Lezing: Remco Raben - The modern art & literature of Indonesia

Lezing: Remco Raben - The modern art & literature of Indonesia Report: What is modern Indonesian art?

Throughout March and April 2017, Framer Framed hosts a series of lectures on the influence and relationship of imperialism on literature and visual arts in the former Dutch colonies. These lectures are organised together with the chair of Dutch-Caribbean Literature of the University of Amsterdam (UvA) – Prof. Dr. Michiel van Kempen.

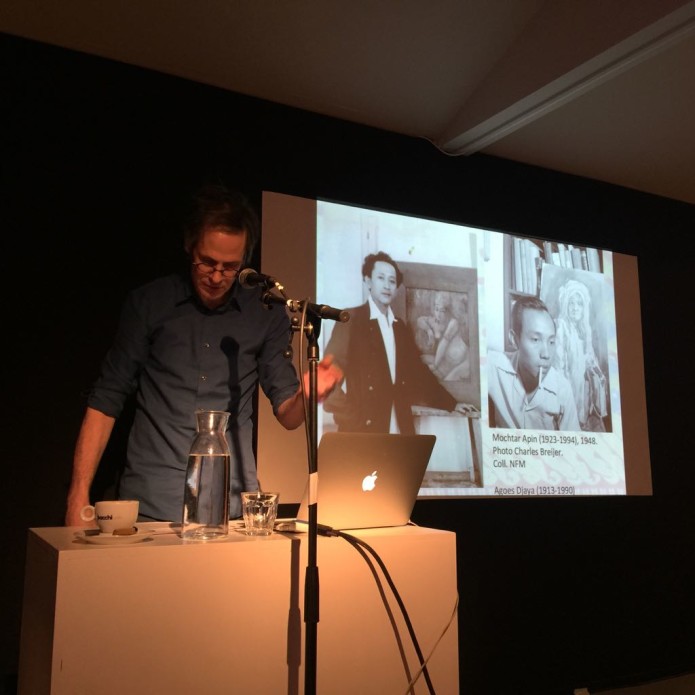

The second of these open lectures took place on the 17th March 2017 and was given by Prof. Dr. Remco Raben, who teaches Colonial and Postcolonial Cultural History and Literature at the University of Amsterdam. As the speaker explained at the beginning of his lecture, his presentation, titled Modern? Indonesian? Art? Indonesian painters between nativism and internationalism, 1940s – 1950s, stemmed from his interest in Indonesian art – which emerged whilst he was working with museum director and curator Meta Knol –, and from his knowledge on the concept of decolonisation.

Remco Raben started his lecture by explaining how Indonesian society changed throughout the mid-20th century. This period, which saw Indonesia’s rise to independence from the Netherlands (and its complicated political aftermath), was marked by a heavy sense of change and renewal. In terms of culture, artists wanted to create their own “independent artistic language” (in the speaker’s words) – both individually and nationally. Throughout this formulation, the term “modern” was widely embraced: it signified a rupture with the past, and a willingness to prove Indonesia’s role in the new world that was being shaped. As Remco Raben explained, however, the word “modernity” is an uncertain concept for art historians and researchers; as it can refer to both a specific period and an eagerness to break with past times. Moreover, it links to the West in unclear ways – as being “modern” often implied being Western. Therefore, the question that the speaker posed at the beginning of his lecture would also serve as a guiding thread for the rest of the talk: does modernity imply Westernization; and if so, how does it reflect on the creation of the Indonesian nation?

