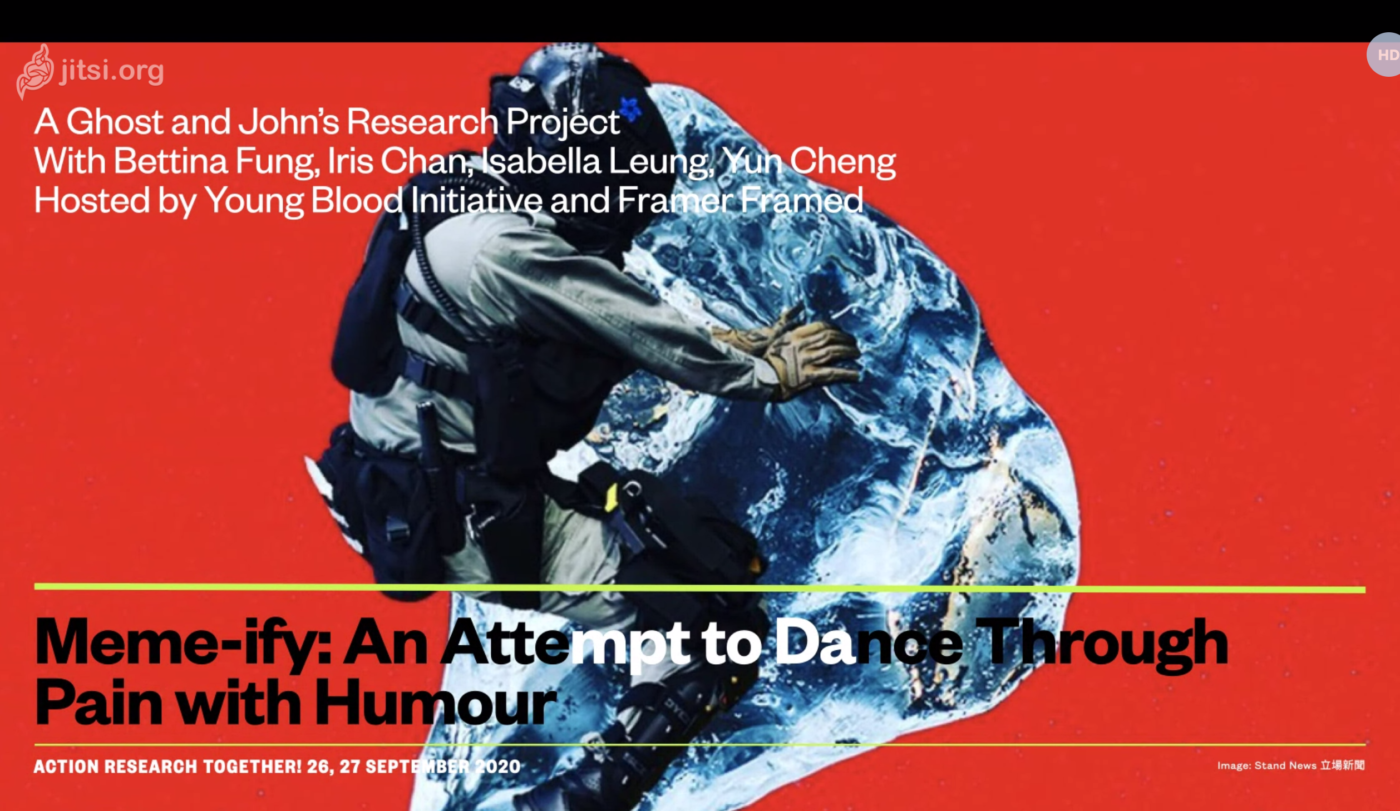

Image provided by Ghost & John. Still by Hao Zhang, Unsplash

Image provided by Ghost & John. Still by Hao Zhang, Unsplash Report: Meme-ify: An Attempt to Dance Through Pain with Humour

by Emily S. J. Lee

September 2020

In face of ever-escalating threats of authoritarianism, neo-liberalism, and nationalism, how do we continue to keep up hope and passion? How can we overcome our physical/mental fatigue and re-commit ourselves when values of democracy, human rights, freedom of speech are failing on many fronts in different parts of the world?

The two-day online action research Meme-ify: An Attempt to Dance Through Pain with Humour, created by HongKongnese artist duo Ghost & John and co-hosted by Framer Framed and Young Blood Initiative, demonstrated that memes can be a form of (self)care and generate relational understanding when used to promote activism; it also emphasised that art can connect a community of kindred spirits in pursuit of alternative visions of politics.

