Towards a Perma-Future by iLiana Fokianaki

iLiana Fokianaki’s curatorial text illuminates the context and inspiration behind her exhibition at Framer Framed, The One-Straw Revolution (2024). Read it here on our website.

The search for a more sustainable development in the ‘developed’ world has, so far, been focusing too much on hardware updates, such as new technologies, economic incentives, policies and regulations, and too little on software revisions, that is cultural transformations affecting our ways of knowing, learning, valuing and acting together. The cultural software is, nevertheless, at least as much part of the fundamental infrastructure of a society as its material hardware. – Sacha Kagan¹

In the summer of 2021, wild fires ravaged the suburbs of Athens. I could not leave my flat, because various agents burning in abandoned factories had made the air dangerously toxic. My days were spent indoors with my dog, glued in front of a screen, seeing the fire devour everything. Helpless and still, we both suffered in the heat, with fans humming in the flat; air toxicity forbade the use of air-condition. How ironic it was that a wildfire was forcing us to be more ecological. I had been working on the research platform The Bureau of Care already for two years, but felt suddenly the heavy presence of the elephant in the room: it was unrealistic to discuss care, without including environmental care as the biggest umbrella under which we think all aspects of the ethics and politics of care.

Wildfires have been a phenomenon in various corners of the world for decades, but these last years are the worst on record. Global agribusiness accounts already for destruction of virgin forests, and 11% of global greenhouse emissions. Together with fossil fuel, transport and construction, these are the most disruptive human activities. And yet, we live in a world that wanting less fossil fuel, less extraction, less destruction is still considered somehow an “activist” “radical” position, rather than an existential demand, a planetary practice for all. The Western, so-called “developed” world should bare the brunt of this disaster, since “first gear” economies and their societies pollute more. Unfortunately, the burden of climate disaster is not shared equally, and even more tragically in the West, climate change deniers have planted the seed of doubt against the urgency to change our cultural software. These last decades, an ever-growing part of society believes either that there is in fact very little that we can do to change the current predicament we are in, or that climate change is not as bad as it is portrayed to be. Additionally -and even more worryingly- there is a part of society that believes that climate change is fake news.

Already in the 1970s, the climate crisis and the way fossil fuel and industrial farming contributed to our present ecosystem collapse, were well known by scientists, thinkers, activists and cultural practitioners. Many posed questions towards sustainability and begun looking for methodologies that separate from the modus operandi of the turbocapitalist globalised world that was already apparently forming by the mid-80s. Revisiting texts from that period, it was shocking to see how accurate predictions have been and how many cultural practitioners were probing into ways of avoiding climate disaster. Various seminal texts, researches and methodologies were published on how to operate in non intrusive and polluting ways on both the micro and macro scale. One of them was The One Straw Revolution (1975), an influential book on ecological thought and practice, written by Japanese farmer and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka. The title of Fukuoka’s book refers to the technique of scattering straw in a field post-harvest, following his philosophy of cultivating the earth with minimal waste and respect for preserving ecosystem balance. The method, absent of pesticides and fertilisers, focusing on minimal waste, still holds the solution for the radical challenges in the global system of food production and distribution; an issue that has only grown more urgent today. His methodologies propose a long-term approach, putting prolonged and thoughtful observation ahead of extractive and thoughtless labour, by looking at and learning from plants and animals and all their intersecting behaviours. As a result, his work was among those that probed scientists and academics to further develop this thinking into what today is known as “permaculture.”

A short-cut for ‘permanent culture’, permaculture is a philosophy and practice of working with – rather than against – the ecosystems we are part of and dependent on. It proposes thinking in the long-term, putting at the forefront protracted and thoughtful observation rather than protracted and thoughtless labor, by looking at and learning from plants and animals in all their intersecting behaviours. Permaculture was coined as a term by scientists David Holmgren and Bill Mollison in 1978², their work being in consonance with Indigenous and traditional knowledges, rooted in local cultures, customs and practices. What drew me to look into it more, was the concept of organising through re-wilding, through respect and a profound care and tenderness for non-human animals and flora, embracing interspecies co-existence that supports symbiosis rather than antagonism. Could we apply its working methods in the cultural realm, and think of a permanent culture as one that is sustainable for the future to come? But how can we think of culture and permanence in a world that is currently collapsing?

