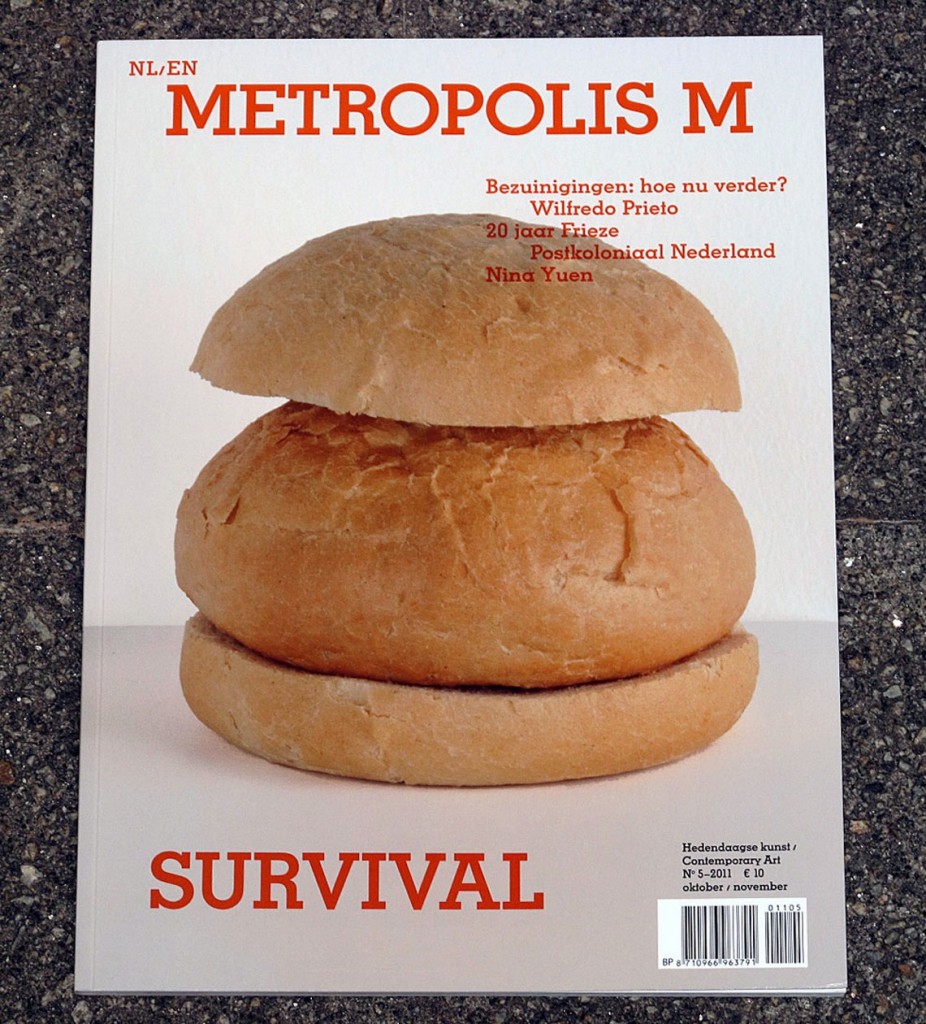

Metropolis M, Survival (n.5 2012)

Metropolis M, Survival (n.5 2012) The Netherlands in Post-Colonial Perspective

Compared with other European art institutes, those in the Netherlands lag behind in processing their nation’s colonial past. There may be more exhibitions of non-Western art, but they are rarely about the Dutch colonial past and its after-effects. Projects by Framer Framed, SMBA, De Appel, and others hope to change that.

Although there have been postcolonial discourses in the world of art in such countries as France and England for some time, in the Netherlands it has been relatively quiet. There are some tentative signs that this is changing, but art historical research and art institutes have so far given the subject little attention. While it is true that exhibitions of art from the former colonies are held with some regularity, including Beyond the Dutch at the Centraal Museum in Utrecht in 2009, which investigated mutual influences between the Netherlands and Indonesia during and after the colonial period, and Paramaribo Perspectives at TENT in 2010 in Rotterdam, an exchange between Surinamese and Dutch artists with several Rotterdam institutes taking part, these exhibitions have not really demonstrated a postcolonial perspective. Moreover, the approach goes no further than an incidental reconnaissance that does not invoke any structural changes in exhibition policies.