First Impressions of Memes

The first day of the action research, Ghost & John, together with the core research team, introduced themselves and outlined the main objectives for the two-day event. Ghost & John prioritised creating a virtual space where people felt safe and comfortable interacting and sharing opinions. Facilitating openness, both bodily and mentally, was also important throughout the process.

Therefore, after a round of introductions, participants were invited to experiment with their space by either moving away or coming closer to the computer screen, while simultaneously using their body parts or objects nearby to continuously follow along the edges of the computer screen. This unfamiliar method of engagement with the screen not only created awareness of how people are physically bounded yet virtually connected, but also tellingly illustrated participants bodily agency in manipulating and transforming the space around them.

Participants exploring their bodily presence in relation to the physical and virtual space.

Coming from the US, England, Hong Kong, and the Netherlands, most people attended the event because they were curious about combining activism with humour, wanted to think about activism collectively from another point of view, wished to exchange opinions on memes and activism, or simply desired a moment to relax before continuing their own activist battles. When asked about first impressions of memes, people responded with the following:

“Love memes! its magic of clicking on my brain and making me laugh. Memes connect people.”

“Meme is very powerful to forget about anger and sadness sometimes. It makes things absurd and continue me to focus on the objective side of the situation.”

“Memes are easy, funny, but sad. They require a lot of brain power to fully understand, but intriguing enough to keep thinking.”

“I love them and believe there’s a huge political and activist potential.”

As cases studies subsequently shared during the action research process proved, memes are influential cultural elements. Represented by images with overlaid bold captions and shared on social media, memes communicate urgent issues with an amusing touch, becoming one of the main ways for Millennial users to quickly learn and grasp popular opinions about social issues.

Memes in Different Occasions

The Ministry of Health and Welfare in Taiwan created a series of memes of Zongchai, Taiwan’s coronavirus “spokesdog.” Image credit: Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan.

Memes can be used by different agents. For instance, Taiwan has been lauded for its successful efforts at combating the pandemic with the help of Taiwan’s digital minister Audrey Tang, who, using “humour over rumour”, implemented memes across governmental departments. To fight Covid-19 misinformation, her team assisted the Health Ministry in creating memes that feature an adorable Shiba Inu dog named Zongchai (a pun that translates to “chief Shiba” and “chief executive”) as a Covid-19 communications ambassador. The cute dog routinely appears in official platforms to deliver health messages to the public, easing the psychological tension created by the pandemic while simultaneously communicating serious and trustworthy information.

Hong Kong news media Apple Daily post on their Facebook. Image credit: Apple Daily.

As officials use memes to spread information, news media companies also incorporate memes to capture readers’ attention. This summer, Hong Kong Chief Secretary Matthew Cheung, instead of giving a constructive response to the unemployment rate exceeding 15% amongst new graduates, stated instead that young people should lower their expectations in order to chase their dreams: “Even dishwashing is a kind of work experience”.

Not long after the conference, Apple Daily posted an article about this incident on their Facebook using a meme as their cover image.[1] The meme shows Secretary Cheung against a bubbly background wearing a huge bowl on top of his head, while students on the right toss their bowls (hats) as a symbol for graduation. The image wittingly catches the focal point of the statement and its absurdity, revealing how memes convey messages in an effective and entertaining way.

