The Garden as Material, Map, Metaphor, State of Mind

The exhibition A rising flower makes a garden by artist Ratu. R. Saraswati (Saras) presented at Werkplaats Molenwijk in the winter of 2022 is inspired by the history and the daily encounters with the residents during her stay as an artist-in-residence. Her experience in the neighbourhood has led to a number of proverbs and parables that she shared in the form of a performance during the opening of the exhibition. Curator Megan Hoetger wrote a reflection text based on her visit of the performance and conversations with Saras during the residency period.

Text by Megan Hoetger

In the spring of 2022, I visited the Rijksakademie Open Days with several recommendations from friends and colleagues, and with one thing on my personal checklist: the studio of Ratu R. Saraswati (Saras) where there were to be closed performances periodically across the week. I attended on a Sunday, arriving just in time as everyone settled into the chairs that encircled a large book on a specially-made stand in the centre, which was based on the design of those used for the Qur’an. For something like thirty minutes, we listened to Saras read from her Route of Flowers, a collection of parables and photographs created during her two and a half years living and working in Amsterdam Oost.

The stories she shared combined the phonetic plays of poetic verse and the temporal rhythms of narrativity into a form – the parable form – through which the artist articulates intense questions of commitment to place, to memories, to practices of remembering, and to the durationality of these kinds of commitments. My imagination was captured by her writerly voice and its capacity to weave the everyday and fantastical, structural and spiritual, ethical and aesthetic; by the space it makes – the space that it performatively writes into being – for faith-filled enchantment in the realms of both critical, decolonial analysis and contemporary artistic practice.

—

Six months later, nestled into the Molenwijk neighbourhood of Amsterdam Noord, I met with Saras again as she slowly settled into her fall residency with Framer Framed. We spoke at some length about her artistic research process. Shifting to this Dutch residential area with large housing projects and winding green spaces, as she explained, had already made a significant impact. The studio at the Werkplaats Molenwijk is a warm wedge-shaped workspace with a slanted ceiling and glass wall facing the green space outside.

View of the Molenwijk workspace during a studio visit with Ratu R. Saraswati, 28 October 2022. Photo: © Megan Hoetger

It feels tucked away and, yet, with a parking garage just above and the Molenwijkkamer (a community multi-purpose space) right next door, it is anything but quiet. It is tucked into the folds of the neighbourhood’s social fabric, and, for this reason, particularly well-suited for a practice like Saras’s, which has foundational coordinates in everyday acts of conversation. Such social exchange is at the core of her writing process, as we discussed over tea that afternoon. My questions throughout were led by my interest in hearing Saras’s thoughts and ideas on social practice as a performance form. To my surprise, I learned that her earliest experiments in performance had been within traditions of feminist body art and endurance-based actions. While she’s since moved away from that kind of physically strenuous way of working, the body has remained central in terms of its relationality.

Connecting with others – “the people that I know every day” – and their situated experiences, Saras described to me, is the reason for making art. Underlying the work, I realised, are questions of belonging. Bullied during her childhood and often struggling throughout her youth to feel connection with others around her, her practice has with time become a site from which to explore communication and the vernaculars of belonging: fragility, trust-building, currencies of exchange, common ground: “I’m trying to learn what is the limit of free speech,” Saras said in our conversation. Indonesian cultural cues install a tendency to not speak about things that one does not agree with, she continued, “so how to speak in such situations?” “What are the limits of conversation?”, I asked.

Here another facet of the work enters: her own diasporic positionality in the Global North (the difference between two and four seasons being, in particular, a recurrent embodied point of reference in her writing). Living in the Netherlands as an Indonesian woman and practicing Muslim, many of the conversations she has entered into during her research have either rubbed up against or directly engaged the ongoing presences of Dutch colonial histories, as well as the relation of the Netherlands to Islam and the heterogeneity of Muslim Dutch identity. How do we really find common ground in practices, much of her writing ruminates on, unfolding the gaps and schisms between how we learn to act toward others in principle and how we actually act toward others in practice.

A shared sense of space is one of the primary ‘currencies of exchange’ that the garden has offered for Saras, during her time in Amsterdam Oost and especially here in Molenwijk. It has also brought the artist a renewed awareness of the embodied mapping practices that she has been cultivating since re-locating to the Netherlands.

How does one map a new place?

Create a picture of it so she knows where to go and not go?

Draw routes through it?

Bird songs versus territory lines.

