Essay: Peeling onions as an archive of gesture, memory and resistance

Scholar, curator, and archivist Almudena Escobar López reflects on the exhibition Remembering Otherwise (2025), belit sağ’s solo exhibition at Framer Framed about a 1978 strike by sixty-five migrant women from Turkey in a Dutch onion-peeling factory in Veghel. Almudena traces how Remembering Otherwise and its central film Layers of a Dispute rethink what counts as an archive of labour struggle. Moving between close readings of belit sağ’s images, gestures and textiles and a dialogue with Harun Farocki’s politics of the image, she shows how memory is carried through bodies, smells, jokes and inconsistencies rather than official documents or linear timelines. The text argues that sağ’s work refuses the demand for definitive testimony or historical closure, instead proposing a fragmented, relational and embodied mode of remembering that centres migrant women’s experiences in Veghel as sites of both vulnerability and resistance.

Text by Almudena Escobar López

December 2025

In Remembering Otherwise, a solo exhibition by Amsterdam-based artist belit sağ (she/her and they/them), the point of departure is a 1978 labour dispute in Veghel, where sixty-five migrant women from Turkey walked out of an onion-peeling factory in protest against suffocating conditions and piece-rate pay. Rather than reconstructing that strike as a linear story, sağ works with video, textile, collage and storytelling; she highlights a feminist and diasporic approach to remembering, revisiting one of the earliest unionisations by migrant women in Dutch labour history. They layer fragmented voices, bodily gestures and tactile materials to emphasise how memory is shared, embodied and contingent. Far from aiming to ‘correct’ the gaps in the institutional archive, sağ challenges how history is made legible. Influenced by but distinct from Harun Farocki, they shift the focus from surveillance and analysis to intimacy and gesture. What emerges is not a “living archive” in the overused sense, but a method of historical inquiry rooted in slowness, relationality, and collective storytelling—one that recognises the friction between fact and feeling, memory and material.

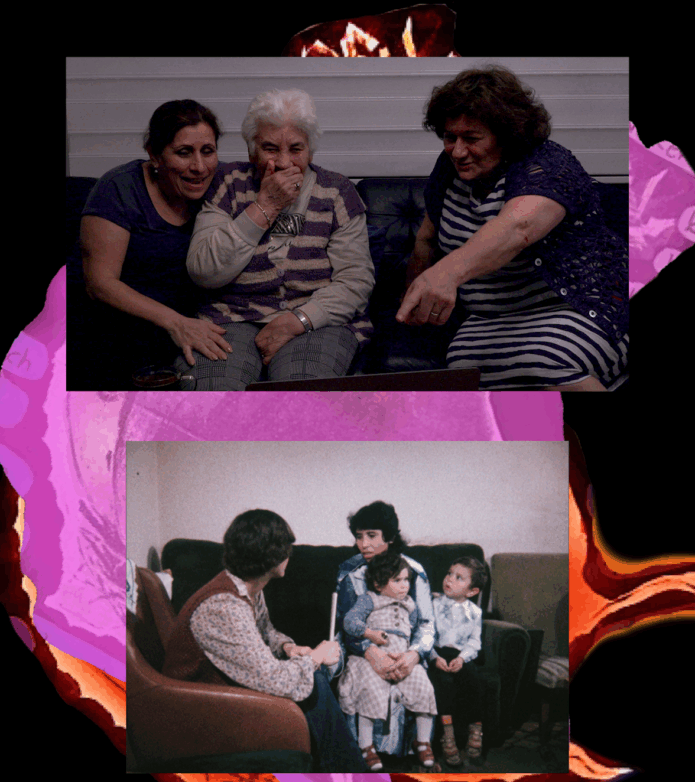

In Layers of a Dispute, the main film of the exhibition sağ constructs a visual essay that challenges the usual interview style often demanded of historical representation. The film is not a documentary in the traditional sense. It offers no clear timeline, no guiding narration or definitive interpretation of events. Instead, it develops through translucent layers: an onion skin, both literal and symbolic, becomes the structural basis of the video. sağ overlays interviews, photographs, textures and voices, eliminating the single authoritative voice. The past appears in fragments and flickers—never as a stable image, but as something to be felt or inferred. The onion is not only the object of labour around which the women’s strike formed, but its layered materiality, peelable but never fully transparent, becomes a metaphor for memory itself.