In the absence of any new perspective, the ethnocentric view has been the determining factor in presenting non-Western art, while integration of art from previously colonized countries never occurred. We can only guess at the reasons. It can in part be explained by the fact that the Netherlands as a society has rarely taken on the confrontation with its colonial past. As a nation, we seem to have difficulty looking at the dark sides of our past, so that the debate continues to stagnate in shame, guilt and even nostalgia. The average Dutch citizen knows very little about the role the Netherlands played in slavery. Schools barely touch on the subject, and the Dutch East India Company is primarily seen as the enlightened example of progressive Dutch mercantilism. There is Keti Koti, an annual remembrance of the abolition of slavery, but even though that period lasted far longer than World War II, it is not a national commemoration.

That something is going on under the surface can be seen in controversies over the erection of commemorative monuments, which flare up and disappear just as quickly without finding a place in a broader social dialogue, or the taboo on mentioning that the popular Zwarte Piet (Black Pete) is the black servant boy of a white Saint Nicholas. A protest march organized during the Be(com)ing Dutch exhibition at the Van Abbemuseum was cancelled under the pressure of threats. A publication such as Postkoloniaal Nederland, by Gert Oostindie, presented in 2009 as an initial investigation into this subject (which says a great deal in itself), concludes that postcolonial communities let go of their roots more quickly in the Netherlands than they do elsewhere. As the author claims, the debate about citizenship is about other concerns, especially Islam, and postcolonial history is a closed book before it has even been properly written.

World Art

While there has been barely any confrontation with the colonial past, it is already being dismissed as an out of date topic. However, the recent debates about globalization and integration are precisely what should be enriched by a critical postcolonial attitude that recognizes the important extent to which our (view of the) world is still determined by the colonial legacy. Traces of colonialism are still to be found in such institutes as museums. The art museums, based on a Western idea of art, are primarily concerned with European and North American art, while museums of anthropology and ethnology concern themselves with non-Western cultures. They form two sides of the same coin, one that is rapidly losing its validity in today’s global developments. Nonetheless, in the Netherlands, the initiative for the discussion about the postcolonial condition is primarily being raised by the museums of ethnology. Initially founded in order to display the cultures from the colonies, they are now under more pressure to prove their contemporary social relevance. Most museums of ethnology have by now transformed themselves into museums for world culture, in which primitive, fossilized cultures are exhibited in a changing contemporary perspective.

One important step in this regard took place in 1985 at the Tropenmueum (Tropical Museum) in Amsterdam, with the debate on Moderne Kunst in Ontwikkelingslanden (Modern Art in Developing Countries). The intention was to induce ethnology museums and art museums to work together in presenting non-Western, contemporary art. This was a few years before the Paris exhibition Magiciens de la Terre (Magicians of the Earth) caused a commotion around the globe. Despite criticism of its ahistorical and decontextualised presentation in which ritual objects and autonomous artworks were displayed side by side, this exhibition became the standard for the presentation of world art.

Some things did happen in the Netherlands after that, although they reached no further than incidental explorations. Interesting examples include Heart of Darkness (Kröller-Müller Museum, 1995), which with works of art from all corners of the world showed how the Western art idiom is transformed when it is applied to local stories, or Unpacking Europe (Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, 2001), in which artists with non-Western backgrounds were invited to look at Europe as ‘the Other’, in order to play the dominant heterogeneous image of Europe and the contrasting, hybrid postcolonial reality against one another. But recent years have mostly seen the organization of many blockbusters, such as Brazil Contemporary (2009) and China Contemporary (2006) at the Boijmans Van Beuningen, or Cuba! (2009) at the Groninger Museum, which, with their geographic themes, have remained stuck in an exoticism that feels almost colonial in nature.

Museums of art and ethnology are growing closer to one another in terms of their presentations of contemporary non-Western art. Ethnology museums are presenting collections in an increasingly autonomous fashion in order to suggest a world culture in which everything can be connected together aesthetically, while in the art museums we see an emphasis on an ethno-geographic orientation in which artists are asked to express their identity in a static way. Even if these exhibitions contribute to putting world art on the map, the distinction between Western and non-Western art is not really an issue for discussion, and no new proposals are being made about what a true postcolonial exhibition practice might entail.