Memes as a Form of (Self)Care

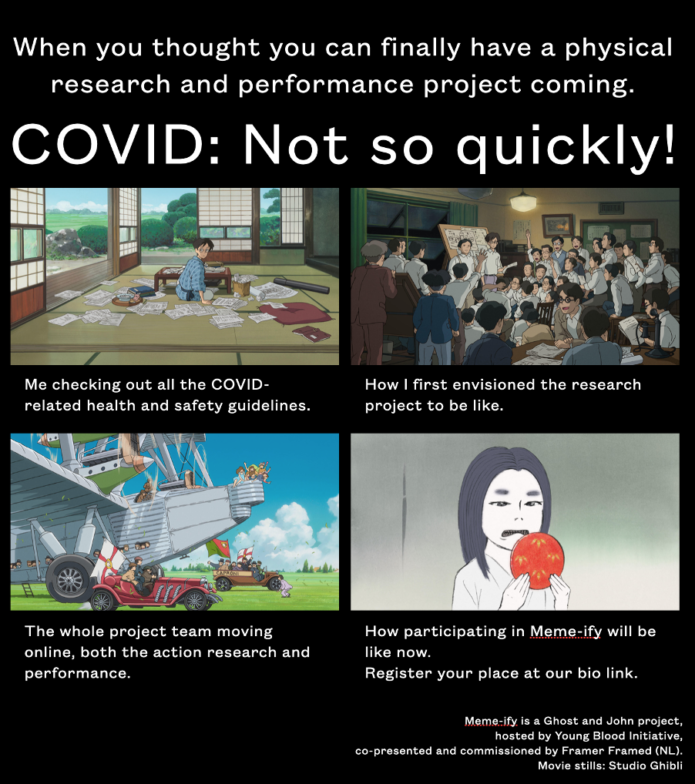

At the end of the first day’s event, Ghost & John took the current viral meme circulating in Taiwan and Hong Kong, where netizens (citizens of the net) create a wide variety of memes using still images released by the Japanese animation company Ghibli, and invited participants to take 20 minutes to create their own memes.

A meme example created by Ghost & John for the action research project. Still by Studio Ghibli.

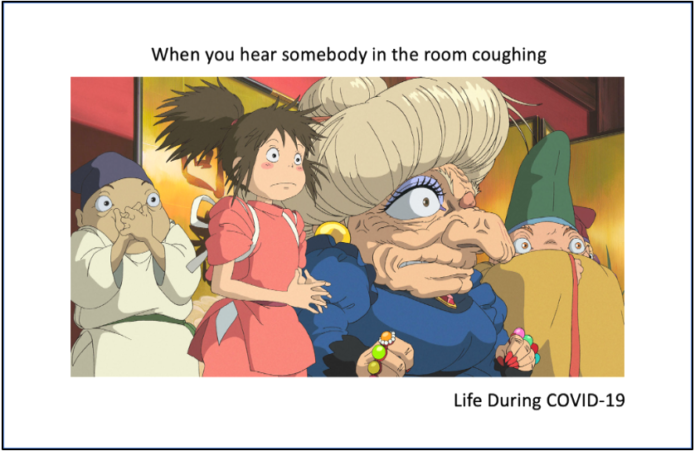

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie Spirited Away (2001) directed by H. Miyazaki.

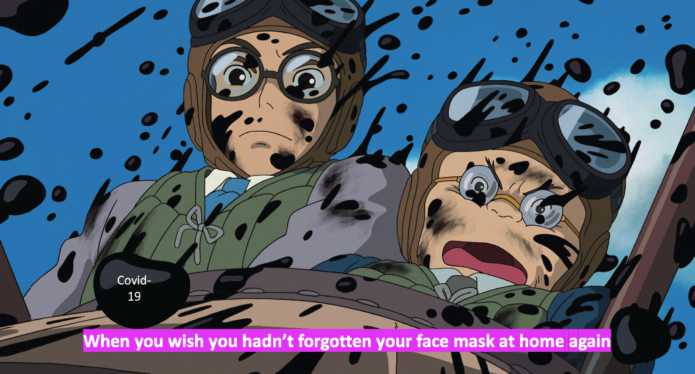

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie The Wind Rises (2013) directed by H. Miyazaki.

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie Spirited Away (2001) directed by H. Miyazaki.

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie Spirited Away (2001) directed by H. Miyazaki.

Image credit: Linn Phyllis Seeger. Still from the movie Spirited Away (2001) directed by H. Miyazaki.

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie Spirited Away (2001) directed by H. Miyazaki.

Image credit: participant from the action research event. Still from the movie The Wind Rises (2013) directed by H. Miyazaki.

As might be expected, many memes related to the pandemic and the social movements in Hong Kong and other parts of the world. However, for most participants, creating memes was considered a self-reflexive, personal procedure rather than an act of protest or a desire to engage with public discourse. One participant noted,

“When making memes I look for things that you wouldn’t normally talk about in a polite society, searching for ideas and desires that are more linked to subconscious desires and feelings rather than rational analysis.”

Another participant regarded creating memes as a form of self-care/reflection, as a process that first relates to oneself, then as a form of activism.

While memes today are commonly used as a cultural reference to sensitise people and attract attention, memes also create spaces for emotions that are fragile and sometimes inarticulable. Memes can be tools for entertainment, market promotion, social movements, but they can also be ways to process feelings and generate care for oneself or within a community.