In one moment of the video, one of the former workers, Nazife Kaya, also reenacts the peeling gesture. Her motion is slow and deliberate, tightly framed by the camera. It is not merely a reenactment but a form of embodied memory where knowledge is expressed through muscle and repetition rather than language. The body recalls what institutions forget. This moment recalls Harun Farocki’s exploration of the body as a site of inscription for power. In Workers Leaving the Factory (1995), Farocki examines over a century of images depicting workers leaving factories, a day of hard work behind, gestures repeated over time but rarely examined. Like Farocki, sağ is attuned to the micro-gestures of labour, though their approach is less analytical and more intersubjective. If Farocki’s camera dissects, sağ’s dwells. If Farocki reveals structure, Sağ reveals presence. Where Farocki maintains distance, sağ’s camera is intimate and engaged.

Farocki’s films are often diagnostic, mapping how the logics of capital produce particular bodily comportments. sağ, while influenced by this analytic framework, moves instead toward a tactile aesthetics of remembering. Their interest lies not just in the visibility of labour but in the sensation of it: the gossip exchanged, the awkward silences, the smell of the onions. These are not just backdrops to political struggle; they are the politics. This emphasis on the minuscule, the sensory and the interpersonal marks a crucial divergence from Farocki. He presents his concern with the politics embedded in the system of gestures, whereas sağ is attentive to how gestures themselves produce memory and the ways in which they serve as a form of historical narration when language fails. Moreover, sağ’s engagement with the women’s recollections never collapses them into a collective voice or testimonial clarity. The stories told are inconsistent, even contradictory at times – more concerned with who was angry or who gained weight than with definitive accounts of what happened. This, again, is a refusal of the archival logic that prioritises verification over texture. What matters is not the accuracy of memory, but its affective charge and its ability to carry emotion, friction, and attachment. sağ’s approach recognises that the archive is more than what is written or recorded; it also includes that which circulates in gestures and glances. Layers of a Dispute critiques the archive by offering an alternative mode of presence: a fragmented, relational and embodied form of memory.

Another striking feature of Layers of a Dispute is sağ’s own voice. Her voice accompanies a viewer, sometimes doubting, sometimes clarifying – often reflecting instead of guiding or explaining. Their presence models an ethic of proximity: being close enough to care, but not so close as to consume. sağ’s voiceover does not claim access to truth but creates a reflective space for the viewer, a space that calls for active listening. This relationship with the voice differs significantly from Farocki, who rarely used his own voice and often adopted a third-person, distant mode of address. sağ’s work prioritises interruption, pause, and intimacy. Their voice functions less as a narrative thread and more as an echo or resonance, inviting the viewer to sit with the uncertainty of memory. sağ mobilises voice and gesture not to fill in the archive’s gaps, but to dwell in them. This is perhaps her most radical gesture: resisting the demand to repair or complete the historical record. Instead, she reorients attention toward what remains when history fails to cohere. For the women of Veghel, this is communicated through affect, sensation, bodily knowledge, and the residual traces of their experiences.

The Material Politics of Textiles

Whilst Farocki often drew on surveillance footage, training videos and institutional media to dissect the mechanisms of labour and control, sağ turns to materiality, particularly textile, as a mode of historical intervention. Based on archival fragments, the monumental tapestry in Remembering Otherwise is not simply an aesthetic object but a public display of overlooked labour histories. Installed at the Amsterdam East Municipality Office, the tapestry re-situates these forgotten stories within the bureaucratic architecture of the state. Its physical scale and public placement assert the importance of women’s work in historical and spatial terms, connecting the past with the present geography of migration in Amsterdam. In opposition to the anonymous, sometimes mechanised spaces of archival video footage, sağ brings us back to specificity, locality and texture.

Textiles are inherently tied to gesture: they are made by hand, over time, through repetitive motions. Due to this, the tapestry becomes a memory object, reflecting the labour of both the onion peelers and the artist herself. Its size and visibility in a civic space challenge the invisibility of women’s labour and make history felt through its grand scale and colourful presence.

sağ’s choice of textile production harkens back to her heritage in Turkey, where weaving has historically been seen as a gendered, domestic craft. By linking the cultural tradition of weaving with the manual labour of onion peeling – also assigned to women – sağ draws a political connection between embodied labour and what counts as political struggle. In her work, a cooking anecdote or a poorly ventilated factory space becomes just as historically significant as a strike vote or a union contract.