The plants and the gardens, their seasonal cycles of bloom and decay, and practices of carrying for them have been ways of entering this new place through affective points of reference, which move fluidly between ‘the world out there’ and ‘the world in here’ of the artist’s imagination. Sketching out a personal psycho-geography of the neighbourhood, Saras used her time in Molenwijk to establish ongoing dialogues with a range of residents: Annie, a neighbourhood resident for 32 years (originally from Friesland) and founder of the Wipmolentuin community garden 30 years ago; Hella, another resident working with Annie in the garden; Toon, a neighbour who frequents the Molenwijkkamer; and Muhammad, a municipal gardener tending to the green spaces around the neighbourhood outside the garden. I left with the intention of returning for the final presentation at the conclusion of her residency, when Saras would share a new performative writing piece penned over the course of her time with these new conversation partners.

Six weeks after that afternoon conversation with Saras, I entered the workspace again, this time for the opening of A Rising Flower Makes a Garden (Saras’s final presentation for the residency). I was met by a walled-sized photographic print suspended from the ceiling in the middle of the room with chairs and a long line of flower prints stretched across the floor in front of it.

Installation photo from the exhibition A rising flower makes a garden (2022) at Werkplaats Molenwijk, Amsterdam, Ratu R. Saraswati. Photo: © Ratu R. Saraswati

