Lara Baladi - The Friday of Victory after Hosni Mubarak’s fall Tahrir Square Cairo Egypt. Part of 'Vox Populi"

Lara Baladi - The Friday of Victory after Hosni Mubarak’s fall Tahrir Square Cairo Egypt. Part of 'Vox Populi" Verslag: Public Debate 'Vox Populi and The Syrian Archive'

Tying into the opening of the exhibition As If: The Media Artist as Trickster, on the 20th of January 2017, Eric Kluitenberg organised – together with curator David Garcia and Framer Framed – a number of public events. The events were also part of a bigger research trajectory called Tactical Media Connections, exploring the legacies of Tactical Media and its links with the present, which was started by the organizers in 2014.

The first of these, named Vox Populi and the Syrian Archive: documenting revolution and conflict in the digital age, took place in the Eye Film Museum on the 21st of January. This public debate sought to connect practices of digital documentation and online archiving with their relationship to activism and art; particularly focusing on (or starting from) the legacies of the previously-mentioned phenomenon known as Tactical Media.

In order to take up these topics the organizers invited five guests: Egyptian / Lebanese artist Lara Baladi (creator of the Vox Populi project), activists Hadi Al Khatib and Jeff Deutch (from The Syrian Archive), professor Charles Jeurgens, and American artist Robert M. Ochshorn. The event was moderated by the organizer, Eric Kluitenberg, together with curator Annet Dekker.

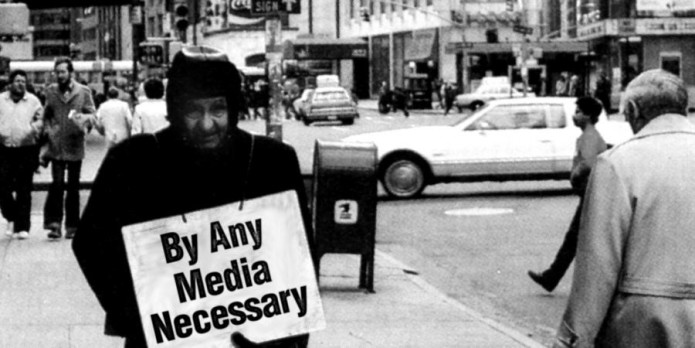

Before introducing the first speaker of the evening, Eric Kluitenberg highlighted the connections between the practice of (digital) archiving and the Tactical Media phenomenon; as well as the legacies of the latter, which are greatly present in the exhibition As If: The Media Artist as Trickster. Whilst presenting the Tactical Media Files website (which will soon be redesigned) he explained how Tactical Media sought to be a conversion of people making their own media instead of relying on the given channels: by taking the camera into their own hands and turning it onto a particular event as it unfolded, the subject holding the camera created her or his own media piece.

Although these practices are now common – as Eric aptly put it, we now all carry a camera in our pockets –, this was not the case in the 1990s: these types of media interventions were marginal and numbered in their time, deployed mainly by artists and activists. However, in the early 2000s, they slowly shifted into the mainstream – thus opening a new media landscape and changing the previous dynamics entirely. Hence the emergence of the Tactical Media Files initiative: despite it gradually becoming a main-stream topic – and the proponents of the Tactical Media term decided to stop organizing its eminent festival (Next 5 Minutes) – they continued to receive questions on the phenomenon. This prompted them, in 2008, to put together the website as a documentation resource – a sort of incomplete, un-authoritative archive – that connects Tactical Media and its practices to their past, present, and future.

In thinking of Tactical Media as a phenomenon through which the subject creates her or his own mediatic account of an event; and placing it in relation to recent socio-political movements and currents; there are several events that stand out as bearing possible Tactical Media-like tendencies. As Eric Kluitenberg explains, this includes the enormous wave of demonstrations and occupations that took place in 2011-2012, widely known as the movements of the squares. These movements relied heavily on their media presence (for instance, on Twitter), as their participants flooded the web with material on each of the demonstrations – in Eric’s words, they were heavily “drenched in media”. By questioning the role artists have in these events, as well as the fate of all the mediatic material created during the occupations, the moderator very fittingly introduced the first presenter of the event: transdisciplinary artist Lara Baladi, who created the digital archive named Vox Populi, Archiving a Revolution in the Digital Age.

