Interview with the Burning Museum Collective

Burning Museum is a collaborative interdisciplinary collective rooted in Cape Town, South Africa. Burning Museum departs from the contention that the space we find ourselves in is one which has been scarred and seared by a historical trajectory of violent exclusions and silences. These histories form the foundation of an elusive and at times omnipotent democracy that occasionally reveals its muscle in the form of laws and by-laws in public space. It is from this historical climate and present context that the work of the Burning Museum engages with themes such as history, identity, space, and structures. Burning Museum is interested in the seen and unseen, the stories that linger as ghosts on gentrified street corners; in opening up and re- imagining space as potential avenues into the layers of history that are buried within, under, and between.

Burning Museum creates on-site work for Re(as)sisting Narratives

Burning Museum’s work in the exhibition Re(as)sisting Narratives (2016) will be newly-created. The collective will come over from their home country South Africa for a short stay in Amsterdam in the month leading up to the opening on August 28th 2016. During their stay, they will explore the local context and create new, on-site work based on their interactions and experiences. Below they explain their working process.

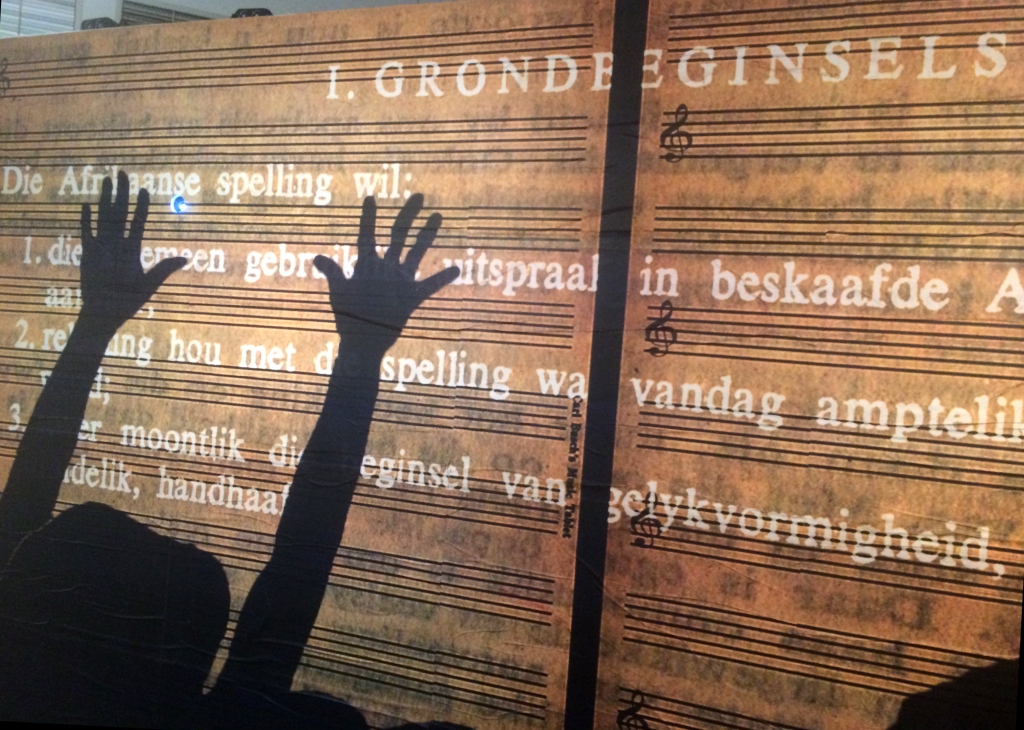

On Straatpraatjies

What would historical transcriptions in the present landscape look like? What kind of story could be told through an intersection of language, music and space? These are questions which we seek to play with through the use of Khoi, Arabic, and Afrikaans. The city architecture is a grammatical structure that we interrupt with our own historical punctuations. We borrow and blend words, placing them in a mengelmoes conversation that speaks to silence and voice both visible and invisible in historical narratives. For us, the creation of Afrikaans and its resilience parallels with Cape Jazz and carnivalesque musical traditions of improvisation and spontaneity. Traditions which are rooted in expression amidst oppression.

– Burning Museum

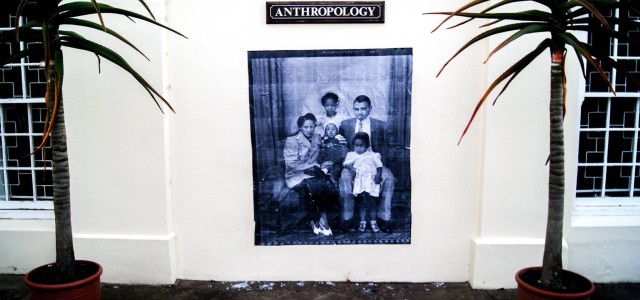

Part of the Burning Museum Collective at a Framer Framed event in 2015. Photo: Marlise Steeman / Framer Framed

“Stop telling us how to eat our own fucking supper”

Ilham Rawoot meets up with Justin Davy and Tazneem Wentzel of Burning Museum Collective

This is the second time Burning Museum is visiting the Netherlands, but the first time they are exhibiting their work. During the collective’s last trip to Germany in 2015, where they interacted with missionary archives, the collective researched the Dutch context in preparation for this exhibition in August 2016. Their eyes less bright than their first visit, they are now coming with experience, and the knowledge of what is most lacking in Dutch society – conversation. The incongruence between the country’s historical colonial destruction of South Africa, and its unhindered practice of patting itself on the back for what it believes was its progressive ideals and support for the anti-apartheid struggle. For the collective, this knowledge was aggravated as the artists found themselves in an artistic space where societal critique is rarely encouraged.

