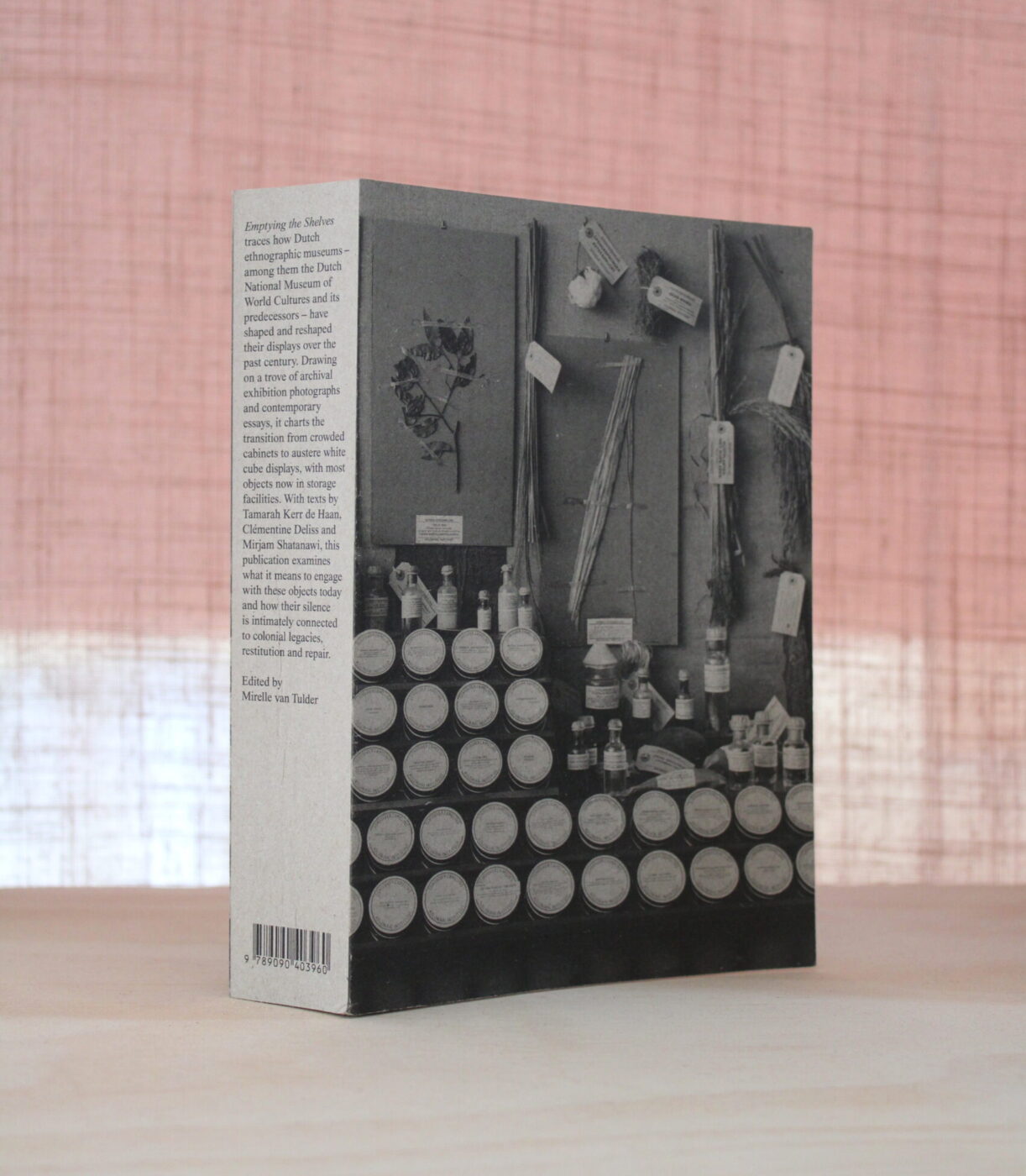

Emptying the Shelves (2025) by Mirelle van Tulder. Photo: Evie Evans / Framer Framed

Emptying the Shelves (2025) by Mirelle van Tulder. Photo: Evie Evans / Framer Framed Bookshop Selection: Emptying the Shelves

Framer Framed is pleased to announce the new publication Emptying the Shelves (2025) from Mirelle van Tulder, the Atelier KITLV-Framer Framed Artist in Residence. The publication is co-published by Roots to Fruits and Framer Framed. It traces how Dutch ethnographic museums – including the Dutch National Museum of World Cultures and its predecessors – have shaped and reshaped their displays over the past century. Drawing on a trove of archival exhibition photographs and contemporary essays by Mirelle van Tulder, Tamarah Kerr de Haan, Clémentine Deliss and Mirjam Shatanawi, it maps the shift from densely packed cabinets to minimalist white cubes, asking what these transformations reveal about colonial legacies, restitution and repair.