Additionally, sağ’s use of collage reflects their broader critique of how archives function. Their images are often layered, fragmented, or cropped. She avoids citing sources directly, even when quoting, deliberately disrupting the systems that assign value and legitimacy to archival materials. The effect, from both a political and aesthetic choice, is one of radical de-hierarchisation. What matters most in her presentation is not provenance, but resonance. They bring together quotes, images and recollections that may not appear to “match,” allowing viewers to make their own relational associations. This method aligns with broader feminist archival practices, where what is excluded – what is unspoken, residual, or deemed trivial – is brought to the forefront. By amplifying the sensory and the anecdotal, sağ repositions gossip, touch, and smell as important forms of historical knowledge.

An Archive Without Authority

The strike at the Veghel factory was not a moment of perfect clarity but exhaustion and resilience, as labour struggles are. Through collage and films, sağ honours the complexity of the labour dispute, refusing to streamline these experiences into a singular narrative. The tapestry itself is a practice of friction, weaving together different fabrics and memories in an intentional resistance to coherence and linearity. sağ’s edits are stitched together in a way that shows their seams and textures, mirroring the instability of the events being remembered. Importantly, sağ avoids positioning themselves as an authority. In their hands, the archive is not something to be restored or perfected. It is a space to be inhabited, disturbed and reconfigured. It is about sitting with uncertainty, sharing space and attending to the materiality of memory. This is what makes her approach so radical: not that it recovers what was lost, but it refuses to pretend the loss can be fully repaired.

Remembering Otherwise stages a collective act of remembering. But this is not about recovering a singular truth. Instead, it is about producing knowledge collectively, through overlapping stories, gestures, pauses, jokes and fragments. The women interviewed do not merely recount—they perform memory. They do not provide perfect testimony. Often dismissed as tangential, their stories are central to how labour is experienced and remembered. sağ’s camera does not extract these memories. It stays close. It observes arms, shoulders and the light of a room. It mirrors her subjects without absorbing them. This refusal to finalise, to translate memory into official discourse, is itself a political gesture. It allows history to remain open, relational, in-process. These memory performances, through gesture, voice and body, become techniques of resistance against dominant forms of historical narration. The re-telling is not a supplement to the archive but a rupture. sağ’s focus on trivial details – the smells, the gossip, the bad cooking – suggests a different value index. And sağ, by structuring these performances into layered visual essays and tactile forms, builds a method of historical inquiry that is both conceptual and affective. sağ offers modes of re-seeing, re-feeling and re-connecting—where the archive becomes a site of negotiation, not resolution.

Remembering Otherwise

Ultimately, belit sağ’s Remembering Otherwise reconfigures the ways in which history is seen, felt and shared. Through gesture, textile, voice and storytelling, sağ critiques institutional archives not by negating them, but by exposing the limits of their narrative logic. Influenced by, but distinct from Harun Farocki, sağ centres the affective, the intersubjective and the relational aspects. Their interest is not in portraying labour as a static image but engaging with labour struggles as a dynamic process of memory and meaning-making.

In Layers of a Dispute, sağ shows us that labour politics are not always legible in slogans or statistics. They are also found in the texture of an onion skin, the rhythm of a shared memory, the awkward reenactment of a forgotten gesture. These are not footnotes to history; they are its foundation. Rather than reconstructing a coherent past, sağ offers a methodology of attention: to gesture, feeling, and fragmentation. In this space between archive and experience, between seeing and sensing, new forms of solidarity and resistance may emerge.

belit sag, ‘Weaving Solidarity‘ (2025). Textile 7m x 3.5m

Feminism / Diaspora / Shared Heritage / The living archive / Textile / Turkey /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Remembering Otherwise

Solo exhibition by artist belit sağ in collaboration with curator Katia Krupennikova on a pivotal 1978 labour dispute led by migrant women workers from Turkey

Agenda

Opening Exhibition: Remembering Otherwise - OBA De Hallen

Opening of Remembering Otherwise by belit sağ in OBA De Hallen, with an introduction by district mayor Fenna Ulichki, musical performances, readings and a panel talk with the artist

Network

Almudena Escobar López

belit sağ

Artist, Educator

Katia Krupennikova

Curator