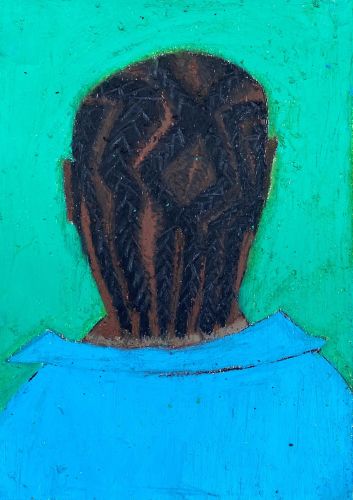

Kenneth Aidoo, 'My hair is versatile' (2021), courtesy of Galerie 23

Kenneth Aidoo, 'My hair is versatile' (2021), courtesy of Galerie 23 De indringende oliepastel portretten van Kenneth Aidoo

There is something incredibly captivating about the oil pastel portraits of Amsterdam-based artist Kenneth Aidoo (1988). Using bright and predominantly primary colours, the artist not only paints portraits of icons and personal heroes such as Jean-Michel Basquiat and Yaa Asantewaa, the Queen Mother of the former Ghanaian Ashanti Kingdom he also pays tribute to individuals whose stories often remain untold. Take the Black soldiers who fought in the Second World War, for example, but have remained more or less invisible in the post-war narrative.

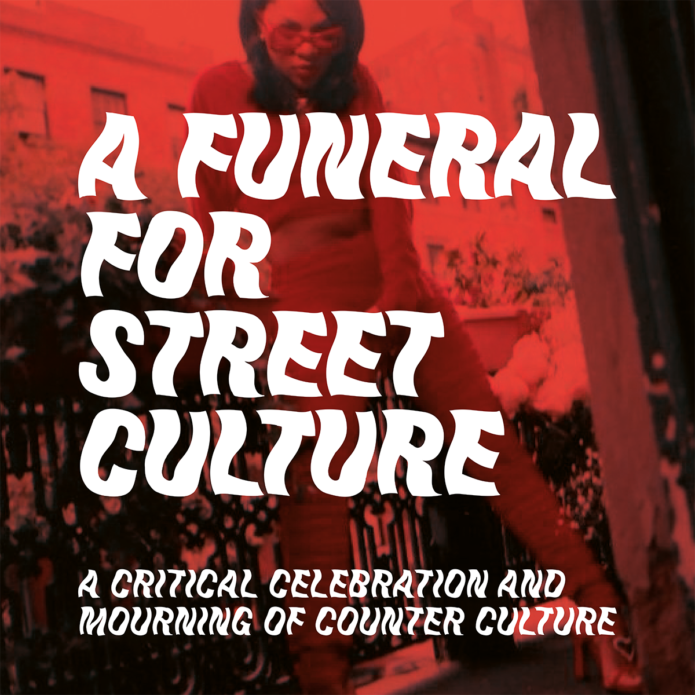

Aidoo is one of the participating artists in the group project A Funeral for Street Culture by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo, where a small selection of his paintings are on rotating display. Below he tells us about taking pride in your roots and how he found a creative community of likeminded people.

by Rolien Zonneveld

July 2021

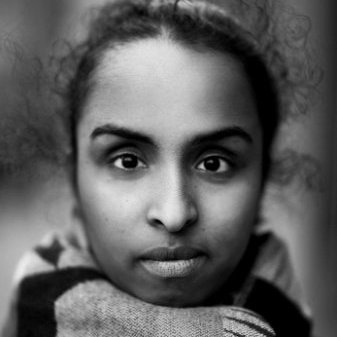

Kenneth Aidoo in front of his work Yeshua embracing Emmett Till and Trayvon Martin at A Funeral for Street Culture. Photo © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

Painting has never been the core medium of artist Kenneth Aidoo. In fact, he initially set out to study screenwriting at the Film Academy, but he later transferred to Amsterdam’s Gerrit Rietveld Academy. In the department of audiovisual art, he continued to experiment with film before changing to pastel paintings for his graduation.

Since then, he has produced a significant and ever-expanding body of work. “At the moment I am preparing for a new series for which I am delving into Black figures in European history,” Aidoo explains. Here he focuses on people that have played an important role on the world stage but whose stories are not necessarily part of the canon. He lists St. Maurice as an example: a mystical commander of the Theban Legion in the late third century, who throughout the centuries has been depicted as a Black African dressed as a Roman soldier – an unusual combination.

Whether St. Maurice actually existed is being questioned to this day but one thing is certain: he really appeals to the imagination. “I like to do research on these figures, but then let my fantasy take over,” he continues. In practice, this means that he infuses his paintings with some literal historical references but also adds some elements that spring from his own mind. As a result, hybrid non-fiction fantasy figures emerge. “For me it’s a way to dream about a pre-colonial Europe not yet tainted by racism,” he explains. “I fantasise about what they may have looked like, what they dressed like. I see it as a time in history where Black people could aspire to become whoever they wanted to be.” It’s almost as if by fusing all these elements Aidoo writes his own version of history – creating a more idealistic, romanticised version of society.

