Taring Padi, Solidarity in Public Space - by Kerstin Winking

One day this spring, I joined the Wayang Kardus Workshop organized by the artist collective Taring Padi at Framer Framed art space in Amsterdam. Aside from making shadow puppets (wayang) with cardboard (kardus), the workshop entailed hanging out for hours with people from the neighborhood and the arts community while sharing conversation, food, and drinks, and enjoying live music. Taring Padi’s home base is in Yogyakarta but members of the collective have been organizing a series of Wayang Kardus Workshops abroad, ahead of their participation at documenta fifteen in Kassel. Few participants at this happy gathering in Amsterdam would have initially guessed that the event is rooted in over two decades of radical political activism through art. Background knowledge was not required to participate in the workshop because Taring Padi’s mission is to educate people about pacifist activism at all levels, with inclusion as a fundamental principle.

A carnival with banners by Taring Padi remembering four years of the Lapindo Mud Tragedy in Siring Barat, Porong, Sidoarjo, East Java (2010). Courtesy of ArtAsiaPacific and the artists.

To give attendees some context, at the start of the workshop, historian Alexander Supartono introduced the practice of Taring Padi, who have utilized wayang kardus as a means of public resistance against state oppression since the group’s formation in the mid-1990s, during the final years of Suharto’s New Order regime (1968–98) in Indonesia. The cardboard puppets are crucial to their mass actions, because they serve to, in Taring Padi’s words: “voice protest and aspiration; ‘double up’ the number of participants; create lively ambience; protect from the heat of the sun,” and “protect from the physical aggression of the securities personnel.” This list of the wayang kardus’s functions testifies to the collective’s lived experience of non-violent protest in volatile situations, such as Indonesia’s Reformasi in 1998, the point at which Suharto’s military dictatorship came to an end and the post-Suharto era began.

Before joining the workshop, I had read the article Of pigs, puppets and protest (2000) about Taring Padi, written by one of its early members, the scholar Heidi Arbuckle. She notes that the collective’s protest wayang builds on the popularity of wayang theater performances in Java. However, in contrast to traditional wayang in which a puppeteer (dalang) voices all the puppets, in Taring Padi’s performances, each puppet has its own voice. This polyphony mirrors the group’s attachment to the principle of collectivity, which is important to them not only during protests but also organizationally. As Supartono told me, Taring Padi has existed for more than 20 years without legal representation or a single director figure. Instead, they work with activity-based coordinators. Decisions are always made collectively even if that process sometimes causes controversy within the group. Trust is the glue that keeps them together regardless.

At one point during the workshop, I sat down with Hestu Setu Legi, another early member of Taring Padi, who is temporarily living in Berlin. We talked about the early years of the collective. “In the beginning,” he said, “we all came together in the student movement, from different directions, but with the same feelings about the future and a dream to create something different with this movement in Indonesia. We felt we needed to build a culture and art organization.” Between 20 to 30 early members gathered in the abandoned building of the Akademi Seni Rupa Indonesia (ASRI, Arts Academy of Indonesia), where they began squatting a few years before the fall of Suharto in 1998. Most of them were students at ASRI’s successor, the Institut Seni Indonesia (Arts Institute of Indonesia), which had been relocated to a different neighborhood. Supartono reminded me that when Taring Padi got together, Indonesia was still a highly policed state, where official gatherings were subject to state control. In this context, the social practice of nongkrong had subversive potential.

