A screenshot from the workshop: Art for a Citizen Scene Doodle Lecture

A screenshot from the workshop: Art for a Citizen Scene Doodle Lecture Workshop Report: Doodle Lecture and Musical Hangout

by Julia Wilhelm

May 2021

Set to release in Spring, 2022, Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices wants to shed light on practices in specific communities where collaboration is common in daily life; where art is seen not only as a self-contained profession, but also as ways of living and being.

The publication process is accompanied by a series of online workshops/events in which we invite participants to gain insights into the dialogues, engage with the contributors, and co-develop design frameworks for the publication prior to its physical manifestation. Read Workshop Report: Hybrid eXperience for the first two workshops.

Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices is a collaboration of Framer Framed and the Willem de Kooning Academy (WdKA).

Workshop 3: Doodle Lecture

11 April, 11:00 – 13:00

In the beginning of the third workshop, artist and initiator of the project Reinaart Vanhoe (WdKA) explained that the publication aims to bring forward the value of ambiguous practices; that is, artistic or cultural practices that cannot be defined easily, that take many different shapes and demand various skills. Reinaart specified that clearly definable practices are often more valued in the art world, resulting in a lack of confidence of those who cannot outline their practice easily. The doodle lecture which Reinaart organised together with Betül Ellialtıoğlu (Framer Framed), intended to give participants insights into the practices of Rieneke de Vries and Zoénie Liwen Deng. By creating doodles and notes, participants were given agency in shaping the form of the publication.

We first walked into a small wooden house located in the West of the archipelago. Between sofas, games, and a kitchen, the participants could find a table with a huge chocolate cake surrounded by balloons, prepared for our first speaker Rieneke de Vries’s birthday. After singing birthday songs in different languages, Betül invited everyone to grab drawing materials or use the whiteboard embedded in the space to document their thoughts on Rieneke’s talk.

We Sell Reality

In her talk, Rieneke de Vries traced her path from the art academy to her present situation. She explained that after graduating from art school, she started working with homeless people, but saw it as something separate from her practice. Later, she brought them into her art practice by drawing and taking photographs of them. At the same time, she became more and more reflective of the social structures she was confronted with, but she felt caged in a state of reflection, separated from the things happening around her. This dissatisfaction led her to make more expressive artworks and take her first job as a social worker.

Due to the war in Syria and the overcrowded Asylum centers, the Dutch government started building tents to house arriving refugees. Rieneke soon began visiting and working in the camp. There, she met people from a multitude of backgrounds and built close friendship with several of them. The asylum procedures had very different outcomes for them, some were able to get a permit, while others encountered problems. For Rieneke, this resulted in a moment of reflection: What could she, as an artist, do in such a situation? That was when she first had the idea of a label called ‘We Sell Reality’, a label that would ‘sell’ the reality of European migration and the stories her refugee friends brought with them. To reach out and communicate their message to people outside the artworld, she thought about creating objects of everyday use with her undocumented friends. After Rieneke met Elke Uitentuis, they founded We Sell Reality together.

Treatment Plans and the Notion of Care

Next to her work for We Sell Reality, Rieneke took a job in a closed youth care institute as a social worker. The situation in the youth care institute was overwhelming: some kids were in difficult mental states and she was lacking the tools to deal with the situation. Rieneke became part of a treatment plan, while realising that her background as an artist made her look at the frameworks in which the institution operated in a more critical way.

Reflecting on her art practice and her activities as a social worker, she noticed that there are usually four layers in her work. The first layer consists of observation. In the second layer she connects with the people. In the third layer they enter a phase of co-creation. The fourth and final layer is to come up with a treatment plan that takes into consideration the psychological and social aspects of those involved and to come up with a solution. To her, the fourth layer is vital and something that often misses in artistic engagements. Rieneke admitted that being part of a treatment plan is a complex task that she sometimes succeeds in and sometimes fails.

After quitting her job at the youth care institute, Rieneke continued as a social worker in a community house in Rotterdam. As the funding for the project will end in September, she wasn’t sure if she should continue the social work path—which is entangled in institutional and political networks, or the art/applying for funding path—which is more detached from the ‘real world’. She ended her talk asking the participants for advice.