For Meta Knol and Lejo Schenk, directors of De Lakenhal Museum in Leiden and the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam respectively, the absence of any current postcolonial debate amongst museums was the motivation to publish an opinion column in early 2010 in the NRC Handelsblad newspaper, entitled ‘The Distinction between Western and Non-Western Art is Out of Date’. They claimed that ‘the Dutch museums finally need to be freed from their colonial relationships’ and argued for more debate between art museums and ethnology museums about the presentation of contemporary world art, aiming towards the development of a global exhibition practice.

Meta Knol had previously been involved in the founding of the discussion platform Framer Framed, which has grown into a broad, nationwide collaborative effort between ethnology museums, heritage institutes and art museums. Nonetheless, according to Cas Bool and Josien Pieterse, founding directors of the platform, most of the interest still comes from the ethnology museums, although art institutes have recently been showing more interest.

In Amsterdam, Jelle Bouwhuis of the SMBA is trying to get the Stedelijk Museum into motion with the programme 1975. For a period of two years, its focus will be on the relationship between contemporary art and post-colonialism. Global themes such as migration, geopolitics and identity will be looked at in a series of exhibitions, debates and events. It also includes a planned collaborative project with the Nubuku Foundation of Accra, Ghana.

It is striking that 1975 – despite the fact that the title emphatically refers to the independence of Suriname, and consequently the year the Netherlands became a postcolonial society – seems to have less of an eye for what post-colonialism means for the Netherlands’ own colonial past. According to Bouwhuis, this is because our postcolonial relations are more concerned with Africa than with our former colonies. Internationally, Africa is the figurehead of the Third World, where most of the development aid goes, and it is moreover the new hot spot in the international art world. But is that fact – that we always prefer to look to other countries – not the very reason that a postcolonial reflection on our own history does not occur?

The strength of 1975 lies in the long period of time during which the postcolonial condition will be looked at from different perspectives. Nonetheless, a thorough investigation of the implications of our own colonial history is needed. Such an investigation might be expected from Michael Tedja’s participation in the residency programme BijlmAIR, or the symposium being planned to look at the impact of colonial ideology in contemporary exhibition practice. According to the organizers of 1975, it is too early to say whether the project will lead to a debate in the museum that will examine their own collection and exhibition policies from the perspective of postcolonial criticism.

Personal Engagement

It seems primarily the artists and independent curators who are concerning themselves with postcolonial criticism from the perspectives of their own personal engagement. In the autumn of 2009 in collaboration with Asmara Pelupessy, Sara Blokland set up the Unfixedprojects platform, based on concerns within her own artistic practice in which she uses photography and cultural identity to zoom in on the multi-ethnic background of her Surinamese Dutch family. Unfixedprojects investigates the relationships between photography, postcolonial perspectives and contemporary culture. In 2010, the CBK (Centre for Fine Arts) in Dordrecht hosted an exhibition, symposium and artist residency. Questions concerning the role of the photographic image in the history of colonialism, migration and the diasporas as a complex visual exposé were investigated by Dutch and foreign artists and thinkers from the perspective of personal affiliations with colonial histories. Unfixed: Photography and Postcolonial Perspectives in Contemporary Art is a record of this project and will be released this fall by Jap Sam Books.

It is also by way of personal engagement that Wendelien van Oldenborgh, whose family has a background in the colonial history of Indonesia, concerns herself with this subject. She too is seeking a multiplicity of voices in order to break open a social issue that seems to be held captive by the continued reiteration of the same rhetoric. Once again, she is not doing this by replacing it with a new narrative, but by creating conditions in which to investigate possible positions in a complex reality. In her video works, her point of departure is historic texts being read aloud and commented on by people who have specific relationships to them. In this way, the texts are activated within the present context, in order to inform both the meaning of the historical moment and our current situation.

The curators’ collective Electric Palm Tree (EPT), initiated in 2008 by Binna Choi, director of Casco, and Kyongfa Che, a freelance curator in Tokyo, devoted their first EPT textbook to a collaboration with Wendelien van Oldenborgh. The book, A Well Respected Man, or Book of Echoes, which includes Van Oldenborgh’s scripts for No False Echoes (2008) and Instructions (2009) as well as texts from Indonesian colonial history and contemporary reactions to them, presents different forms of engaging with the current postcolonial condition seen from the perspective of Dutch Indonesian colonial history. The book reflects Van Oldenborgh’s practice of taking a new look at today through the lens of the past in order to reveal issues concealed in the current debate. With this book, which is being made available to educational institutes, the collaborators hope to show how to look at cultural politics in a new way.