Justin Davy once called the Netherlands home for a while, when he lived there for three years. His time spent within the Dutch cultural arena and his subsequent trips back to the Netherlands, most recently with Burning Museum, have helped him to decipher some of the subtle racism embedded in Dutch society.

It was an interesting return in the summer of 2015, provided with a different lens through which to look at Dutch society – one informed by his experiences back home in South Africa. Now he had the opportunity for critical engagement. For Tazneem Wentzel, in her first visit, she was in awe immediately after disembarking the train in Amsterdam. She relays her thoughts: “The first thing I noticed was how tiny it is. It’s such a small space. When I went there and saw the other side of the story, I thought so much about how the Netherlands managed to become a multinational corporation if it’s a little baby country.” She is deeply puzzled by the lack of questioning by the Dutch public on the origin of their wealth. “The wealth in the Netherlands, where the fuck does that come from?” she asks. The Netherlands doesn’t have any raw materials, they don’t have anything. So where do they get this wealth from?”

There seems to be an avoidance of interrogation of such questions, the collective found. Last year, the collective made a trip to Germany where they interrogated the shared history between Germany and South Africa through the Moravian missionary archives. Here they experienced a lack of trust by the local art establishment in the work that they may create; a fear that they may evoke uncomfortable thoughts and spaces. The collective has gravitated towards each other through the imperative need to integrate their histories into the archives, both South African and European. In Germany, Davy could show people a picture of his great-grandfather, and aunt and an uncle in the archives. “There is a shared history, and it’s not as far from home as the Dutch and German public and art world choose to believe, but rather it’s much more “in your face and a bit too close for comfort.”

With the collective entering the Dutch exhibition space of Framer Framed, as with most of their work, almost every time they have no clue what will come out at the end. But in a situation like this, where they are being funded by a Dutch entity, there will likely be more than one problem that will come up during the process. Wentzel says: “You might piss people off or make people uncomfortable along the way, and that’s the way it is. So what? They may not invite you back but you still have your artistic integrity at the end of the day.”

It has happened in the past, with previous invitations from Europe, where they have been told that they can produce anything on condition that it is not an institutional critique, But if they find the conditions under which they can produce their work problematic, then they merely build that into the work and talk about it.

In the collective’s last visit to the Netherlands, their work on the shared Moravian history mentioned earlier created visible uneasiness, and understanding the reason for it partly influenced their new work. Wentzel says that much of the knowledge in European museum spaces revolves around the idea that the book has immense power, and there is great danger in the reliance on books and theory to provide the belief that the reader is an expert of the subject. In Dresden, for example, Wentzel suspected from her experience that German artists, public and museums have a very specific idea of what an African artist is and should be, based on that ‘power of the book’. The way the collective operated was not in line with what was expected from a group of artists from Africa. It wasn’t distant and exotic.

Often, the interactions they have had in Germany and the Netherlands with regards to art and interpretation of the archives has been patronizing: Wentzels response is: “It’s so fucking arrogant to tell me that you’re sure I’ve read this or that book, like a book on the Cape Malays. No. I eat my mother’s food that’s how I fucking know about my history. I don’t need to read the book. You go read the book. Don’t tell me how to eat my fucking supper.”

For Wentzel, the collective’s first visit to the Netherlands was educational, selfish even. She was there to “see what was going on and to address the headquarters”. It was the collective’s process, and they were just scratching the surface. This time she wants to go deeper. The education about what they learned from their visit happened back home in South Africa, where the response was interesting – people were keen to engage in the idea of working with the archives. They were curious about the idea of navigating the European archives.

In South Africa, there have been unbroken structural barriers to access to the archives for the collective’s parents which, even though they cannot delve into in such a short time, are narratives and people which are important to connect with. What is really important for the collective is to be able to be in control of how they present themselves. Wentzel says, “What I want is for us to position ourselves, and not be positioned by anyone.” While they cannot create a new archive, they see their work as restructuring relationships to the current archive, a relationship that has been violently disconnected. The only reason Wentzel knows anything about her mother’s family is because of the information needed when they made a land claim on District Six following the forced removals in the early 1960’s. “There is a whole story that has disappeared”, she says. “Our people don’t realize that they do actually have a stake in the archive and that it is also their archive. We have roots in this place. There’s obviously a lot of pain and trauma that have been passed on and there has been no effort to connect the dots.” While they will never be able to recreate the full picture, they hope to develop a better idea of what it could look like. “It’s like a pixelated picture but it’s still a picture. It’s saying: You don’t come from nowhere. You’re not a fucking alien.”

Text and interview by Ilham Rawoot

Contested Heritage / Collectives / South Africa /

Exhibitions

Exhibition: Re(as)sisting Narratives in South Africa

Exploring lingering legacies of colonialism between South Africa and the Netherlands through engaging with contemporary artists from both countries