One participant said she appreciated Rieneke’s honesty, not pretending to be the perfect artist, but acknowledged her insecurities and struggles. Another participant noted that while the word ‘care’ seemed very popular in the current art world, to the extent that it risks becoming shallow, Rieneke really practiced ‘care’. There was no resolution for Rieneke’s dilemma, but many participants could relate to it. One participant mentioned that next to being a trained artist she also works as an art therapist assisting people who suffer from dementia, and always struggles with the question if the art or the therapy aspect has priority.

Non-Oppositional Criticality

Our next meeting point was a boat decorated with shells at the East of the archipelago. There, Zoénie Liwen Deng first introduced her recent PhD project[1] on non-oppositional criticality in Southern China, and later highlighted some aspects of her dialogue with artist, publisher, and urban practitioner Elaine W. Ho.

In her PhD project, Zoénie was interested in the notion of the Flowing and the Unstable as a political act, the main title of the thesis ‘Be Water, my friend’ stems from a quote by Bruce Lee:

“Empty your mind, be formless, shapeless — like water. Now you put water in a cup, it becomes the cup; You put water into a bottle it becomes the bottle; You put it in a teapot it becomes the teapot. Now water can flow or it can crash. Be water, my friend.”

Zoénie worked out four different forms of criticality practiced among artists and communities in southern China. The first one, Reconfigurative Criticality, refers to the reconfiguration of the public space and groups like Theatre 44. Connective Criticality is interested in forging connections between people and actively counter-forcing competitivity. For Uneasy Criticality, Zoénie uses the theatre project Home (2016) about migrant workers in Beijing as an example. Here, theatre is used to reflect on and deal with social issues while raising questions that make the audience uneasy. The goal of this form of criticality is to educate the public. The fourth one is Quotidien Criticality, which refers to engaging people on a daily basis.

Also-Dialogue[2]

Afterwards, Zoénie talked about her conversation with Elaine for the publication and how it influenced her own research and thinking.

Zoénie and Elaine started by exchanging texts to learn about each other’s practices and to have an entry point for the conversation. In the beginning of their dialogue, they shared some experiences with mansplaining and the fact that people who are better at articulating themselves are usually given more attention. Some of Elaine’s remarks led Zoénie to question her own research and how these power relations influence her work. Did she give enough attention to voices that are not that loud?

She went on to introduce some of Elaine’s projects, like HomeShop (2008 – 2013), a place where connecting, living, and eating together was central, or WaoBao, a swap event in which not only materials, but also stories were exchanged. In Elaine’s ongoing project Light Logistics, people volunteer to create otherwise infrastructures for publications to travel. Infrastructures that are not based on efficiency and money, and which often initiate new friendships and collaborations among the contributors.

Collectivity and Otherwise Futures

In the discussion following Zoénie’s presentation, one participant noted that the art system was in a legitimacy crisis. Other participants took up the question of how to navigate the ruined art world, for instance through creating bonds and effecting change on a small scale, or by hijacking the system and redistributing resources, like some initiatives already attempt. How can art as a radically imaginative way of doing and thinking help us to manifest a better future?

Some participants shared how they try to create change with small actions in daily life and referred to art and poetry as ways of connecting. Zoénie addressed the question of how to form a collective, a question that she had also asked Elaine in their dialogue. Nobody could give a concrete answer, but the participants figured out that collectives are always arising from a common goal or interest, and that in many cases collectivity is more a means than a goal. This recalls Elaine’s attempted answer in the publication:

“[…] there is no precision to the hows when there are so many different modes and intentions for organising. I was recently watching Agnes Chow’s YouTube channel, and in one episode a netizen asked her precisely, ‘How is a political party created?’ […]

I guess it’s not really something to create. It’s more when a group of people gather, there’s a really important question that you should be able to answer: what’s the difference between you versus the parties that already exist in Hong Kong right now? In other words, you should be possessing a very unique philosophy. Also this philosophy that you’re believing in should be a benefit to the future.

What is striking here is how the mandate for the new and unique, something of course so embedded within the arts, is also imbricated within the administration of politics and social change. We are all, always, looking for new ways to deal with the same old problems which have plagued societies since the dawn of humankind.”