Vox Populi was an initiative born in Cairo during the 2011 uprisings, as a product of the intrigue and curiosity towards the new ways of image-making – and image-disseminating – the revolution inspired. The project consists of a digital archive of all the material collected during the Tahrir Square uprising; as well as of a creation of essays, sculptures, and other initiatives that relate back to data and information collected. After explaining her own reasons for taking part in this revolution, the artist introduced examples of the material collected in her archive: photos, videos, political satire and graffiti, to name a few. Her focus, in her own words, was “the material that is produced by the random citizen”; particularly because of the creative wave that took place after Mubarak’s regime (which had previously been very strict in terms of artistic creation).

Lara Baladi then explained how her way of working as an artist involves collecting big amounts of material created through popular language, and then reflecting on it through artistic production – which is a process that allowed her to “digest” all that had happened. Followingly, the artist presented some of the works she had created as a response to all the material she managed to archive. These include the immersive surround sound and video installation Don’t Touch Me Tomatoes & Chachacha (2013) (which focuses on the experiences of harassment women suffered throughout the 2011 Egyptian revolution, and women activists and artists’ voices in the world at large); and an event she organised at Harvard in 2014, together with MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), in which she immersed the participants in the archive she had collected on the uprising, thus representing it instead of attempting to explain it – whilst protests were happening outside, at Harvard itself.

At this point of the presentation, Lara Baladi mentioned that she now wanted to focus on her present project, that emerged from using her archive not as an alone, singular tool, but as one of many: one that involves other data and archive initiatives that were born in the Tahrir Square revolution. A first outcome of this is a data visualization project of an index of archives on Tahrir she created together with Robert M. Ochshorn: a map of the online spaces in which people are either still speaking about the Tahrir uprisings, or webpages that have collected material. Furthermore, Lara Baladi’s next stage is to work with the individual pieces of data to create a “horizontal” narrative: in her own words, whilst the internet provides a vertical experience – as we open windows and click links, we seem to go down a whole –, she wants to lay out this information in a horizontal manner; through using timelines, information gathered from other archives, and other sources.

Towards the end of her talk, Baladi highlighted her role as an artist in creating the archive, and touched on the complications of being involved in such a project (particularly with the current situation there is an Egypt). She then presented her previously-mentioned ongoing project with Robert Ochshorn, which involves displaying archives in a visual (and animated) way. An example of this is their visual rendition of the editing of several Wikipedia pages that took place during the first months of the uprisings, thus allowing the viewer to have a type of “bird’s eye” – and horizontal – view of the number of edits that were made to several Wikipedia pages (such as, for instance, the Muslim’s Brotherhood page) during that intense period.

The artist ended her presentation by pointing out the next steps in her project: to complete her database as much as possible, and connect the material to other archives that have other types of data (such as, for instance, a legal archive of the American University in Cairo). Referencing Baladi’s words, this will allow for a narrative construction that connects the people’s voice (Vox Populi) with information that is much more structured (such as legal or historical data); as well as admitting a broader overview of how the present connects to the past, and to other events that are not necessarily framed as part of the Egyptian uprisings of 2011.

After answering some brief questions from the audience, Lara Baladi engaged in a small and interesting discussion on the linearity and functionality of her project – in which she again appropriately stressed her role as a visual artist (not a historian or archivist). After this, Eric Kluitenberg took the stage to call on a video that is archived on the Tactical Media Files website – a video by activist in exile Rami Nakhle, filmed at the start of the Syrian conflict in 2011 – to introduce the next speakers of the afternoon: Hadi Al Khatib and Jeff Deutch, who are part of The Syrian Archive initiative.

The Syrian Archive is a user-generated data initiative launched in 2014. In Hadi Al Khatib’s words, it is “a platform that collects, verifies, analyses and investigates visual documentation of human rights violations” in Syria. The goal of the project, to quote their presentation, is to create an evidence-based tool that can later be used for accountability purposes by human right activists, organisations, and lawyers. As the speakers explained throughout their presentation, they have already worked – and are still collaborating – with several groups, people and centres (including Amnesty International, the United Nations, Human Rights Watch, and many others); who are helping them develop all the necessary stages of the project.