As a platform for transnational exchange, EPT is itself an example of what a postcolonial practice might entail. In a new project with the Kunci Cultural Studies Center in Jogyakarta, a research project is being carried out on the word ulayat, a term for collectively owned resources, the commons, introduced to the Indonesian language by the Dutch during colonial rule. They look at how the meaning of this concept developed in both countries and how it can be applied in a new way in today’s society. Thus the notion of cultural translation, the way the meanings of objects, ideas and identities shift when they come into new contexts as a strategy for meaningful decolonization, lies at the foundation of EPT.

Another example is Duet for Cannibals, a four-part film programme organized in early 2010 at the Tropenmuseum by Inti Guerrero. Each evening was introduced by a colonial propaganda film from the museum’s collection, which was brought into dialogue with highly diverse film material. Guerrero created a complex visual and discursive construct in which sometimes literal but often more associative connections were created. Andy Warhol’s screen test with Susan Sontag was coupled with an archival film in which mirrors were held in front of colonized individuals after their heads had been measured. In both cases, it concerned the objectification of ‘the Other’, in which a moment of subjectivity simultaneously breaks through. Here, Guerrero was not looking at a specifically Dutch history, but wanted to bring the deeper experience of colonialism into the cultural discourse.

These practices, characterized by long-term investigations in which conditions for new positions and trans-cultural exchanges are created from the perspective of critical formulations, also need to be employed by museums in order to break open laden material histories. This means creating a dialogue in which the encounter with the other can take place beyond the simple reinforcing of cultural differences or the levelling of universalism.

Anke Bangma, appointed at the beginning of this year to the new position of curator of contemporary art at the Tropenmuseum, also hopes to work intensively with artists on projects that start from the formulation of issues rather than being based on the ethnicity of the artist, in order to set the museum and its colonial history in a critical spotlight and establish new connections between the past and the present. She is developing plans for an ‘artwork in residence’, in which works of art are guests of the museum for a period of time and travel through the collection in a visual investigation of the way meanings change in shifting contexts.

Bangma questions whether the colonial narrative should even remain a starting principle in the Tropenmuseum’s transformation into a museum of world culture (of which the West is to date not a part). Nonetheless, this is precisely the location where an investigation can take place that can make our postcolonial reality concrete. Many ethnology museums choose to work with contemporary artists as an instrument for institutional self-analysis, in order to use the subjective perspective to arrive at new insights. In this way, the collective narrative is being replaced by a micro-perspective of different voices and the original colonial museum becomes a kind of meta-text for continuing commentary on this complex global reality.

Regional

Art museums, which as a result of contemporary global developments are being forced into a similar self-examination, can also only do this from their own perspectives, their specific histories and collections, if they are not to fall prey to fragmentary and arbitrary policies. They can decide to become regional museums for Western art and position themselves as such, but if they wish to continue to play a relevant role in the new world order, a cross-cultural policy must be developed in which they can get a grasp on their own identity by way of a continuous process of self-reflection and exchange, in a kind of wilfully cannibalistic act.

This is more than just managing diversity, in which under the pressure of government and a politically correct morality the priority is simply some specific amount of ‘the Other’ in museum programming. It requires a critical reflection on one’s own exhibition practice and social role in a changing society. It is precisely in the context of today’s disturbing developments, in which both innovative culture and the multicultural society are shoved aside, that it is extremely important that art takes the lead in its own unique way. It is precisely in the development of alternative visions and practices that do not follow the market mechanism of rapid production and consumption that its real strength lies.

A constructive worldwide practice that recognizes a powerful political and cultural component as a new space in which differences, meanings and identities are set into continual motion, can only be brought about when we determine our own position from an interpretation of our past. If we do not wish to remain stagnant in a noncommittal discourse, then postcolonial criticism as adapted to our own histories has to take an important place in this social, geopolitical and cultural reorientation, one in which we are still waiting for an encounter with the phantoms of the colonial period.

Alice Smits is a curator and critic based in Amsterdam

Translated from the Dutch by Mari Shields

Published by Metropolis M, No5 oktober / november 2011

Colonial history / Global Art History / Museology /

Magazine

Article: Globalisation in Dutch Art Centres, by Vincent van Velsen

The distinction between western and non-western art is outdated

Het museum als instituut staat ter discussie (Dutch)