Exhibition ‘The One-Straw Revolution‘ (2024) curated by iLiana Fokianaki. Photo: Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed.

The exhibition The One Straw Revolution (2024) is inspired by the main principles of such strands of ecological thought and practice, that propagate for a way of being that heeds the existential threat posed by the climate crisis. The works presented explore questions regarding “permanence” and sustainability, deriving from a desire to connect with philosophies and practices operating counter to neoliberal and capitalist models.The exhibition is structured around perma-culture’s zone system, with a focus on zone 0: the human and her settlement, while addressing the spatial philosophy of perma-culture, with a convivial criticality: less anthropocentric on the one hand, more critical of the so far human interventions that brought us where we are today.

Some of the works presented focus on human detachment from nature, highlighting the need to re-script the way we understand our species in connection to the world. Bik van der Pol‘s contribution revisits their work with the Strenkali, a community stretching around the river in Surabaya, Indonesia, fighting for their rights to be citizens and make living alongside the river sustainable. The work from 2015, is in dialogue with a new work developed in Norway, that attempts to trace how Western subjects engage with the world – in particular, how we mine, excavate and otherwise exploit the ground on which we stand. Nora Severios traces her own connections to land and specifically the mountain, through a recalibration of her own identity, attempting to familiarize herself with plant knowledges of her ancestors, while examining the cliche of the Kurds as mountain people, farmers and foragers that live with and through the mountains.

Himali Singh Soin, addresses the mountain as a living organism; a witness of toxic destruction and exploitation by power systems. By using a real-life spy story in the Indian Himalayas to discuss not only environmental catastrophe but also nuclear culture, she highlights toxicity and the grey zone between spirituality and scientific fact, or Western versus non-Western knowledge systems. Irene Kopelman equally delves into power systems, but those that emerge and are entangled with plant life and expansion, tracing the roots of the Cinchona tree that was transported throughout the colonies for the treatment drug for malaria, quinine. Interestingly, Uriel Orlow is focused on another plant that treats malaria, Artemisia afra. He presents not only its past, but its present and future, through non-extractive relationships to natural resources as well as local and sustainable healthcare solutions and forms of solidarity, in countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo whose colonial and postcolonial economy has been dominated by various forms of extraction (mainly of minerals). Denise Ferreira da Silva & Arjuna Neuman’s film essay (the third in a series of fours that discuss the four elements: air, earth, fire, water) questions how colonial, capital, hetero-patriarchal structures of power, perpetuate categorisation and difference, to break material ties to other humans, more-than-humans and deeper implicated bonds with our planet and beyond.

Himali Singh Soin, An Affirmation (2022) in ‘The One-Straw Revolution‘ (2024) curated by iLiana Fokianaki at Framer Framed, Amsterdam. Photo: Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

The legacies and cosmologies of Indigenous communities in South America, still guardians and protectors of any possibilities for a future are apparent through the work of both Edgar Calel and Eliana Otta. Through their presentations for this exhibition they discuss the lives of communities that have been more closely embedded with and affected by nature -and its destruction. The Guatemalan Calel revisits his own ancestry and his connection to both environment and ancestors, while evoking memories of his family and paying homage to the indigenous communities of the midwestern highlands of Guatemala. Similarly Otta, furthers her work on the indigenous community of her native Peru, the Nuevo Amanecer Hawai, based near the town of Satipo, in the Peruvian Amazon. She chooses to describe her experience of sharing life with them, in a form of hommage to the dead leaders of the community, celebrating their legacy and impact in the new generations that continue to defend their way of life and humanity’s possibility to a future. Both practices highlight not only the tropes of living that respect ecosystem balance, but further the philosophies of living together considering non-human centric cosmologies and interspecies kinships.