To start their presentation, Hadi Al Khatib explained how in recent years there has been a shift in how conflicts are being reported: whilst before reporting was more dependent on official channels, it is now very much user-generated. Interestingly, the speaker pointed out how, since the start of the Syrian conflict, there have been more hours of online footage generated than hours of conflict. However, there are several problems that come with this; particularly related to the erasure or loss of content (due to its physical destruction, or erasure from the net by the platforms where it is posted), the fact that the evidence is unverified (as the amount of data that exists is huge), and it is unsearchable (for instance, when a video is uploaded, its metadata becomes stripped or fragmented).

Continuing their talk, Jeff Deutch explained how they address these problems; for instance, by creating an automated back-up system, designing a methodology for verification, and applying a metadata scheme. The speaker also indicated some concerns or criticism their project has come across; such as the impossibility of making it a completely apolitical initiative – since despite trying to be as neutral as possible, they must (for instance) make choices on how to classify their data –, or the fact that they cannot transparently represent the Syrian conflict – as they depend on visual data only. Despite these issues, The Syrian Archive successfully manage to continue working through their concerns, and construct their remarkable project.

To do so, they use a methodology that involves a structured number of steps; such as establishing a list of sources, having a list of people helping with verification, employing a useful metadata scheme, and storing the information securely. By meticulously verifying the material they receive (which involves collaborating with on-foot contacts in Syria, using Google maps, and other strategies), The Syrian Archive is often able to recognise, for example, not only the date and geolocation of an attack – but also the type of weapon employed. Additionally, this means that the information can later be used in reports and investigations by human right groups and similar organisations. Hadi Al Khatib ended the presentation by introducing several of their case studies; explaining how the visual evidence collected (by individuals recording the attacks on Aleppo, published Russia Today videos, and other sources) allowed them to research and demonstrate, together with human rights groups, in what manner chemical weapons and cluster munitions are still being used in Syria – despite the authorities are claiming otherwise.

Once the presentation of The Syrian Archive was over, the moderators permitted a few questions. After a fruitful Q&A that touched on several topics – including the material’s legal context and its process of classification, the integrity of the data, and the process of negotiation between protecting their sources and publishing the material –, and after taking a short break, Annet Dekker introduced the following speaker of the afternoon: professor Charles Jeurgens.

Charles Jeurgens presented a response to the previous two projects, bridging his classic or traditional archival perspective with the digital archives introduced earlier. He first interestingly pointed out how, from his point of view, the archive is not so interested in the difference between digital material and non-digital material; but in the essence of the archived material itself: questions on what the archived documents are, or who recorded them, must be asked when confronted with both digital and non-digital records. Jeurgens also explained how The Syrian Archive can be interpreted as a more traditional archive – as it has a well-defined purpose –; and although its future legal function is still not clear, he emphasized the importance of collecting and contextualising the information they gather (even if it is to have, as he says, a more reconciliatory role in the future – as ‘memory boxes’ had after Pinochet’s dictatorship).

As for Lara Baladi’s project, Jeurgens stressed how it combines a personal way of creating documents with – in his own words – “the messy world of the internet”; as well as how these dynamics of communication are represented in the archive. After, the speaker emphasized the power of the archive: rather than focus on what the archive is, he focused on the relationship between the document and its creator. Remembering the Syrian Archive’s presentation, Jeurgens underlined how collecting and classifying data never involves apolitical decisions, as it generates several ethical questions. Followingly, he compellingly called on the necessity of being critical towards the ‘standardization’ of the archive; as it always means leaving data and material out – and these choices will affect the collection.

Charles Jeurgens ended his response by speaking of the sustainability of digital archives, as well as of the activist aspects they involve. In his own words, “the digital media requires action”: archivists need to be active for the project to be created. Additionally, he questioned what kind of institutions one needs to rely on to make sure digital archives will last into the future. Although we might think that nowadays we are less dependent on institutions because of the internet, the speaker asked how much of that is true; as not institutionalizing a project such as the ones presented during the event might also come with the danger of framing them as temporal initiatives – thus becoming easily forgotten.

