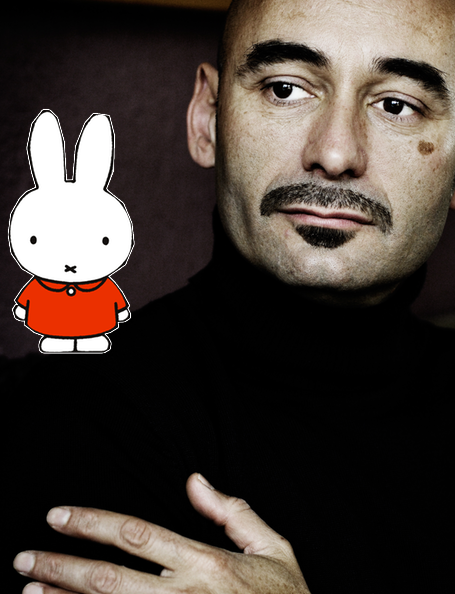

Photo: Marlise Steeman, Framer Framed

Photo: Marlise Steeman, Framer Framed Manifesto for an enfranchised museum

I

Traditional European class-ridden society is gradually crumbling. In its place we are witnessing the emergence of ‘emancipated citizenship’ along the lines of the American model, which offers anyone with sufficient intelligence, know-how, experience and opportunities the chance – in theory – to climb the social ladder. In this field of influence the position of the museums is also changing. Art is no longer an elitist affair. The choice of whether or not to visit a museum is no longer connected to a manifest respect of the arts, culture and cultural heritage. For a young generation the mystical experience of beauty has even in some instances become secondary. Instead, they want to exercise their own opinions. And here lies an opportunity for museums to help young people, and adults, to formulate and develop their personal position in a complex, globalized reality.

II

Museums have been ‘reservations’ from time immemorial; they manifest themselves as protected zones where rare species are protected from the outside world. Traditionally, these museum-reservations have staunch ties with the prevailing social elite. The emancipation process embarked upon in the twentieth century doesn’t just tinker with elitist thinking in general, but also with the synonymous masculine ego-centrism and dominant western ethnocentrism. This is a painful but necessary process that provokes all manner of political, social and cultural confrontations. For the enfranchised anti-elitist museum, the following applies: the only way it can lay claim to a meaningful position in contemporary culture is by fundamentally reassessing its own position in the social sphere of influence. Rather than acting as traditional bulwarks of white culture, museums sensitive to current trends should also pick up on other kinds of stimuli. Because in the museum-reservation of the future there is space and freedom for anyone with an inquisitive mind, be they rich or poor, male or female, black or white.

III

Over the last fifty years, the larger museums for modern art have increasingly come to resemble each other. Artistic choices are too often coloured by the individual ambitions of museum directors in pursuit of prestige and status. They seem to want to play a key role in the creation and consolidation of the canon, following in the footsteps of their illustrious predecessors – ‘art popes’ like Willem Sandberg, Edy de Wilde, Jean Leering, Wim Beeren and Rudi Fuchs. Because old-fashioned directors fail to appreciate the signals sent out by the younger generations, a monoculture is threatening to engulf Dutch museums for modern and contemporary art. A young, enfranchised museum does not confirm prevalent attitudes about art but, where necessary, questions them.

IV

Museums that neglect their own substantive power squander their identity. Bowing to quantitative successes is seductive: a popular programme can attract a large public relatively easily. In this line of thinking, quality and enrichment are of less importance. However, museum culture can only be rehabilitated by breaking the vicious circle of museum administrators and boards who anticipate and react to the judgement of politicians hungry for visitor numbers, who subordinate artistic policy to management and marketing. Museum ambassadors should leap to the barricades and convince private enterprise and local and national politics of the importance of a lively, qualitative exchange between contemporary culture and cultural heritage. As the party with overall responsibility, the government can play a key role in this: not just as ‘patron’ of the arts, but as a sensitive, nurturing partner able to create favourable conditions for new stimuli.

V

Embedding the contemporary museum in society requires an active, inspiring strategy where, as a kind of interface, the museum fosters an interaction between art, artists and the public. The bonds with new public groups are forged in the groups’ own environments, by working with schools, societies, vocational training institutes, local networks, universities and academies. This direct social involvement is the seed-bed of new support for the museum.

VI

The force field between the historicizing capacities of the museum and its role in the current cultural debate offers considerable opportunities. The ideal museum actualizes the past by incorporating historical layering and intensity in projects that have topical appeal. The museum can navigate a lively, stimulating course through history: it can reinterpret, learn and teach by highlighting developments and by demonstrating that countless histories can be written. To relate knowledge of historical heritage to present-day developments, curators need to become familiar with the museum collections actively involved in the museum presentation practice. But just as much scope is needed for the input of young artists and exhibition makers, for new initiatives and for the development of polemic exhibitions. VII The epicentre of contemporary art is no longer to be found in the museum but in the hybrid reality encompassing it. Contemporary visual art is a perpetual process of ebb and flow, along every possible route – images, situations, expressions, collaborative projects and territories. Documentas and biennales constitute the new hubs in which the circus of contemporary art temporarily descends in a fleeting configuration of makers and public. In this area of tension the museum plays second fiddle, but it can intensify the primacy of that evanescence by taking more time, by looking back, by asking questions and by creating contemplative moments.

VIII

A new generation of young artists is active, one that draws inspiration from the mediatized reality around them, and whose work is an immediate response to the visual culture they find there. They don’t retire to their studios; they don’t hide behind the purely aesthetic and are not primarily in pursuit of individual expression. They prefer not to make purely personal, autonomous objects that are divorced from reality, choosing rather to create new, hybrid connections that facilitate experience, emotion or critical reflection. Their artworks can take any form: painting, sculpture, film and video, photography, digital media, performance, fashion, design, architecture, drawing and installation, or combinations of various media. By directing their work at exploring and determining and revealing visual codes in a highly personal way through visual manipulation processes, they help us analyze the mediatized, capitalist visual culture and discover new meanings within it. The enfranchised museum responds to this by stimulating the analysis of visual culture and by forcing a tipping point in the traditional way we look at art.

IX

The enfranchised museum for modern and contemporary art is no longer an awe-inspiring institution. It is not a sacred white space, kingdom, cathedral, scientific institute and certainly not a school. It is a dynamic, hybrid place where the interaction between various artistic disciplines is a binding factor and where inspiring teamwork leads to adventurous combinations of collections, presentations and happenings. This type of museum acts as a window onto a complex and colourful world, inviting the public to assume an individual, reflective position. In a gradual, shocking, confrontational or playful process of looking, thinking and processing, standpoints can be exchanged and new opinions formed. Such a museum reveals a seismographic movement with deep roots in the past and inquisitive antennae opened to the world.

Edwin Jacobs, cultural intendant of Tilburg,

Meta Knol, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Centraal Museum, Utrecht,

Stijn Huijts, director of Museum Het Domein in Sittard.

NRC-Handelsblad, December 6, 2006

- NRC Handelsblad

Links

Museology /

Network

Meta Knol

Art historian