Hadassah Emmerich

Hadassah Emmerich Interview: Kunstenaar Hadassah Emmerich

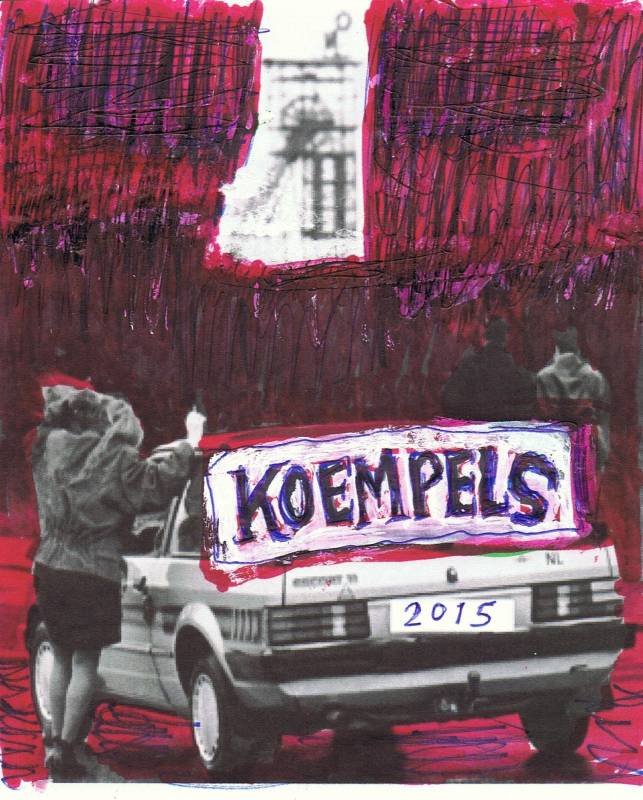

Hadassah Emmerich is a Dutch artist based in Brussels (Belgium). The artist has held recent solo exhibitions in Switzerland, the Netherlands, the United States, in Indonesia and Germany. As we are doing this interview, Hadassah is in Amsterdam for the opening of the exhibition Koempels, in which she presents three of her works. The exhibition is hosted by Framer Framed, and curated by Lene ter Haar in cooperation with Rik Meijers. It presents the work of six other artists – Joan van Barneveld, Fons Haagmans, Sidi El Karchi, Keetje Mans, Rik Meijers and Bas de Wit.

We start off by talking about this exhibition…

It is very interesting for me to exhibit with this group of artists because we all know each other from Limburg and we all respect each others work. The curator, Lene, chose to make a reference to the group Amsterdamse Limburgers who in the past tried to escape the limited view and possibilities which Limburg offered at that time. I believe that the connection between this social-historical aspect and painting is a very interesting layer in this exhibition.

Hadassah was born in Heerlen, in Limburg. This province located in the South of the Netherlands was for long known for its large peat and coal mining industry.

Did the mining history and culture have an impact on you and your family?

Yes, quite directly, since my grandfather from my mother’s side was a miner. When I was born he was already retired and that was the same year when the last mine in Limburg closed down. I can still remember a picture that my dad took when I was around two years old. In the background you can see the ‘Lange Lies’ chimney. I think the picture was taken on the day when it was going to be blown up. I think that was why he took a photograph of it. When I was younger I didn’t realize it, but when I think about it today it is disturbing to think that the physical memory of the buildings and of the mining activity is gone, as if it never happened…

And did this mining history influence your work?

Not directly, but I have come to understand that something in my upbringing strongly influenced my work. It relates to a certain mentality which came to me through my mother, who was raised in a miners’ family. It was a very polite and hard-working mentality, but it brought with it certain boundaries around what could be described as the working class. It produced in me a driving force to break out from it, to go somewhere else and to create things that are larger than life. And I believe that this relation between a sense of repression and a feeling of having to break out from it is directly visible in my work.

At the moment and for a few days while in Amsterdam, Hadassah is creating a new artwork on one of the large walls of the Tolhuistuin. It will remain there after the exhibition is over in December 2015 and for an indefinite period of time. I had the chance to see Hadassah at work and was amazed at the technique she was using.

Could you tell me more about this technique and how it relates to the works exhibited in Koempels?

The direct relation between these works is the technique I am using, called over-printing. I started using it last year and since then it has been developing to become what it is now. This technique is very important for me and it relates to that idea of repression caused by a fixed mentality and type of thinking. This feeling is in a way represented by the templates and their repetitive patterns. Beneath this is the under-layer, which I deliberately paint in a very free way, without censoring myself. This technique helped me resolve a lot of issues, and has helped redefine myself as a painter. The technique can also be applied directly on the wall, and allows me to be more adaptable to the limitations of time when I am creating a site-specific work.