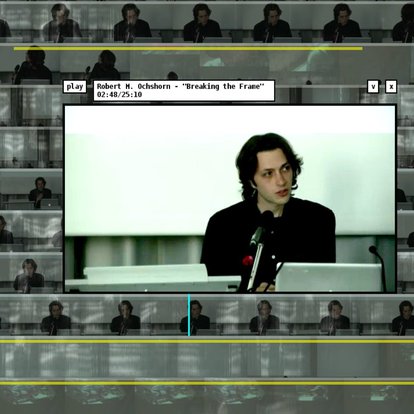

After Charles Jeurgens’ presentation Eric Kluitenberg introduced the last speaker of the afternoon: artist Robert M. Ochshorn. As the moderator explained, Ochshorn creates vibrant and vivid interfaces of media collections (such as the one presented in the As If exhibition at Framer Framed, which is a visualization of the Tactical Media Files website); focusing not only on their technical aspect but also turning them into fascinating artworks.

Robert Ochshorn started his presentation quoting Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium, to give sense to a certain narrative underlying his work. The text, on the concept of lightness, starts by emphasizing Calvino’s working method as one focused on “the subtraction of weight” (quoting the author directly: “above all I have tried to remove weight from the structure of stories and from language”) – and ends speaking about computer science[1]. Ochshorn then presented his work on the Tactical Media Files archive – Tactical Recollections No. 1 – as being, in a way, relatable to Calvino’s words on lightness: it is an animated, visual narration of a digital archive, in which every video represents a document of the archive and every line is 1:00 minute long. By hovering over a video and pressing on it with the computer mouse the video is played in an interactive way, but the reproduction of the video can also be abandoned as soon as the mouse is unclicked – thus allowing for a similar type of mediacy (in Ochshorn’s words) to the one that is presented in Calvino’s text.

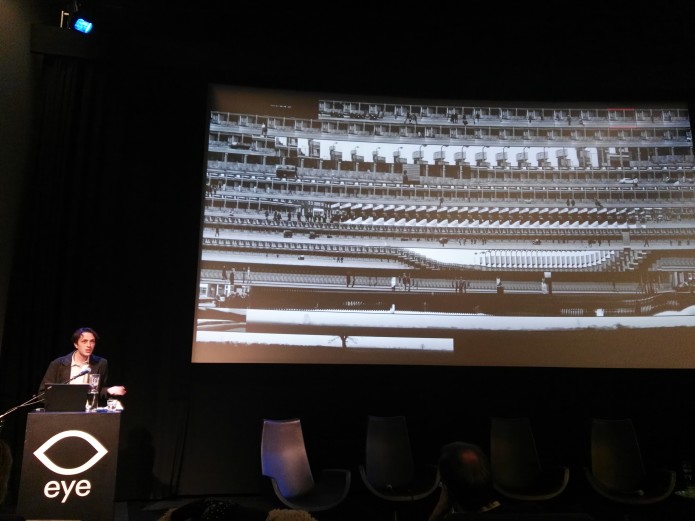

Followingly the artist introduced some of his other works; such as Montage Interdit, which is a history of the Middle East told through the work of cinema director Jean Luc Godard. This visual narrative is organised conceptually and through several layers, thus inviting the spectator into an archive that reminds us – as the speaker puts it – of a cinematic editing room.

Additionally, throughout his presentation Ochshorn spoke of some of his works as maps, playing with video animation and time-scales as if wanting to offer agency back to the viewer (so she or he can choose whatever point of entry is preferred, and make sense of it in her or his own way) – as well as discussing the “materiality” of the video in itself. An example of this is his rendition of John Smith’s film The Girl Chewing Gum (1976) – called Chewing Time (2013) –, through which the viewer can watch the entire film at once. He also called on his efforts to have the viewer create metadata (what he calls, “metadata as a creative act”) by, for example, not adding a ‘full screen’ button to the videos played in Tactical Recollections No. 1 and Montage Interdit: this way, one is forced to make sense of the video in relation to the rest of the archive.

Interestingly, many of the works he introduced that afternoon seemed to have similar underlying tensions and purposes: to create visual and animated renditions of data and information that would otherwise never be presented in such a manner; transforming archives, collections, video, or other classic forms into playful, mosaic-like, representations that can be practical, interactive, and visually-fascinating interfaces at the same time.