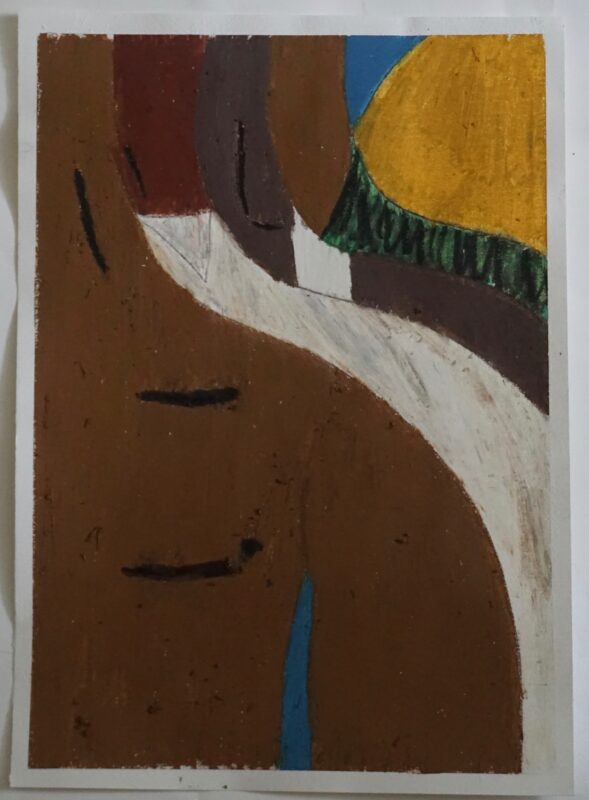

Kenneth Aidoo, Under an umbrella

Aidoo himself was born and raised in Amsterdam but has roots in Ghana, where both his parents are from. His Ghanian descent is also one of the recurring themes in his work. An example can be seen in his series around the cloth ‘kente’, a royal fabric which has its origins in the Ghanian town Bonwire. “I have a great love for kente,” Aidoo explains. “The legend goes that two weavers saw a spider spinning its web in a unique pattern and took the technique from it to begin and form the birth of kente. The cloth comes with a lot of symbols depicting the character or the status of the person wearing it. Kente as an attire has many cultural connotations, not just for Ghanaians but for a lot of people within the African diaspora.”

This preoccupation with the diaspora also emerges in the video work Displacement, which was part of an assignment for Rietveld. For this project he travelled to Suriname – a place he has felt a sense of connection to ever since he was a child. For him, it always felt as if he shared the same ethnic background as the Surinamese friends he grew up with. By visiting Suriname, while simultaneously delving into the painful chapter of the trans Atlantic slave trade between Ghana, the Netherlands and the Caribbean, Aidoo realised he was actually examining his own sense of belonging.

Kenneth Aidoo, First things first. I am black

Lately Aidoo increasingly finds himself surrounded by like-minded artists, who – like him – explore the positions of Black people in society through their art. Take 25-year-old Iriée Zamblé for example, who Aidoo has done multiple group shows with and who paints dignifying images of everyday Afro-Dutch people. Or Bodil Ouédraogo, whose work is also on show in A Funeral For Street Culture and who graduated from Rietveld in the same year. Both her and Aidoo’s work centers around their bicultural identity – Bodil Ouédraogo has investigated the relationship between ‘Black hair’ and identity, among other related topics – so it was only a matter of time that they would find each other artistically. “But it’s not only Bodil who I consider my peer, it is also Rita Ouédraogo and Amal Alhaag – the curators of A Funeral For Street Culture – that I feel inspired by, and Wes Mapes, who is also part of the show.”

Judging from Aidoo’s words, a community of artists truly seems to have been forged – one that will continue far past Framer Framed’s walls.

Kenneth Aidoo, Yeshua embracing Emmett Till and Trayvon Martin

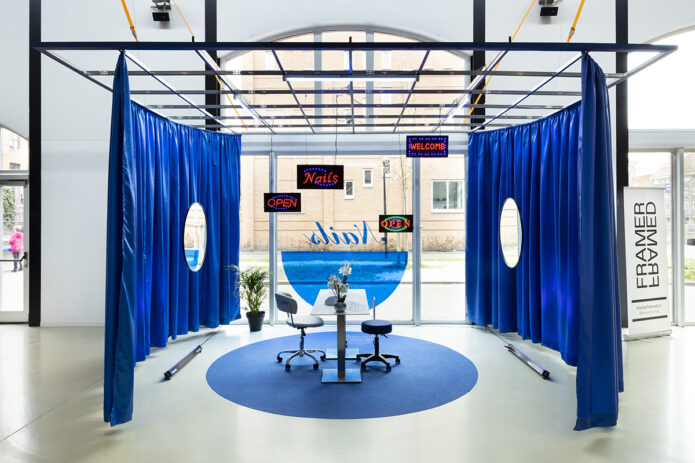

A Funeral for Street Culture is an ongoing project by Metro54 and curator Rita Ouédraogo, hosted by Framer Framed.

Exposities

Project: A Funeral for Street Culture

Een groepsproject van Metro54 en Rita Ouédraogo gehost door Framer Framed

Netwerk

Bodil Ouédraogo

Kunstenaar

Kenneth Aidoo

Schilder en filmmaker