Do you remember what got you into art in the first place?

I lived with my mother who had to work a lot. In a way I think that the fact that I was quite often alone as a child led me to start drawing. My mum put me in piano and dancing lessons, but I ended up dropping these other activities, while the painting and drawing continued.

You went on to study Arts at University, first in Maastricht (the Netherlands), and later in Antwerp (Belgium). What led you to Belgium?

I was looking for a way to extend my studies and I felt that after the years I had spent in Maastricht I also wanted to open up my horizons. I applied to different universities and it was in Antwerp where I was accepted. In hindsight I am quite happy how this turned out as I got to know a lot of great and interesting people at the HISK (Hoger Instituut voor Schone Kunsten).

And later you studied in London for two years…

Yes, and this experience was very important for me. At that time I was 29, I was already exhibiting and my themes were becoming more and more explicit. But I still felt the need to frame the conceptual thinking around my work, which I felt had been lacking in my education and I found it hard to find those references by myself. For me it had always been important not only to make but also think about art, especially since the topic of ’the exotic’ is so complex.

With all the changes in your way of creating and thinking about your art, can you identify a common element which has been present throughout the years?

Yes, the ideas of survival and the exotic have always been very important. It can be seen in the fertility symbols I use, and in the idea of abundance. On the other hand, there is the relation between oppression and liberation, which has become more and more defined. When I look back I can see that all these issues have always been present and important in my work, as a driving force and part of how I view existential matters. They are present in my work where I try to keep a balance between the intellect and the emotional world. That is why the over-printing technique works so well for me, since I can free myself but at the same time think about which references I want to use, such as Gauguin and primitivist woodcuts.

How do you think other people characterize your art?

I got known through the big, colorful murals, as well as for the idea of abundance and the exotic.

Hadassah Emmerich – Blue Bayou (2015), displayed for the first time in exhibition Koempels at Framer Framed

Where do you derive your inspiration from?

I have always had a liking for environments, which started mainly after a visit to Southern Italy. Here I came across the famous Catholic murals and their visual abundance impressed me a lot. Western society is based on the idea of economy of means, and in a way these murals completely break through this idea. Even though they were created in a different time than our own, these murals reveal a type of devotion which really touched me, and I have since then been interested in understanding it.

Amongst all your work, can you think of one specific work or collection which had a special impact on you?

The most recent one is The Inverted Table, which was specifically made for an exhibition at Stedelijk Museum Schiedam. It combined many layers which I had been trying to bring together. It refers to the idea of the worldly, the looking out into the world, searching for references, through an inclusive type of approach. The painted work included a vitrine where I displayed personal items which I had collected over the past 10 years. I had been carrying these items with me in boxes, from Antwerp back to Limburg and then to London. Finally, last year I decided to open them up and I found all these strange objects, such as a folded bag from the Frida Kahlo exhibition at the Tate Modern, and which had some paint on it. With these objects I tried to be very critical and I decided to display them in an associative way, not only according to personal connections but also in a formal way, by creating a visual poetry.

When you are creating new works do you think about how it will be received by the audience?

Definitely. Due to the nature of my working practice, which includes a site-specific part, people come to have a look and have a chat. And in a way this gives oxygen to my work since I get an immediate response and reaction from people, just from them asking me what I am doing. Through different experiences I have noticed that my work has managed to touch people through different social layers. For example, the cleaners in a museum who witness the progression of my work and who often comment on the changes they saw during it’s development. I am very happy with this aspect of my work. For me it has always been a strange idea that there should be a separation between the person on the street who doesn’t care about art and the art in institutions which is in a sort of cage known only to the insiders. Although I know the importance of the inner circle and the economy of the art world, and I am aware of the fact that art is not for everybody, I support the idea an ‘inclusive’ art practice that is able to communicate on different levels.

On a concluding note, besides the work you are producing at the moment at the Tolhuistuin in Amsterdam, is there anything else you are working on now?

Yes, back in the studio (in Brussels) I will start preparations for an XXL painting of 9 x 3 metres for Art Rotterdam Intersections 2016. And I look forward to going back to that work and to focus on developing the over-printing technique in paintings, which vary from small to very large.

Interview by Sofia Lovegrove Pereira

Further reading:

About the mines

Mining in the Netherlands

Demijnen.nl

Extractivisme /

Exposities

Expositie: Koempels

Een expositie over de sporen van het Limburgse mijnbouwverleden in de hedendaagse kunst, samengesteld door Lene ter Haar

Agenda

Maand van de Geschiedenis: de NDSM-werf en de Limburgse mijnregio

Transities in postindustriële gebieden.

Netwerk