“Memes evoke a sense of intimacy or complicity, creating an imaginative space where people can laugh or mourn about issues collectively, but also privately.”

This recognition as a form of (self-)care demonstrates that memes embody a profound engagement with the world: they are a product of intellectual and emotional competencies. The reaction of the participants also implies an urge to look after oneself and others. In other words, meme creation allows people to dance through pain with humour as described by Ghost & John.

Memes as a Form of Activism

Memes made by netizens to support #BoycottMulan. Image provided by Ghost & John. Still from Mulan (2020) produced by Walt Disney Pictures.

On the second day of the action research event, participants were invited to take detours in exploring how memes have been strategically used as an activist mechanism and investigate how we may derive performative actions from these memes.

For #BoycottMulan, memes were created to protest the Chinese-born actress Liu Yifei, who, staring in the 2020 live-action remake of the Disney animation Mulan, shared a public post on her social media in 2019 to support Hong Kong police. She wrote, “I support Hong Kong’s police, you can beat me up now. What a shame for Hong Kong”.[2] Later, people learned the movie was partly filmed in Xingjiang, where Uighur continuously lives under oppression. There were also discussions pointing out how the film misrepresented Chinese culture, producing more controversies and debate.

While the initial intention of the #BoycottMulan memes was to actively discourage people from watching Mulan, some people feared the memes would actually help promote the film, encouraging the public to watch it based on curiosity. This contradictory force of memes, as for all political progressions through media and art, risks generating division, antagonism, and frustration within activist communities. Hence, recognising the potential contradictions and complexities when using memes in political activism is essential; only then are people able to formulate ways to better communicate the medium’s multi-directional impact.

As shared by some participants, people may watch Mulan not because they are ignorant, but because they want to learn what went wrong to form a solid opinion. Furthermore, even if activist memes partially promote rather than downplay opponents, it is undeniable that their popularity and visibility create new entry points for people to be more engaged and willing to learn about otherwise unfamiliar topics.

Memes, like language, are a mode of production created in a specific social/historical situation that produces communication and makes connections. We need to practice this language and understand how it is used to construct connections that can create positive change. At the same time, constantly reflecting on our own intentions and consequences when using memes as activist tools is crucial. We must consider our own position in a contextualised matter with regard to social movements (e.g., Black Lives Matter, Covid-19, climate crisis, Hong Kong) to avoid coercion or discrimination.

While the first day of the event revealed how memes can be a form of (self-)care, #BoycottMulan suggests that a careful and relational understanding is necessary when memes are used for activism.

Memes as Inspirations for Performative Action

The weekend action research, originating from a simple wish to combat activist fatigue and the absurdity of current affairs, correlates with what philosopher Rossi Briadotti discusses about Democracy Fatigue in our contemporary society. She writes,

“Anger and opposition alone are not enough: they need to be transformed into the power to act so as to become a constitutive force. The crucial question is: who and how many are ‘we’? Resisting the bellicose appeal of the people, I argue that politics begins with assembling just a people, a community constructed around a shared understanding of their condition. This space of encounter is also where forms of action can be produced, about our shared hopes and aspirations. Critique and creation work hand-in-hand.”[3]

While art activism is mostly linked with rage, depression, and frustration, the two-day action research event created a safe and hybrid space, where people from all over the world encountered and collectively explored the endeavour to “embrace the negativity of the suffering world, and transform it into active creation of alternative worlds”.[4] The event reminds us that art is a form of building, a joining together, a productive gesture. Starting from a virtual space, art connects a community of kindred spirits in pursuit of alternative visions of care and politics.

*We would like to thank all of the participants who joined the event and their creative contributions.

[1] Apple Daily. University graduates can try dishwashing to gain work experience: Hong Kong Chief Secretary. https://hk.appledaily.com/news/20200823/TZNXEN4XHVBN7IEHOJPBID5SMM/

[2] BBC News. Liu Yifei: Mulan boycott urged after star backs HK police. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-49373276

[3] Rossi Braidotti, R. 2019. Posthuman Knowledge. Cambridge: Polity.

[4] Puig de la Bellacasa de la Bellacasa, María . 2017. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press.

Citizenship / Action Research / Art and Activism / Politics and technology /

Agenda

Meme-ify: An Attempt to Dance Through Pain with Humour

Online Action Research Workshop

Network

Candy Choi

Founder of Young Blood Initiative