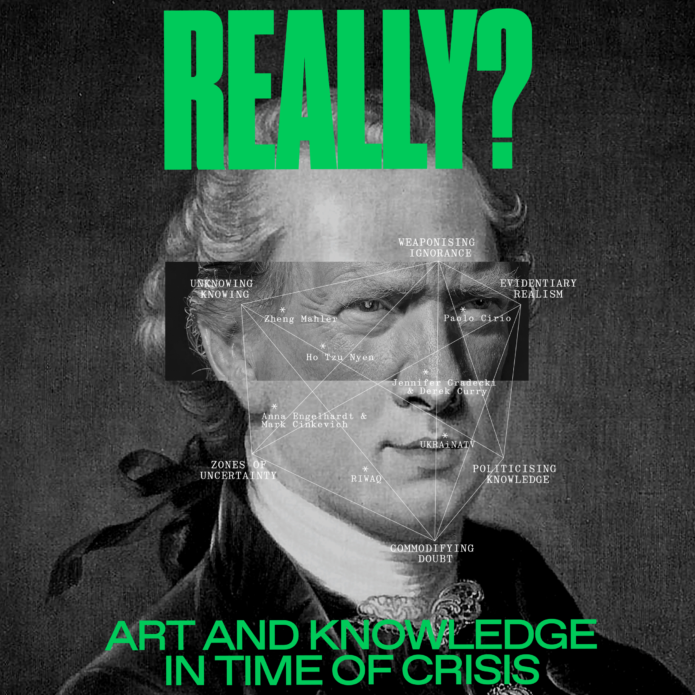

UKRAiNATV at the opening of the exhibition, Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis (2024) at Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

UKRAiNATV at the opening of the exhibition, Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis (2024) at Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Foto: © Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed Curatorial Statement: Art and the Battle for Truth

In their curatorial statement for the exhibition, Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis (2024), Mi You and David Garcia explore how artists address the erosion of trust in knowledge and the rise of disinformation through investigative and critical practices.

The exhibition Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis highlights a movement of artists who put the changing relationship between knowledge and politics at the centre of their practice. Typically, they combine a data-savvy ‘investigative aesthetic’ with a powerful ‘aesthetics of resistance’. They have come to prominence at a time when autocratic, reactionary populists are using sophisticated forms of misinformation to manufacture strategic doubt. This is more effective than traditional forms of state and corporate propaganda, as it suggests that the search for truth itself has become futile, successfully undermining the spaces of public reason where we might speak truth to power.

“The internet for all its benefits, has led to an epistemological crisis of unprecedented scale, facilitating the international rise of demagogues and reactionary populists.”

—Mark O’Connell, New Statesman (July 2019)

What is striking in this quotation is that Mark O’Connell has chosen to characterise our current predicament not as a political, cultural, economic or even an ecological crisis but as ‘epistemological’, a crisis of knowledge. Moreover, one of the aggravating symptoms of this condition is the way a new breed of malign state and corporate actors have bypassed traditional forms of propaganda. Instead, they are focusing on forms of misinformation that go beyond simple deception, operating instead through establishing ‘zones of uncertainty’ or ‘grey areas’. Well-established norms on subjects such as climate change, migration, poverty, race and sexual identity are not so much rebuffed through competing narratives but systematically called into question through tactics of obfuscation, irony, deniability, displacement and distraction. This is not simply about deception or the struggle between competing narratives, it is a war on knowledge itself.

AS IF: THE MEDIA ARTIST AS TRICKSTER

The stakes are high, as this is a condition we feel directly in our lives through the emergence of social divisions so deep that we do not simply disagree; we no longer share the same reality. It is a condition that has been building for decades. Indeed, it was already the subject for us back in 2017 in an earlier exhibition at Framer Framed titled As If: The Media Artist as Trickster, which featured artworks that infiltrate the media landscape with tricks, ruses, subterfuge and other tactics whereby the weak turn the tables on the strong in an asymmetric battle for the social mind. The show’s title emphasised the approach of these tactical tricksters who, rather than simply demanding change, acted As If change had already taken place.

We began using the slogan ‘Fiction as Method’ to push these tactics forward. However, Paolo Cirio, one of the artists in the show, objected, stating that he did not see his practice in those terms. In contrast, his approach was founded on a form of data-driven realism, offering new ways of speaking truth to power. The years that have passed since As If have only intensified the need for art that stakes a claim in a new politics of the real. It was deep within the complexities of this debate and its nuances that were the starting point for the exhibition, Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis.

INVESTIGATIVE AESTHETICS

In 2016, curator Tatiana Bazzichelli took an important step towards emphasising an empirical approach to artistic research by focusing on the aesthetics of ‘whistleblowing’, or as she called it, “art as evidence”. Bazzichelli’s event, CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE, was significant in exploring the investigative impact of grassroots communities and citizens to expose injustice, corruption and power asymmetries.

This realist approach was further articulated by Paolo Cirio, who introduced the term ‘Evidential Realism’. Typically, this formation refers to artists who combine data gathering, data analysis and digital imaging to illuminate complex social systems for broadly progressive social purposes. Cirio has described how “the truth-seeking artworks […] explore the notion of evidence and its modes of representation”. It is noteworthy that this is possibly the first fully fledged research-led contemporary art movement with explicitly empirical methodologies.