Workshop 4: Musical Hangout

25 April, 11:00 – 13:00

During our fourth and final session of the series of the workshop, we went on a tour through the virtual archipelago in search for pineapples and chilis that contained videos contributed by Willy Chen Wei-lun— member of Trapped Citizen and Print & Carve Dept, and Wok The Rock— artist and musician, member of the collective Mes 56, who is also running the music label Yes/No Wave Music. Willy and Wok gave insights into their practices, talked about Guerilla gigs, music as a means of protest, the importance of collectivism, and their reactions to the pandemic.

Introduction to their Practices

A screenshot from the workshop Art for a Citizen Scene: Musical Hangout

We first walked to the North-East of the archipelago where Wok led us to a red chili that contained a recorded live performance of his band ‘The Spektakuler’. Wok introduced his collective Mes 56 and talked about how they figure problems out together just like a family. He added that a general attitude against institutional structures brought the members together. The next video he shared showed recordings of an after-party at Mes 56 where female DJs were at the center. He explained how in the music scene female DJs are often marginalised, so Mes 56 saw it as a necessity to create a stage for them.

Next on, Willy led us to a pineapple that contained a music video by the Taiwanese indie band No-nonsense Collective and introduced his collective Trapped Citizen. Trapped Citizen was founded in 2016 as a study group on Das Kapital by artists and musicians who met during the Sunflower Movement and protests against forced eviction. In another pineapple, participants could find a documentary about the punk collective Ponti, which Willy visited in Jakarta. Ponti shares many similarities with Trapped Citizen: both depart from punk ethos, favor horizontal organisation, and are located at the periphery of the cities. Willy also showed a short excerpt of a documentary about the Anarcho-punk band Crass that exemplifies the punk ethos that inspired Trapped Citizen.

Guerilla Gigs/Music-Art-Social

Together we walked to the second spot on the island further south, where Wok shared a video about his project Trash Squad commissioned by the Jakarta Biennale. Wok wanted to raise questions such as: What is capitalism? What is labour? He created a cleaning company composed of punks that would pick up trash around 7/11s in Jakarta, a common place for punks to hang out. For Wok, Trash Squad was also a way to redistribute the money he received from the Jakarta Biennale and a reaction to the bad image punks often have in public discourse. Some of the shop keepers were upset, while others were happy and gave them food and drinks. Wok also shared a video about his project Yoyo Art Bar, a social bar created in 2013 in Yokohama’s Koganecho neighbourhood. He conceived it as a temporary space for gathering, sharing and encounters.

Willy shared videos of Guerilla gigs that he started a decade ago as a reaction against the industrialised music scene. Those gigs were organised in public parks and other accessible spaces to challenge the institutional structures and the classical venues in the music scene. He then led us to a pineapple containing a recording of a performance that took place during the activist fest No Limit Tokyo Autonomous Zone organised by the Japanese group Amateur Riot. Trapped Citizen connected to their Japanese friends after the nuclear catastrophe in Fukoshima in 2011, which, with the following anti-nuclear demonstrations, marked a turning point for many social movements.

The Pandemic

At the next stop, Wok showed a video of a concert organised by Mes 56 on the virtual platform Rabu which is especially suitable for parties and online gigs. For Mes 56, it was crucial to find ways of spending time together and organising events despite the pandemic. The next chili contained a feature-film long documentary called Pandemic Improvisation co-created by Wok. The film shows how Indonesian artists respond to the pandemic and the difficulty to survive without being able to perform at concerts. In the film, several artists are displayed performing on the streets for passers-by.