Buy it now through the link below!

At the heart of the publication lies a disquieting question: What happens to the countless objects collected, displayed and later hidden from view? Artist and designer Mirelle van Tulder approaches this history through what Rolando Vázquez calls a decolonial aesthesis: a visual and conceptual practice that challenges the modern/colonial gaze. By bringing together more than 200 archival photographs, many published for the first time, Van Tulder and her collaborators reveal how the museum’s display strategies evolved from crowded cabinets to minimalist white cubes yet remained bound to systems of representation that privilege the Western eye. The publication is also part of van Tulder’s artwork, featured in the group exhibition, Shapeshifters: On Wounds, Wonders and Transformations.

The book is available in the Framer Framed shop or online.

Author

Mirelle van Tulder

Contribution

Mirelle van Tulder,

Tamarah Kerr de Haan,

Clémentine Delius and

Mirjam Shatanawi

Graphic Design

Victoria Lum

Co-publishers

Roots to Fruits and

Framer Framed, Amsterdam.

Printer & Binder

Wilco B.V., Amersfoort

528 pages,

240 b/w illustrations,

13,5 x 19 cm

English

ISBN 978-90-90403-96-0

2025

Foreword

In her foreword, former Wereldmuseum curator Mirjam Shatanawi reflects on the discomfort of encountering ‘endless rows of shelves’ filled with displaced objects that testify to colonial accumulation and traces how ethnographic museums in Leiden, Amsterdam and Rotterdam built collections on racial hierarchies and colonial logics that persisted long after decolonisation. Shatanawi argues that even after decolonisation, the white cube’s neutral design merely masked the same entitlement that once underpinned the display of ‘other’ cultures.

Read the introduction here:

Having worked for eighteen years as a curator at the Wereldmuseum, I have never grown accustomed to the sight of endless rows of objects and artefacts in storage. Objects that arrived in the Netherlands through countless routes and across different periods. The work of Mirelle van Tulder exposes this accumulation: objects from around the world, housed in museums in the Netherlands, where they remain seemingly motionless, bearing witnesses to the collector’s greed and the curatorial belief that the world can be captured in pieces of wood, in fabric and other tangible realities. Some had been subject to outright looting and violent theft, while others were custom-made for Dutch clients and purchased at prices much higher than usual. Contrary to popular belief, many — if not the majority — of these objects were produced in recent years, thus decades after colonialism formally ended. I also learnt from my colleagues and friends in the countries of origin that some were dearly loved and their absence painfully felt, while others were not at all. So, why do these endless rows of shelves make me uncomfortable?

Discomfort and pain do not only arise from the single object, painful as its history may be, but from the sheer plenitude and the reasoning behind their accumulation. While researching the histories of these collections and reading numerous letters and notes from colonial collectors, I was struck by their casual tone and how obvious it was to them taking the objects to the Netherlands, as if it was obvious that they would be better off there. Within this casualness lurks the racialist notion that the Western world can better care for these objects. So, perhaps the crime is not in the taking of the singular object, but in the hundreds of thousands removed. Therefore, instead of focusing on the act of taking, I would like to draw attention to the absence of property. These are objects that are missed simply because they are no longer where they once were.

Colonial-era displays reflected the entitlement of European collectors, evident in shelves packed with objects. Most of the photos in this book come from the Wereldmuseum – an umbrella organisation uniting three museums founded in the nineteenth century that have divergent yet overlapping histories of colonialism. In Leiden, the ‘s Rijks Ethnographisch Museum, later known as Rijkmuseum voor Volkenkunde, focused on ethnological research and tried to establish the history of the development of humankind and the hierarchy of so-called ‘races’. One of the most influential directors, Lindor Serrurier, envisioned the museum as a scientific laboratory to study ‘primitive’ cultures. In 1895, Serrurier wrote that ‘[..] the museum will be, while retaining its scientific character, a school for everybody who wants to know how the wild, the barbarian and the half-civilised peoples have materialised their ways of thinking’. This changed from the mid-twentieth century, when the museum in Leiden was reshaped by the insights of modern anthropology and tried to show the diversity and uniqueness of so-called non-Western cultures.