Scientific realism applied in art for progressive ends is not new. Antecedents of the evidential movement were already in place in 19th-century naturalism, which self-consciously modelled itself on empirical methods. One of the clearest examples can be found in Émile Zola’s literary theory and practice developed in texts such as Le Roman expérimental, which deploys an idealised notion of the scientific method to art in order to bring about social progress. Artists like Courbet and novelists like Dreiser and Zola were not bystanders, they were socially engaged. 19th-century naturalism was a political project as much as an investigative or aesthetic one. This exhibition and its accompanying debates seek to answer the question, who are their counterparts today?

KNOWING AND UNKNOWING

Although Evidential Realism represents a meaningful response to the rise of populist demagogues, we are keenly aware that this movement carries risks of its own. The new realists do not persuade through evidence and analysis alone but also through extensive visualisation of data analytics; this work has a tendency to project an aura of the irrefutable. It is a visual language with a powerful aesthetic appeal to modernist sensibilities. But, to what end? Haven’t we learned to be sceptical about anything that resembles a universal and uncomplicated scientific empiricism? The counterargument is that despite the risks, these new realists offer a combative response to the widespread accusation that contemporary art is part of a wider cultural relativism that has lost belief in the truth. This exhibition could be seen as a space for unpacking and contesting these claims and counterclaims.

We cannot speak of knowledge in this context outside of how data is classified and organised. To this day, descriptions of the natural world operate within an 18th-century Linnaean taxonomy with its distinction between genus and species. Though still dominant, botanist Adam Rutherford has pointed out that it is a pre-Darwinian system based on biological sciences that go back to Aristotle’s fixed and hierarchical scala naturae, or ‘great chain of being’. However, the most politically consequential and malign aspect of the Linnaean scheme of classification arrives with the publication of the twelfth edition of Systema Naturae in which he divides homo-sapiens into four distinct subgroups or ‘races’, attributing to each behavioural characteristics and value judgements which in any era are clearly racist. This could be seen as the birthplace of the pernicious cult of scientific racism, which has been used to justify the worst horrors of subsequent centuries, including colonialism, mass murder, the Shoah and chattel slavery.

Our own world, entangled as it is in algorithmic computation, is also no stranger to taxonomic hierarchies whose workings remain alarmingly secretive and opaque. And equally prone to entrenching sinister hierarchies of power and knowledge that intensify silos and feedback loops, whilst contributing to a general collapse of trust in the institutions that are supposed to ‘know’.

ARTISTIC RESEARCH BEYOND THE ACADEMY AND THE ART WORLD

Though subject to pressures, key institutions remain intact and underpin many developments in art and research through the combined resourcing and legitimising power of the art world and the academy. Art historian Claire Bishop wrote, “Although research-based art is a global phenomenon, it is inseparable from the rise of doctoral programs for artists in the West, specifically in Europe, in the early ’90s”.

Perhaps the most developed example in this domain of a positive role for the academy is Forensic Architecture. This important group is configured as a research centre at Goldsmith’s University in London. In this institutional framework, there is support for a critical mass of interdisciplinary researchers, including journalists, architects, 3D modellers, animators, coders and lawyers who are capable of managing multiple projects. This extraordinary combination of disciplines and experimental methods routinely achieves outcomes that are not only respected in legal and journalistic contexts, but are also featured in major art venues around the world. However, it is an example that is by no means universal or even typical. In his influential book Knowledge Beside Itself, art historian Tom Holert points to a strong and problematic correlation between the increasing importance of knowledge production in contemporary art and the simultaneous rise of the global knowledge economy. Holert argues that this transformation has made art an influential agent in shaping contemporary knowledge.

In her essay, Aesthetics of Resistance? Artistic Research as Discipline and Conflict, artist Hito Steyerl echoes Holert’s concerns, emphasising the risks of academic institutionalisation. She highlights the fact that practitioners are likely to find themselves “complicit with new modes of production within cognitive capitalism”. However, Steyerl also argues that these risks are just one part of a much larger story and should be weighed against a parallel history of artistic research that could be viewed from the perspective of global movements of struggle and emancipation that can be seen across most of the 20th century. This under examined long view of artistic research is usefully characterised by Steyerl as an aesthetics of resistance.

The artists/researchers in the exhibition, Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis have each found distinctive ways of embodying an aesthetics of resistance. Furthermore, they have done so in the context of multi-layered debates about what it means to know and not know within the fragmentation and relativisation of knowledge in a multipolar world.

The central challenge to us all remains how to identify and mitigate the consequences of life in the midst of a crisis in knowledge and a crisis in politics, which one and the same thing. The exhibition aims to expand a space of practical reasoning, which recognises that knowledge is not a zero-sum game. As much as we can and should validate facts in the public domain, as we also learn to identify the places where we no longer know.

- Aesthetics of Resistance? Artistic Research as Discipline and Conflict

- Evidentiary Realism

- CITIZENS OF EVIDENCE

Links

Curatorial Text / Colonial history / Art and Activism / Politics and technology /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis

Exhibition about the commodification of knowledge and ignorance, curated by Mi You and David Garcia

Exhibition: As If - The Media Artist as Trickster

On politically inspired media art that uses deception in all its forms. Curated by Annet Dekker and David Garcia i.c.w. Ian Alan Paul

Agenda

STREAM ART DAY with UKRAiNATV

All-day event focused on streaming practices, hybrid and tactical media, stream art and expanded TV

24 Hours Oost: Exhibition tours 'Really? Art and Knowledge in Time of Crisis'

Guided tours as part of 24 Hours Oost's programme celebrating Amsterdam's 750th anniversary

Opening: Really? Art & Knowledge in Time of Crisis

Opening of the exhibition about the commodification of knowledge and ignorance, curated by Mi You and David Garcia

Network

Mi You

Academic and curator