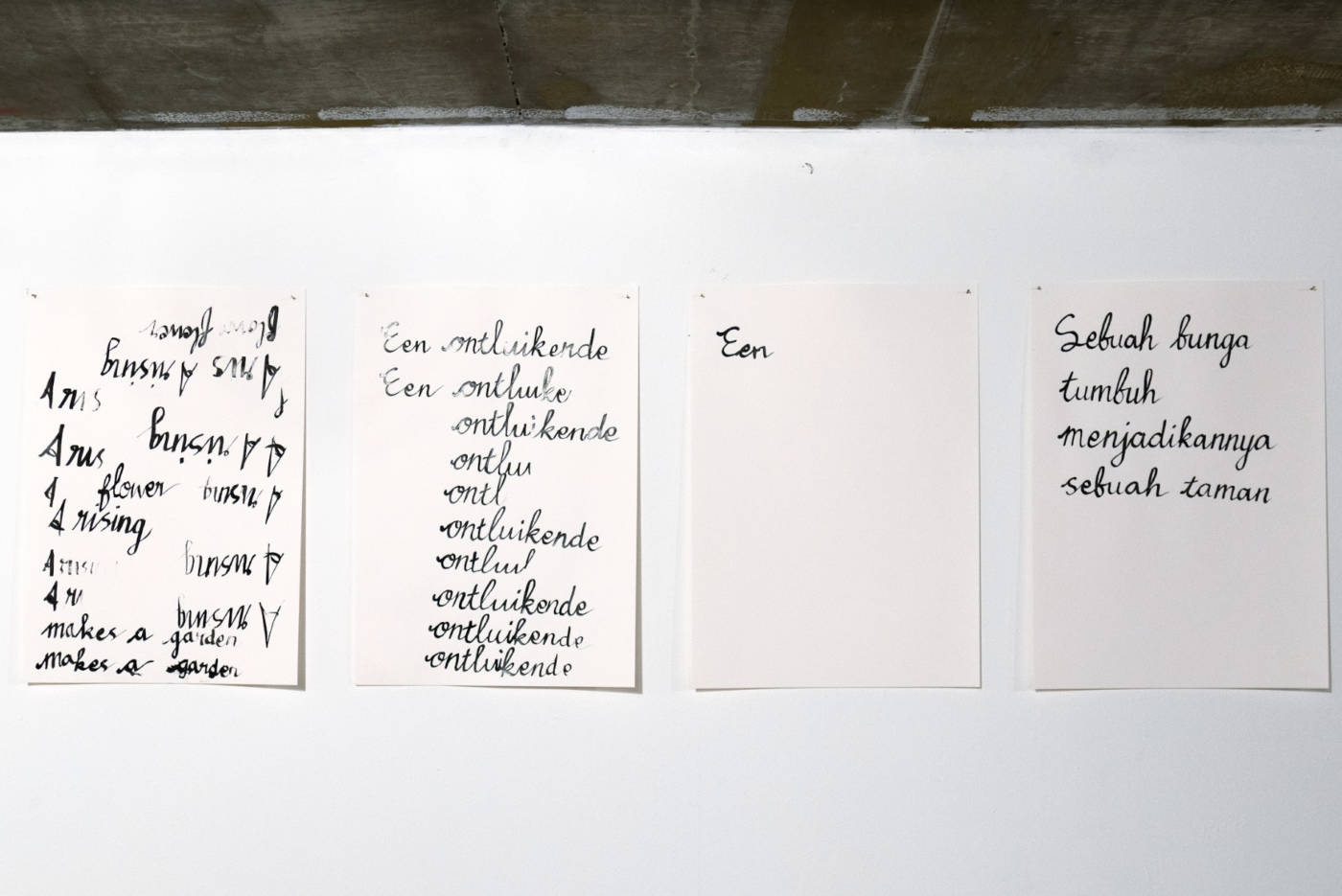

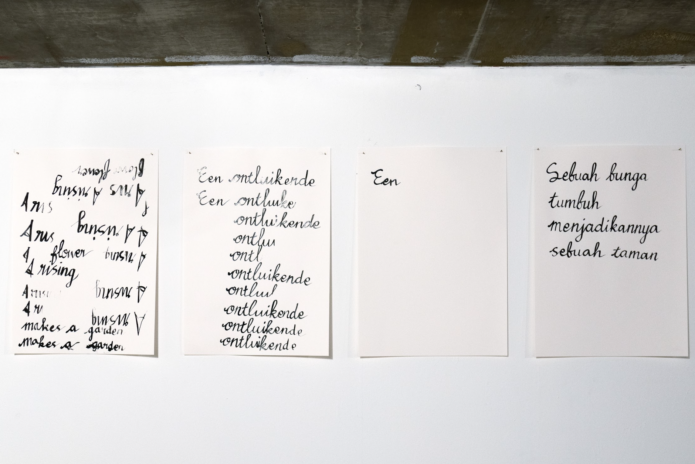

On one side of the print was a large-scale image of the back side of a rose taken from below so that viewers looked up into the infrastructure of the rose’s sepal and stem – into its ephemeral yet robust infrastructure. On the other side of the print was a photograph of the top side of the same rose with its luminous and lush pink petals in that golden moment of early bloom. Printed in the smaller scale, versions of this image were also left in a stack near the wall with the invitation for visitors to take one. In the corners of the room were pinned up sheets of drawing paper with Dutch words carefully written out in black ink – practice sheets. From the floor all the way up to the ceiling, then, the studio became a kind of garden mapped. It also became, that day, an environment within which Saras performed her new writing as a script with lyrics and recitations, exegetic notes and parables woven together.

Installation photo from the exhibition A rising flower makes a garden (2022) at Werkplaats Molenwijk, Amsterdam, Ratu R. Saraswati. Photo: © Ratu R. Saraswati

Installation photo from the exhibition A rising flower makes a garden (2022) at Werkplaats Molenwijk, Amsterdam. Photo: © Lina van den Idsert / Framer Framed

Steel pots make a fence

Brick stacks make a wall

Tooth rows make a fort

And a fellow suggested to her, “Rest your tongue.”

“But I think my tongue is bigger than my mouth.:

“How do I rest my tongue?”

“Should I stick my tongue out?”

First rice field passed

Second sea passed

Third coconut tree passed

Fourth day passed

Firth year passed

Sixth decade passed

Seventh century passed

—Excerpt from Parable of the Tongue by Ratu R. Saraswati

“You are living in the North now, the North has four seasons. Not like in our homelands of South, there we have two seasons,” he continues explaining to her relentlessly and then leaves with more footsteps everywhere on the ground.

She is shocked, once again, grieving for the loss of flowers.

—— The falling leaves cover land

—— The falling leaves cover paths

Not all the falling leaves fall into place.

Not all abundance falls into place.

This abundance is everywhere, overwhelming. It takes such patience to orientate yourself.

**

Since we are talking about paths… Do you know the path that is formed by repeated walks of people when they find a route the is more convenient to them, the most practical route? In English, they called it the desired path, in Dutch they called it een olifantepad, the elephant path. Hannah brought this up to me in our conversation in Werkplaats a while ago.

And then it raises a question for me. The elephant is not native to this continent, Europe. Their habitat is in Asia and Africa. I wonder, how do they, the people who invent the phrase, know very well about the path of elephants?

They must have been there long enough to know about the elephants’ life.

—Excerpts from Parable of the Falling Leaves by Ratu R. Saraswati

The falling leaves cover paths.