Wayang Kardus Workshop at Framer Framed (2022). Photo: Ju-An Hsieh

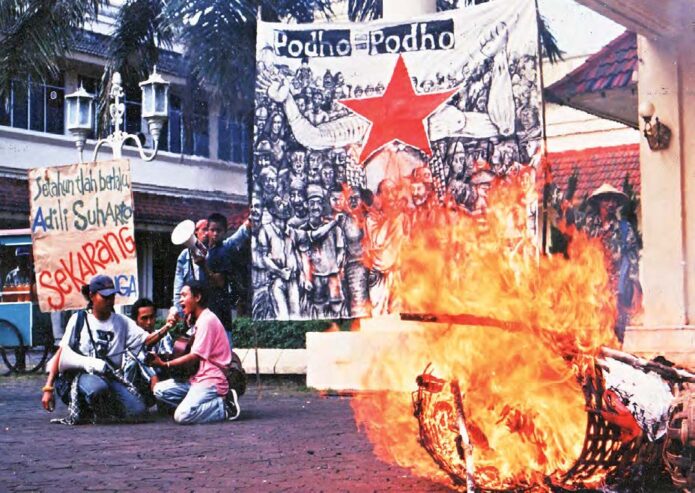

In a minimalist translation, the Indonesian word nongkrong means hanging or chilling out. It refers to a way of spending quality time together, drinking, smoking, and talking without any specific agenda. As an exchange of thoughts, nongkrong is an everyday activity for which people in Indonesia take time. Nongkrong can, but need not, lead to further action. In Taring Padi’s case, it unleashed more than 20 years of grassroots engagement in the context of post-Suharto Indonesia and, occasionally, in international contexts. Initially, they directed their work against Suharto’s military regime and militarism in general, but soon they were also protesting environmental pollution, racism, and discrimination; and advocating for gender equality, LGBTQ+ and women’s rights, and the right to speak critically about religious intolerance or societal traumas such as the 1965 Indonesian genocide, when the Indonesian army and Western proxies killed suspected communists and ethnic minorities. All of these subjects are sensitive in Indonesia, even today, and the Taring Padi artists have experienced violence and aggression from fundamentalists as a result of broaching these topics.

The banner from 2005 with the slogan Bongkar Tuntas Kejahatan Suharto 1965 (Completely Uncover Suharto’s Crimes of 1965) is a good example of Taring Padi’s collectively made protest paintings. In meticulous detail, it caricaturizes Suharto as a giant trampling over the masses while holding the Supersemar (Order of Eleventh March) agreement in his hand. In place of the giant general’s genitals, his open trousers disclose an image of Sukarno under duress, with one of Suharto’s soldiers holding a gun to his head, signing over control for the investigation of the 1965 violence and, in effect, handing over the state apparatus, to Suharto.

The group’s radical collectivism is also reflected in the original name its members chose in 1998: Lembaga Budaya Kerakyatan Taring Padi (the Institute of People Oriented Culture of Taring Padi). Since then, younger generations have joined (and left) the collective. These younger people were critical of the collective’s original name and argued to change it to the less-formal-sounding Kolektif Taring Padi (the Community of Taring Padi). The different generations of Taring Padi have in common their active engagement with urban and rural communities, whether self-initiated or upon invitation. Core members like Hestu Setu Legi keep things ticking.

View of Taring Padi’s Podho podho (1999), acrylic on canvas, 300 × 300 cm, at a 1999 protest calling for Suharto to answer for his crimes. Courtesy of ArtAsiaPacific and the artists.

An example of the collective’s activities was relayed to me by Fitri DK, an artist, sociologist, and second-generation Taring Padi member. In their 2010–11 engagement with the village of Siring Barat in Porong, a district in East Java, Taring Padi protested alongside residents against the extraction of the area’s natural gas by the Lapindo Brantas company. The drilling had disastrous consequences for villagers and the environment. In 2006, a blowout in a drilling well helped create a man-made ‘volcano’ that caused highly pressurized mud to rupture the surface, creating massive mudslides that buried people’s houses and polluted the soil and nearby rivers with heavy metals. When Lapindo Brantas continued to deny responsibility, Taring Padi took action with the villagers. I saw a banner produced for this protest in Solidaritas tanpa Batas/Solidarity without Boundaries, Taring Padi’s 2021 exhibition at Marketview Arts in York, Pennsylvania. The painted banner depicts the villagers standing like a wall in front of a landscape ravaged by a mudslide. Above them, the slogan reads Adili Lapindo, Tuntaskan Gantirugi Korban Lumpur (Bring Lapindo to Justice, Complete Compensation for Mud Victims). Taring Padi’s photograph of the protest in Siring Barat shows the villagers and the collective carrying the same banner.

