originates out of people that suffer from the same circumstances and fight for the same goals. Through their common lived world and shared interest in making art, the members feel at home and like they belong to each other. The group provides a safe space to share personal situations, experiences, memories, and worries, but also very light and funny stories. The social importance is emphasised because the artists do not only meet to make art, but also outside working hours. They did the Ramadan and iftar together and celebrated Eid Mubarak (the end of the Ramadan). Besides, they often organise fun events like dinners, parties, and a barbecue in the park.

The art practices in itself also play a significant role in constructing a sense of belongingness in place. By indirectly providing the opportunity to share, sometimes traumatic, experiences through their practices, improvement of their mental health is supported. Exemplifying, commissioned by the music festival in Het Bimhuis, the collective worked with an infrared camera to highlight the chances of forced migrants to successfully cross the European borders. During this project, the artists were laughing and having fun together while directing others how to act in front of the camera. Their creative ideas, however, were based on their own experiences of hiding in a truck on their way to the UK. This project illustrates that they share lightness and joy together despite the deeper layer of heavy stories they carry with them. The safe space for reflection within the collective creates opportunities for a sense of feeling comfortable and at home.

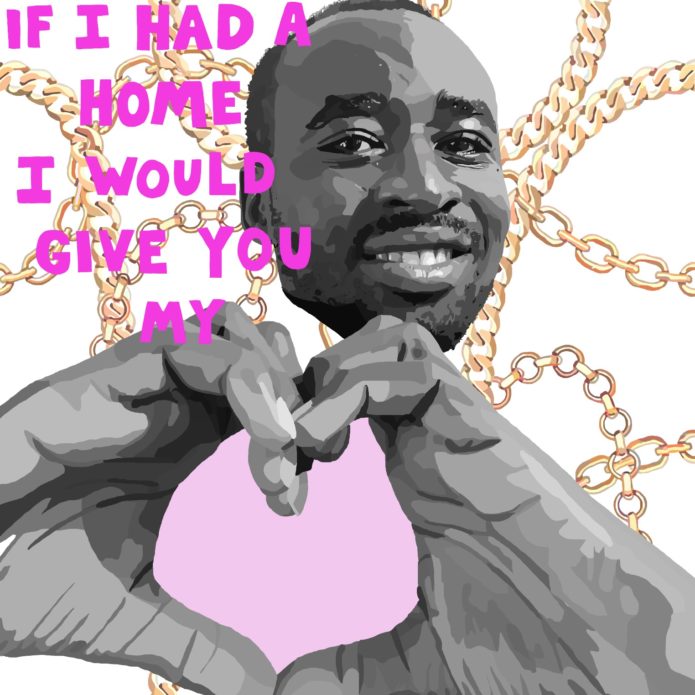

Collage of the collective, made by We Sell Reality

Furthermore, through joining the art collective, opportunities arise to do something meaningful in the everyday life. The importance of having an activity in the city and feel productive especially counts for undocumented migrants as they are constantly waiting during their asylum procedure and not allowed to work. We Sell Reality gives a reason to wake up and go out of the house. The extent to which the collective appreciates having something to do in the place they currently live present the importance of everyday life activities to construct a sense of belonging. Thereby, the artists express how much they appreciate the flexibility in working with We Sell Reality. The professional artist they work with is not forcing them to work, which makes them feel like they do it voluntarily. They experience agency in deciding if they want to work, and which specific practices they wish to do, without feeling pressure. This makes them feel comfortable, like they can be themselves, and at home.

Framer Framed as a Cultural and Artistic Space for Belonging

Although We Sell Reality works independently and the agency of the collective is highly respected, Framer Framed assists when needed in organizing their exhibitions, sharing recourses, materials, and building a social and artistic network in the city. When their exhibition ‘Powerplay – Deals All Over’ ended, Framer Framed and We Sell Reality continued their collaboration as both value building and maintaining a long-term relationship. The collaboration is not based upon a pre-defined and time-set plan but adjusted to opportunities that appear, ideas that arise, and by providing available recourses that are needed at the time. Framer Framed as a cultural and artistic institution in the city offers a platform of opportunities for the undocumented migrants to influence the exclusionary migration system from a bottom-up approach. Thereby, the study sheds light on the importance of inclusive, creative places in the city in supporting the construction of a counter narrative on undocumented migration while they are being politically excluded by the migration system of the state.

Starting from Framer Framed as a political and creative platform, We Sell Reality builds a network in the city and collaborates with several city-based museums and powerful institutions. Within these places, they are not approached as visitors or helpless victims but as powerful and inspirational artists. The collective feels that their existence and contested position in society is acknowledged by these institutions and that their stories are heard, recognised and important. Through this welcoming approach, opportunities respectfully arise to work on artistic projects together. The study hereby showcases the role of Framer Framed in connecting and integrating marginalised groups in the city while serving as a safe space for emotional and political support. It manifests the relevance of artistic and cultural spaces in collaboratively serving as humanitarian actors to build inclusive communities and places of belonging in the city. These places could lead to the humanization of undocumented migrants, strengthen national support towards them, and open possibilities for societal inclusion and political belonging on a state level in the future.

Community & Learning / Action Research / Migration /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Homies

Exhibition and clothing shop selling a fashion line produced by members of the art collective We Sell Reality

Exhibition: Powerplay – Deals All Over

A colourful installation by collective We Sell Reality

Agenda

We Sell Reality: Sudan

A get-together in solidarity with the protests in Sudan

Opening: Powerplay – Deals All Over

With We Sell Reality and DJ Crazy

Network