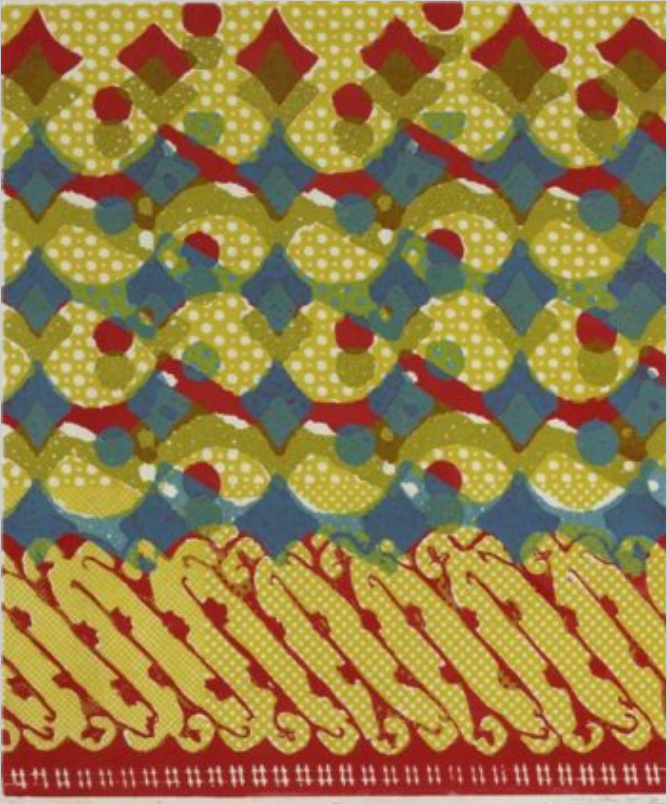

Raben first questioned the myth forged around the idea that during the 40s and 50s Indonesia saw the rise of modern(ized), national(istic) Indonesian art. By exploring the case of well-known painter Sindoedarsono Soedjojono, the speaker wondered if all the artistic production of those decades can indeed be interpreted as a nationalistic pursuit – which is what art historians seem to have read into that period until now. Soedjojono – who established the painters’ community Persatoean Ahli Gmbar Indonesia (Persagi) in 1938 with the aim of creating a platform to discuss the state, future, and techniques of Indonesian art – published a manifesto in 1939 calling for a new Indonesian painting style that grew closer to Indonesian people: a style that would move away from colonial landscapes and strive to depict the “real” lives of the population, thus embracing “realism as a political (nationalist) act” (to quote the speaker). This, in Remco Raben’s words, pointed towards a conflation of artistic renewal and political nationalism. Although later many Indonesian painters travelled to Yokyakarta during the Indonesian National Revolution (1945-1949) to depict the struggle, and realism established itself as part of the nationalist painters’ agenda; it is important to keep in mind that the artistic production of that time was much more varied – as many other artists left Indonesia and travelled the world, and others developed styles that were closer to Western art.

According to the speaker, the artistic and cultural complexity of this period can be interpreted through the lens of decolonisation; as these artists wanted to distance themselves from the omnipresent colonial powers and create their own Indonesian style. This, however, developed into an ambiguity; as many of these same artists looked to the West for inspiration. With this, a new debate that lasted until the 1960s was established: could artists and other cultural producers develop a new and modern Indonesian culture that would break with past forms, without drawing inspiration from Western art – or was the West a stimulating and desirable source of cultural knowledge?

A well-known work that fed into this debate was Armijn Pane’s novel Belenggu, published in 1940. Not only was the novel an adopted Western form: the subject of the plot – a love triangle imbued in a modernized lifestyle – borrowed much from Western literature too, but without any Western characters in it. Although this was an attempt to update Indonesian literature, it is nonetheless conflictual that it was done using a classically Western form; and that the story was framed as “an opposition between East and West” (quoting the speaker). A second example of this debate was the Polemik Keboedajaan discussion; where writer and editor Takdir Alisjahbana argued for the inclusivity of Western models in new forms of cultural production (with the aim of nurturing a new Indonesian style), whilst other authors and artists called on – what Remco Raben calls – the indigenous sources of inspiration of Indonesian culture. This debate splashed onto painting too, as artists continued to explore how to create a sense of modernity in Indonesia.

Whilst the previously mentioned Soedjojono seemed to search for raw, indigenous Indonesianness in his realist visual art, other artists explored different means of renewal. To delve into this, Remco Raben focused on two different painters who portray two very different styles: Agoes Djava and Mochtar Apin. As the speaker mentioned throughout his presentation of these two artists; they shared similar concerns – and for the sake of the lecture, he focused on their ambiguities.

Agoes Djava – who came from a privileged family and attended colonial schools, and later established the aforementioned Persagi group with Soedjojono – did not aim his artistic attention at portraits of everyday life; but at renditions of Indonesian folklore and traditions (for instance, by portraying the Hindu culture of Java). Whilst he seemed to go further and further into the past to search for a true Indonesian culture, he moved to Amsterdam – as a cultural ambassador – and exhibited his art, throughout 1947 to 1949. As for his position on Indonesian art: Remco Raben stressed how Agoes Djava’s opinion on the topic was never coherent nor definite, as he acknowledged that Western culture was attractive for Indonesians – but, in Raben’s words, Djava also deplored the general lack of interest in Indigenous cultural heritage. Moreover, it seems the painter already saw his position was problematic, as he believed Western culture was in crisis – and Eastern culture could be helpful in solving this impasse.