Edgar Calel, Music for Our Grandmothers and Grandfathers (2023) in the exhibition ‘The One-Straw Revolution‘ (2024). Photo: Maarten Nauw / Framer Framed

Kyriaki Goni discusses the damaging effects of overtouristification through the almost collapse of delicate ecosystems in the Aegean sea, Greece. Proposing current neoliberal systems of cheap and fast holidays, as contributors to our ecological collapse. Through the fictive near-future story of a girl that is tracing the extinction of bees in the Aegean archipelago, ( a real life threat currently in my native Greece) she aims to point towards the senseless damage to ecosystem balance we all participate in through tourism. Similarly, Citra Sasmita’s work is revisiting her native Bali. The once abundant connection with nature, described through traditional forms of art, poetry and literature is evident in large paintings filled with female figures emerging from trees and flames. By using the visual language of tradition and mythology, and visual signifiers of the binary nature/female, she comments on contemporary societal questions that refer to gender equality in her native Bali, but also innate connotations towards our relationship to nature.

The exhibition focuses on thought and practice that aspires for a human and non-human intersectionality and the desire to build on eon-long traditions and mandates of a non-proprietary culture of land and life, connecting a sustainable past with a sustainable future, ancestors with descendants. It also focuses on the legacies of knowledge systems that have been thriving separate and despite of heteronormative patriarchal Western hegemonies and colonial and neo-colonial violence. But it also explores examples and imaginaries of sustainable futures through artistic practices that call for de-growth. As one of the works declares, the aim is for a world to be drafted where subjectivity is unbound from the mind alone, but rebound to the world. The works are spatially composed, so that we re-think our habitat, our home and our immediate surroundings differently.

What The One-Straw Revolution proposes, is that we think of an exhibition as a form of an alternative ecology, in which artworks contribute to shaping what I call a shared perma-future: a future where we exist otherwise as humans in the world, by departing from our catastrophic implication in the Pyrocene and by re-considering our role as fellow ecosystem contributors. In a world that is slowly heading towards collapse, to be able to imagine and contemplate on such a future, through a new cultural software that changes our ways of knowing, learning and being in the planet, can ignite the sparks of a revolution.

iLiana Fokianaki

January 2024

- 1. Kagan Sasha, Toward Global (Environ)Mental Change, Transformative Art and Cultures of Sustainability, Edited by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, (2012) p.14

2. Mollison, Bill, Introduction to permaculture, Tagari Publications Australia, (1991) p.6

- Digital Hand Out - The One-Straw Revolution

Attachments

Ecology / Extractivism / Colonial history /

Exhibitions

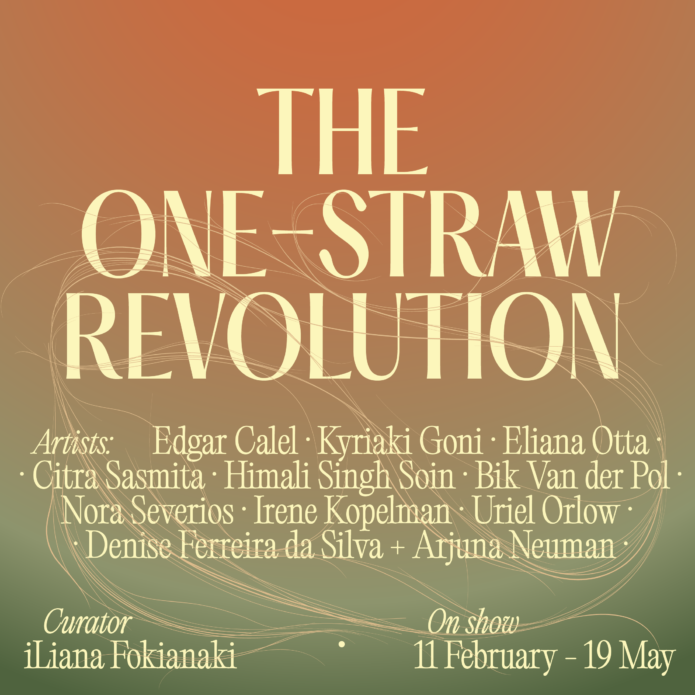

Exhibition: The One-Straw Revolution

An exhibition curated by iLiana Fokianaki exploring permaculture as a methodology for exhibition-making

Agenda

Opening: The One-Straw Revolution

Opening of the exhibition, The One-Straw Revolution, curated by iLiana Fokianaki

Network