The second museum in the Wereldmuseum agglomeration is the former Colonial Institute, later known as the Tropenmuseum, which was established – first in Haarlem, then in Amsterdam – for the promotion of colonial industry and production. The emphasis was on displaying and examining resources from the Dutch colonies in the Indonesian archipelago, Surinam, and the Caribbean islands: raw materials, natural produce, and applications of these resources in commodities and decorative art. The exhibition cases contained models of transport and housing in the Dutch East Indies, along with bamboo and cane, varieties of wood, agricultural produce, minerals, fibres, resins, fruit and foods. The focus was on products and it was not until 1926, when the museum moved to Amsterdam, that several rooms were added to showcase the cultures and arts of the inhabitants of the colonies. The third museum in Rotterdam, the Museum voor Land- en Volkenkunde, housed objects brought back by the city’s businessmen and shipping magnates, as well as missionaries and military officers.

What these museums had in common was the grouping of objects by ethnicity – Javanese near Javanese and Balinese near Balinese. The grouping was intended to enable scientists, whether anthropologists or geographers, to compare ethnic groups to determine their so-called level of advancement on the path to ‘civilisation’. Similarly, through this cultural labelling, visitors, anyone who was to set foot in the ‘Tropics’ – entrepreneurs, housewives, colonial administrators or military officers – could prepare for their journeys and familiarise themselves with the inhabitants of the colonies. Once objects entered the museum, the complexities of their original contexts were replaced by narratives that served museological purposes. Regardless of the individual aims of different museums, objects were reorganised according to the logic of museum ethnology, which was informed by the colonial project of hierarchising cultures. Despite varying institutional missions, whether scientific research at the Museum of Ethnology, entrepreneurial promotion at the Colonial Institute, or the training of missionaries and military personnel, all shared a common foundation: mapping and classifying the populations of the colonies was key.

Thus, museum displays and catalogues were structured along ethnic and regional lines, regardless of institutional focus. As a result, cultural representation within display cases was interdependent on constructed notions of ethnicity and race. Objects were recontextualised as educational exhibits, accompanied by labels offering generalised statements about the perceived characteristics of different populations. These practices must be understood within the broader aim of appropriating ‘other cultures’ and bringing them under the control of rational, ‘objective’ scientific knowledge. Throughout the history of the three museums, the essentialist framework underlying their approach remained firmly in place, persisting well beyond the end of colonial rule. The ethnographic museum organised itself through geographic division, with each region of the world its curator, exhibition space, and collection. In the museum displays these distinct cultures –‘Asia’, ‘Africa’, ‘Latin America’, ‘World of Islam’ – were made identifiable through easy-to-recognise cultural symbols and colour schemes.

Yet, curatorial discomfort with the way the museum operates is not a recent development. From the early years of Indonesian Independence in 1945, curators at the Tropenmuseum (now the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam) have been debating decolonisation. In 1948, this resulted in the removal of war trophies from the exhibitions, as a gesture to Indonesian visitors to avoid stirring up this painful history. In the 1950s, museum staff started to speak about being on equal footing – and how to translate this notion to exhibition displays. Diplomats from the newly independent countries were asked to send batches of objects to the museum, mostly industrial products that could represent the pride regained after Independence. Topics in the exhibitions changed, and the perceived ‘primitiveness’ was no longer the central focus. Instead, modernity was emphasised through themes such as healthcare, education and industrial progress. In the museum’s exhibition design, these notions of equality and progress were visualised by sterile glass cases, displaying isolated objects against a backdrop of plain colours. By mimicking the white cube of modern art museums (albeit often in more earthly colours), curators wanted to emphasise that objects from Africa, Asia, and Oceania should be perceived as artworks in their own right. The sleek design of the exhibitions exuded progress and optimism, while the isolation of objects aimed to encourage the neutral stance of the viewer.

Looking back, the museum staff’s optimism about shaking off the feathers of colonialism seems idle and the solutions they proposed merely cosmetic. Rarely did curators question their rights to the vast wealth of objects, nor did they reflect on their presence in Dutch museums—a presence that causes discomfort for many today. For too long, ethnographic museums have clung to the idle notion that cultures can be fully grasped when packaged into room-filling displays. However, these capsules that allowed white people to observe the world now feel obsolete. While the ethnographic museum is re-orienting itself – through thematic displays, decolonisation projects and a global outlook, the objects themselves are staring back at us.

Mirjam Shatanawi

Amsterdam, 2025

Originally published in Emptying the Shelves.

This text is licensed under a creative commons license BY-NC-ND 4.0 and republished courtesy of Mirjam Shatanawi and Mirelle van Tulder. Emptying the Shelves is co-published by Roots to Fruits and Framer Framed. This book is the result of the Atelier KITLV-Framer Framed Artist in Residency Program, and is made possible by the Creative Industries Fund NL.

Bookshop Selection / The living archive / Colonial history / Museology / New Museology /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Shapeshifters

A group exhibition examining how colonialism has shaped museums, archives and other institutions of knowledge

Network

Mirelle van Tulder

Artist, Designer and Researcher