After introducing several other projects Robert Ochshorn ended his talk by presenting some his last works, very much related to the question of the interface and how much of it is controlled by the hardware / software, but focusing on the materiality of an object instead of on the screen. To go back to Calvino and his aspirations towards weightlessness, Ochshorn and his collaborator created prototypes that, quoting his words, mediate the physical relationship between human touch and digital software; exploring how physical objects respond to software as well as to tactility and gravity (thus perhaps moving in a certain way or another, or becoming weightless, or heavy, through a given perceptual connection). The artist then ended his presentation by stressing the importance of experimenting with different ways of creating meaning and making connections, particularly in the archive: ways that are less authoritarian, and more connected to the viewers and the public.

Once the talk ended Eric Kluitenberg and Annet Dekker asked the rest of the speakers of the afternoon to join the stage, so a debate could take place. This debate touched on several aspects, including a discussion on openness and participation in the archive; and Eric’s reflections on the topic of re-interpretation. Through the latter, the moderator re-phrased David Garcia’s question to Lara Baladi on the nature of Vox Populi: is it an archive or a monument, or a re-interpretation of one of the two? To this, Lara Baladi appropriately answered that she preferred to think of her work as a tribute: humbler than a monument, it can represent the dynamics of communication that took place in the square. Additionally, Lara Baladi emphasized the importance of initiatives such as The Syrian Archive; stating that these are real political situations with tragic consequences in which the practice of archiving becomes an act of resistance. It is not about attempting to reproduce history nor constructing something that will be useful in the next decades; but about preserving the resistance tools that are left, as well as resisting and remembering reality as it is – in the present.

The Syrian Archive added to this by pointing out that they do not know if what they are doing will be legally admissible in the future. However, by documenting their methods the process can be re-made; and other tools for gathering evidence can be created. The debate then shifted to other questions; focusing on Robert Ochshorn’s artistic trajectory, the inevitable degradation of digital platforms, and the need of protecting these for the future – which, as Lara Baladi said, might not be the goal of all artworks. After discussing the (sometimes, necessary) opacity of certain parts of the archive, each one of the panellists answered final – and very well posed – questions by Steve Kurtz (who would speak the day after at the Society of Post-Control conference). Here, Robert Ochshorn spoke about his work’s resonance with the avant-garde; Lara Baladi recalled the dialogical nature of her collection (and her authority in it); Charles Jeurgens pointed out the differences between archiving and collecting; and Hadi Al Khatib and Jeff Deutch amusingly but meaningfully explained how someone recognised cluster munitions on a video published by Russia Today. After these final remarks the moderators closed the event, and the conversation moved – informally – to the bar.

Even though discussions on archives and archival practices are sometimes accompanied by age-old questions; the freshness, relevance and urgency of the topics debated in this event were nothing short of inspiring. Learning about initiatives such as The Syrian Archive and Vox Populi is a reminder of the importance of the concept of the archive; and of how it needs to continue evolving and embracing new forms without shying away from the digital and media necessities of the 21st century. Additionally, and although we may never find answers to some of the questions raised during the event, we might want to take Robert Ochshorn’s advice and strive to experiment with new meaning-making connections on an (inter) disciplinary level. This would allow, perhaps, for informed collaborations between artists, theorists, and activists, who can assess and create feedback loops that benefit the formation of much needed projects, such as the ones discussed throughout this event.

Iona Sharp Casas

[1] Calvino, Italo. “Lightness”, from Six Memos for the Next Millennium (1988).

Het levende archief / Midden-Oosten / Nieuwe media / Politiek en technologie /

Exposities

Expositie: As If - The Media Artist as Trickster

Over politieke mediakunst waarin verschillende vormen van misleiding centraal staan, samengesteld door Annet Dekker en David Garcia ism Ian Alan Paul

Agenda

Symposium: Vox Populi and The Syrian Archive

Symposium over de relatie tussen digitale archivering en activisme.

Netwerk

Robert M Ochshorn

Kunstenaar, programmeur, muzikant

Eric Kluitenberg

Auteur en programmamaker

David Garcia

Kunstenaar, academicus