Leaves in many shapes and different colours overlap in many layers. I did not see the path.

The abundance is overwhelming, I need to orientate myself.

On Monday, while helping Annie and Hella in the garden, I ask Annie if I can step of the path. She says I can. It makes sense because I help to tend the shrubs and other greenery that spreads over the whole garden. I told myself I need to watch my steps so I will not step on the plants. While being there, I feel the garden immersively. I realise that I breathe among living beings.

— Excerpt from A Rising Flower Makes a Garden script by Ratu R. Saraswati

During her time in the Framer Framed residency, the artist was able to push to another place, experimenting with her layering of writerly voices, with permeating of genre boundaries, and with how to generate new kinds of density in her articulation of experiences. Alongside the move to Molenwijk, which exposed her to dialogues with many different kinds of people outside ‘the centre’, a trip home to Indonesia (the first more than two years) was also personally grounding. In particular what I noticed – and what Saras herself spoke to me about the week after the performance – was a new kind of confidence to speak into and from the different situated positions that she holds in her body about the relational forces that organise, undo, nurture and challenge her.

The use of first-person throughout the performance script, as well as the introduction of the names of her interlocutors (including myself), shifted the work from recitation of a parable to an encounter with a storyteller. If the parable as a form is an extrapolation from experience that is placed outside the individual, the storyteller as an embodied position of witnessing holds the possibility to weave in and out, using parables amongst other forms to track big questions about humanity, relationality, and spirituality through small moments of poetic – and at times quite practical – observations on how to relate to an/other.

The storyteller – Saras – is immersed in the garden. She is immersed in the intergenerational and cross-cultural relationships with Annie and Toon and Muhammad, absorbing new vocabularies and the world-views they articulate. With her and her fellow travellers, we move between metaphors of the path and its materiality. We also move between metaphors of communication and its materiality. ‘The limits of conversation’ that Saras and I had discussed earlier in the fall is still something I am thinking about in regard to her research, and it is still an active element in her writing – the swollen muscle of communication and the grappling with what to do with it, which is made palpable in the Parable of the Tongue, makes this clear. It’s also made clear in the opening lines of her performance script: “I’d like to start by sharing a prayer from the Prophet Musa, or Moses, or Moshe. I’ve always said this prayer in my heart when sharing stories. ‘My Lord, expand for me my breast [with assurance] and ease for me my task, and untie the knot from my tongue. That they may understand my speech.’”

At the close of her residency, I got to know Saras’s readerly voice better, and it is here that I would like to close this field report: by returning to the faith-filled enchantment of the artist’s performative writing and offering a few preliminary thoughts on the kind of pedagogical encounter that is, with time, emerging from it. In our last conversation before the end of 2022, Saras spoke about a shift in her writing form, from the parable to the Ceramah, which is a form of oration within Islam in Indonesia that she describes as somewhere between the sermon and the public lecture. The Ceramah is not a sermon – that is too Christian of a reference point. It is also not a lecture – that is too classed within regimes of educational industrial complex.

The more Saras described to me, the more I was reminded of what I know as Jumu’ah, which is a weekly gathering at the mosque on Fridays, replacing normal the mid-day prayer (Zhuhr) with a pedagogical lesson from the khatib/the imam. My partner often attends Jumu’ah, especially in moments of psychic or spiritual crisis, so I know it as a space of collective healing. I imagine Ceramah to have a similar role. Perhaps I am wrong; but in any case, I think what is shared across these two spaces of address is an understanding of a collective something that can happen in what Saras expressed as “the shared publicness of the mosque”. The depth of feeling with which she is able to tap into this tradition – her own tradition – of “shared publicness” through the garden (as a material, a map, a metaphor and a state of mind) opens up a much-needed space for faith and/as an ethics of belonging in the secularised ‘currencies of exchange’ within much of contemporary artistic practice. It’s not an easy path, for sure; but, as Saras reminds us: “It takes such patience to orientate yourself.”

— Megan Hoetger

Amsterdam, 2023

*You may find the script of Saras’s performance in the attachment bellow. The full video of the performance and more photographs of the opening can be accessed via the website of Saras.

Indonesia / Amsterdam Noord / Molenwijk / Residencies / Social Practice /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: A rising flower makes a garden

By Werkplaats Molenwijk artist in residence Ratu R. Saraswati (Saras)

Network

Megan Hoetger

Curator, Researcher