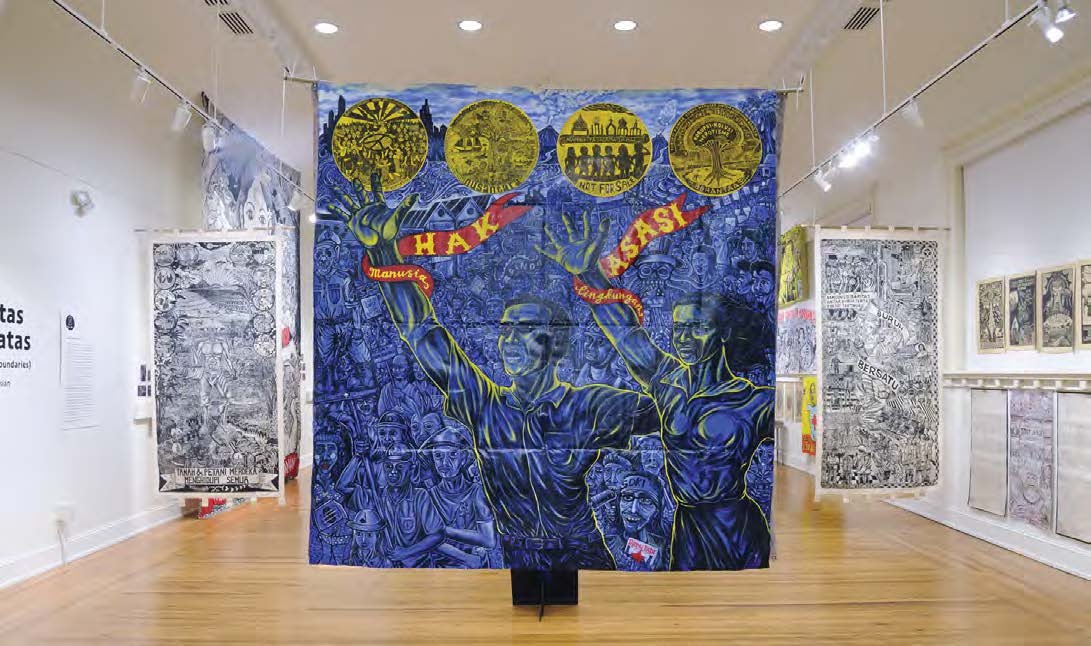

Partial installation view of Taring Padi’s Solidaritas tanpa Batas/Solidarity Without Boundaries at Marketview Arts, York (2021). Photo by Gregory Staley. Courtesy of York College Galleries.

All of the exhibition’s painted protest banners, vast number of woodcut prints, three cardboard puppets, as well as publications, archival exhibition brochures, newspaper cut-outs, and videos of protests in different public spaces originated from Taring Padi’s nongkrong practice, which is often extended to include other communities, such as in the Porong district. The exhibition came about when Marketview director Matthew Clay-Robison hung out with members of the collective in Yogyakarta in 2018. They showed him a copy of Taring Padi: Seni Membongkar Tirani (Taring Padi: Art Smashing Tyranny), a comprehensive monograph that was published in 2011. In addition to excellent articles about Taring Padi, the publication contains reproductions of the visual works they have co-produced and collected over the years. The book became the conceptual backbone for the exhibition at Marketview, which featured impressive banners such as the three-meter-by-three-meter Bumi Manusia (2020). Named after writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s tragic love story set in the oppressive time of the Dutch colonization of Indonesia, the image depicts a half-man, half-woman figure breaking free from chains that extend from an industrialized, militarized, and inequitable environment.

Fitri DK told me that in public spaces, specifically in Indonesia but also elsewhere, Taring Padi artists often appear conspicuous because of their colorful clothes and tattoos. That is why they take time to gain people’s trust through nongkrong in all their projects. For example, when they arrived in the village in Porong, they set up camp close to the village. After a while, the children became curious and made contact. They taught the children songs and after a while the parents came to check on them and hung around. Usually, this is how nongkrong starts in the villages. Then, over the course of a few days, they organized a protest in collaboration with the villagers. Since nongkrong is such a popular practice in Indonesia, other artist collectives that came about in the post-Suharto era, such as ruangrupa, also swear by nongkrong. As the artistic directors of documenta fifteen, ruangrupa established ruruHaus in the center of Kassel as a site for nongkrong years ahead of the event.

Unfortunately, in the past two years, the Covid-19 pandemic has disrupted in-person nongkrong processes significantly. But in 2022, Taring Padi expects to continue to nongkrong and organize a Wayang Kardus Workshop at documenta fifteen in Kassel. What kinds of protest will result remain to be seen.

A carnival with banners by Taring Padi remembering four years of the Lapindo Mud Tragedy in Siring Barat, Porong, Sidoarjo, East Java (2010). Courtesy of ArtAsiaPacific and the artists.

Tekst: Kerstin Winking

This article was originally published in Art Asia Pacific, issue 128, May 2022 and republished with permission.

- Metropolis M - Solidarity and collectivity: Taring Padi in Framer Framed

- NRC - Taring Padi: 'Muslim fundamentalists see us as threat because we are punk'

- Art & Market - A Conversation with Taring Padi

- Taring Padi

Links

Indonesia / Collectives / Art and Activism / Southeast Asia /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Tanah Merdeka

An exhibition with the Indonesian art & activist collective, Taring Padi, reflecting on the concept of land as the object and site of decolonial struggles.

Agenda

Workshop: Wayang Kardus - Struggle and Solidarity with Taring Padi

A two-day workshop by Taring Padi with food, conversations, jamming sessions and the production of cardboard puppets

Network

Kerstin Winking

Curator, Writer

Alexander Supartono

Art Historian

Taring Padi

Collective

Muhammad 'Ucup' Yusuf

Artist

Hestu Setu Legi

Artist