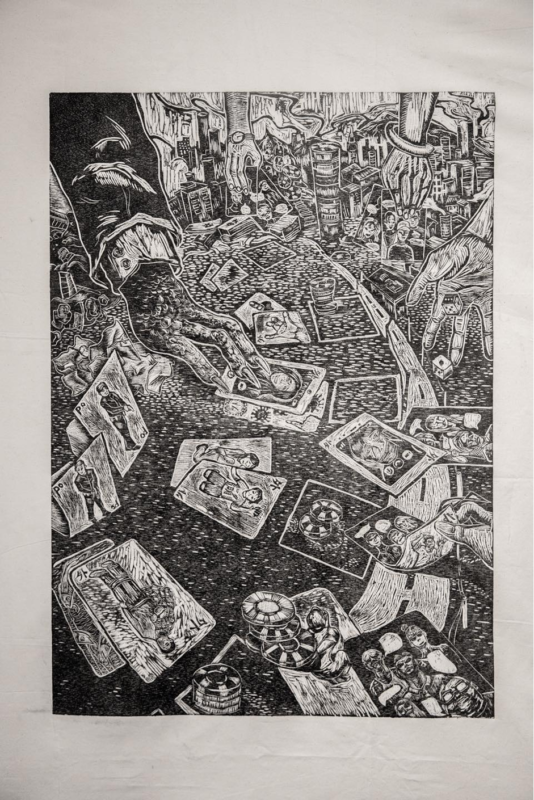

Willy’s next video showed a performance of the Wuhan based punk band SMZB in Taiwan organised by Trapped Citizens in 2018. After the outbreak of the pandemic, political-driven discourses of the ‘China-’, or ‘Wuhan-virus’ generated anxiety and xenophobia. To show solidarity with their friends, Trapped Citizen held a woodprint workshop and organised discussions featuring friends from Wuhan. Willy also shared a video of a set by DJ Lala, a student from Hongkong and member of the Taiwan International Student Movement. The movement fights for the rights of international students accused of bringing the virus to Taiwan. As a response to the discrimination, Willy’s collective Print & Carve Dept., a group of amateurs invested in making woodprints, created a woodcut showing a poker game as a metaphor of how non-citizens were discarded in moments of crisis.

A work made by Print & Carve Dept. in response to discrimination. Courtesy: Print & Carve Dept.

Print & Carve Dept. showing works at Taipei main station in 2020 to support migrant workers.

Print & Carve Dept also made works to support the occupation of the floor of Taipei main station in 2020 as a reaction to a ban issued by the government that prohibited gathering on the station floor, a popular space for migrant workers to hang out.

Collectivism

On our last stop, Wowo shared a music video he worked on with the experimental music group Senyawa. Wok and Senyawa share an interest in decentralisation and accessibility, Senyawa’s album was released by several independent labels who also publish remixes. Akin to that, Wok’s Label Yes/No Wave Music publishes tracks on their website which can be downloaded for free. For Wowo, sharing music is a way to support friends, and the label is an aspiration for ‘the democratization of the music industry’.

The last pineapple shared by Willy contained the movie Youth (2017) by Feng Xiaogang which follows a group of idealistic adolescents who are part of a military art troupe during the Cultural Revolution in China. Willy referenced this film because he thinks collectivism in Taiwan needs to be understood in relationship to the past; it is important to be aware of the historical and geopolitical context to understand the connotations the notion of collectivism implies to many Taiwanese citizens.

After the musical stroll in search for chilis and pineapples came to an end, Reinaart concluded that the aim of the project was to offer younger generations examples of otherwise ways of practicing art, and how it always needs to be understood as part of a complex ecosystem. Together we walked to a small island in the south-east to exchange some last thoughts on music, art, and activism. We ended the session with a collective experimental piano improvisation.

*We would like to thank all of the participants who joined the event and their creative contributions.

Art for (and with) a Citizen Scene: A Look at Art Primarily Active in the Context of Daily Practices is a collaboration of Framer Framed and the Willem de Kooning Academy.

Contributors of the publication: Elaine W. HO, Zoénie Liwen Deng, Rieneke de Vries, Brigitta Isabella, Mayumi Hirano, Sig Pecho, Wok the Rock, Willy Chen Wei-Lun, Bunga Siagian, Ismal Muntaha(JaF), Dicky Senda

[1] Zoénie’s thesis can be found online here.

[2] Zoénie and Elaine decided to call their dialogue also dialogue, after the initiator Reinaart’s project also space.

Citizenship / Community & Learning / Art and Activism / Politics and technology / Southeast Asia /

Agenda

Book Presentation: 'Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene' & 'Be Water, My Friend'

A joyous sharing on writing, reading and book making at documenta 15, Kassel

Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene 4: Musical Hangout

Online workshops for collaborative publication design

Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene 3: Doodle Lecture

Online workshops for collaborative publication design

Art for (and within) a Citizen Scene 1 & 2: Hybrid eXperience

Online workshops for collaborative publication design

Network

Elke Uitentuis

Visual artist and human rights activist

Zoénie Liwen Deng

Art writer and researcher

Chen Wei-lun

Community builder and artist

Wok The Rock

Artist and musician

Rieneke de Vries

Artist and Social and Creative Worker

Betül Ellialtıoğlu

Communication and PR