The second artist Remco Raben focused on was Mochtar Apin. Apin, who was also taught by Dutch drawing teachers, was part (and unofficial leader) of the Gelanggang Seniman Muda artistic group (established in 1946). To quote the speaker’s words, the Gelanggang group believed in the “republican ideal of a free and unitary Indonesia” – and were specifically inspired by Western artists when creating their art. Interestingly, the group published a manifesto in which they saw themselves as “the true heirs of world culture” (as the opening line of the manifesto reads) – thus stressing the internationalist essence of the organization, without forgetting the Indonesian culture and society. As for Apin himself; he proved himself as a gifted and resourceful artist by venturing into different painting styles (such as cubism and fauvism) throughout his European travels, even experimenting with abstract art in the 1970s for a short period of time, before turning to figurative painting once more.  Towards the end of his lecture, Remco Raben went back to questioning the term “modernity”, stressing the fact that it is a concept only used by artists and art historians. To speak of “modernity” or “the new” is, in the speaker’s words, to obscure “the differences and eclecticism” of the different artists and their paintings. Moreover, the focus on the heavy nationalist aspect of “modern” Indonesian painting of those decades has eventually shadowed the many contrasts and discrepancies of these artists. Throughout his analysis Raben did not negate the existence of Indonesian nationalist art; but he called on the importance to understand the concept of “national art” as an emblem or claim, more than a style or development. A compelling case was made for the painters’ individuality, as they seemed to seek to develop their own personal style whilst embracing the assertion that they were pursuing the creation of a new, modern national identity.

Towards the end of his lecture, Remco Raben went back to questioning the term “modernity”, stressing the fact that it is a concept only used by artists and art historians. To speak of “modernity” or “the new” is, in the speaker’s words, to obscure “the differences and eclecticism” of the different artists and their paintings. Moreover, the focus on the heavy nationalist aspect of “modern” Indonesian painting of those decades has eventually shadowed the many contrasts and discrepancies of these artists. Throughout his analysis Raben did not negate the existence of Indonesian nationalist art; but he called on the importance to understand the concept of “national art” as an emblem or claim, more than a style or development. A compelling case was made for the painters’ individuality, as they seemed to seek to develop their own personal style whilst embracing the assertion that they were pursuing the creation of a new, modern national identity.

Additionally, to speak of decolonisation in those times is to give way to an ambiguity; as a Western term (modernity) was used to gain distance from the West. This ambiguity also points towards the need artists had to relate to their own society and culture in a period that saw Indonesia rise as an independent and global nation. As Remco Raben interestingly interpreted, when in search for a style that is neither purely indigenous nor fully universal, nationalism served as the notion that connected the artist to the rest of his society. Along these lines, it is also paramount to point out that this dilemma was not only essential to Indonesian culture, as similar ambiguities also materialized in other non-Western countries.

As a response to these uncertain and ambiguous terms, Remco Raben closed his presentation by suggesting the use of the word “emancipation” instead of modernity – as it describes the aforementioned dilemmas of Indonesian art in the 1940s and 1950s in a more informed manner. The speaker then briefly answered some questions from the audience and discussed several topics; including the term “modernism”, the apparent lack of female artists during the reviewed period, and how privileged these artists were to travel and live abroad. Once the audience’s questions were over, Michiel van Kempen took the floor to close the lecture. With this, the event at Framer Framed ended; concluding an evening during which many of us undoubtedly learned a lot – and not only about Indonesian art, but also about heritage, cultural struggle, and the immense complexities of the recent history of the 20th century.

Iona Sharp Casas

Indonesia / Colonial history /

Agenda

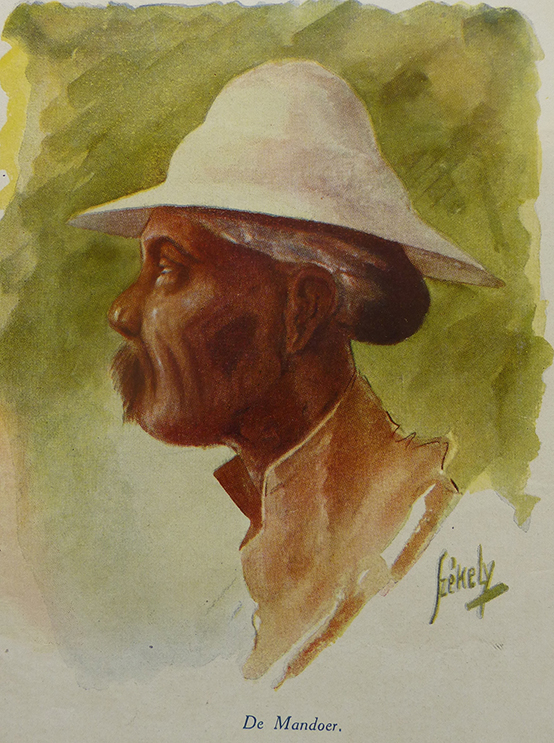

Lecture: Gábor Pusztai on the work of László Székely

Lecture on the work by artist László Székely, who lived and worked in the former Dutch Indies.

Lecture: Sara Blokland - Srefidensi and the reproduction of a family history

Lecture by Sara Blokland, about her art and the the project SrefidensiFoto, photo archives and the role of memory and identity in her work.

Network

Remco Raben

Historian

Magazine

Report: Modern Indonesian painters in revolution and nation building

Report: Exploring oral history as autobiography in the Curaçaoan context

Report: Lecture by Gábor Pusztai on the work of László Székely