Photo © Stephen Tayo

Photo © Stephen Tayo Stephen Tayo on Capturing the Streets of Lagos

door Rolien Zonneveld

April 2021

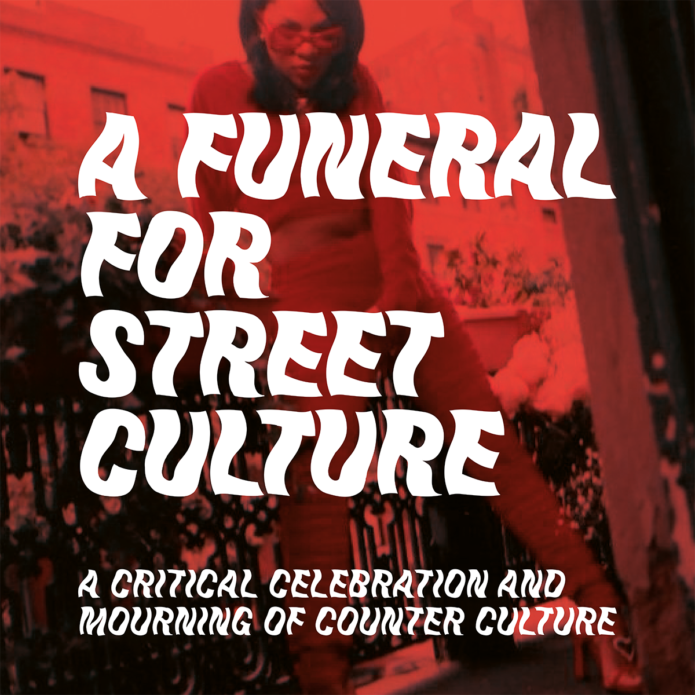

Stephen Tayo is a fashion and documentary photographer based in Lagos, Nigeria. He is one of the contributing artists for the new group show A Funeral for Street Culture – a theme that resonates with his work on multiple levels. For decades the streets of Lagos have proven to be a site of contestation: it is the place where people socialise and flaunt their fashion, but it is also the place where Nigeria’s government exerts excessive power. Here, the photographer reflects on his photojournalism.

© Stephen Tayo

A girl gazes in the camera. She’s sitting on a scooter – her attitude exuding confidence – and she’s wearing a fitted suit made from vivid textiles, topped off with a pair of silver cowboy boots. Behind her a wall sign reads ‘This house is not for sale. Beware of 419.’

We are in Lagos, Nigeria – a hot, bustling urban sprawl counting upwards of 22 million inhabitants. The city’s streets are one of the main hunting grounds for fashion and documentary photographer Stephen Tayo (1994). In the city’s numerous market places, incomplete infrastructures and city squares is where he scouts people with an idiosyncratic style whom he then photographs on the spot. From sporting contemporary streetwear to traditional printed garments, Tayo has a keen eye to flush out interesting characters out of the crowd.

Lagos proves to be an excellent backdrop. It is a city that brims with both creative dynamism and tradition. Paired with the sturdy confidence of its residents, the result is a city where dressing is valued as highly as any major fashion capital, if not more so. “I love fashion, but not necessarily the staged and forced photography that comes with it. I prefer to capture it the way one encounters it in one’s daily life,” Tayo explains in the run-up to the exhibition. His Instagram page, which has already amassed more than 40,000 followers, therefore feels like a visual diary. “I shoot what I encounter in Lagos and I am grateful for the recognition I receive through the platform. The infrastructure for creatives in Nigeria is limited – you have to do it all by yourself. Instagram has enabled me to work with creatives outside of Nigeria and build up a network.”

© Stephen Tayo

Contrary to what you might expect, the photographer has had no formal training and is self-taught. Having graduated in philosophy at university, he started out as an assistant, and then started styling and photographing himself. The equipment he started off with consisted of nothing more than his iPhone. “In the beginning I didn’t have a professional camera due to lack of funds, but I didn’t want it to limit me,” he says. “Later I realised that the camera is not the most important element of your practice. Your eye, your dedication and your experience – that’s what it’s all about.”

On the streets is where Tayo feels most inspired. “The way Nigerians carry themselves when they leave the house is truly unique,” he explains. “Even if it’s just going to a restaurant, they will make an effort.” While the pandemic did not spare Nigeria either, Tayo explains it hasn’t impacted the way people present themselves, even if there are barely any events to attend. “You can see people colour coordinating their face masks with their outfits as if it’s the latest accessory.”

Additionally to documenting street style, Tayo has also become known for capturing the city’s creative community and burgeoning subcultures; from gothics to fashion designers, and from models and musicians, to drag queens – Tayo has captured them all. Dressing unapologetically – and that includes having tattoos and wearing expressive makeup and accessories – isn’t something generally accepted by society.

In the 80s, the country was going through a series of military juntas in which cultural and artistic expression were suppressed and heavily policed. Consequently, the regime began censoring mediums that were considered ‘defiant’ – such as music videos. Since then, the government has returned to a democracy, but most of Nigeria remains politically, socially and religiously conservative.

© Stephen Tayo

The Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act that passed in January 2014 is one of the many examples revealing this deeply entrenched conservatism. This act not only criminalises marriages and civil unions of same-sex couples, it also bans public gatherings perceived to be in support of Nigeria’s queer community, including art exhibitions and performances.

The act has bred a volatile vigilante culture, in which the police have started to treat people in any way that they please. According to accounts gathered by Human Rights Watch, the police torture and force people to confess, and when they hear about a gathering of men, they can make arbitrary arrests. Additionally, there have been rising incidents of mob violence, with groups of people gathering together to commit acts of violence against persons based on their real or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. Dressing in what people perceive to be a “gay” fashion – wearing nail polish or extravagant clothes for example – can make one incredibly vulnerable to violence.

One of the communities impacted by this act has caught Tayo’s eye: the city’s drag queens. While they have been gaining mainstream attention over the last couple of years, the Same Sex Act has made it incredibly challenging to physically share their artistry with the public. Forced out of physical spaces, the drag queens have to take their work online – using social media platforms like TikTok, Instagram and Snapchat.

Call Me Boogie (2020) © Stephen Tayo

One of the portraits from his drag queen series What If (2020) is part of A Funeral for Street Culture. In the photograph we see the young drag queen Boogie wearing a hat with fringes hanging from the brim, obscuring her face. While it gives the photography an air of mysticism, it is unfortunately a necessity to protect the performer’s identity. In the current climate, both the drag queens and the photographer documenting them face police harassment.

In October 2020, the youth of Lagos took their grievances to the street in what grew to be the largest popular resistance against the government in years. The demonstrations began as an outcry against a notorious police unit known for their widespread abuse, but evolved into a larger protest over bad governance. Out of a sudden Tayo found himself in the midst of it, capturing the protests live on Instagram with his iPhone. From shooting street style, he had now become some sort of war photographer, exposing the severity of the protests to his worldwide audience. “While it was a traumatising time, it also made us youth feel empowered,” he explains. “It felt good to join this movement and advocate for real change.”

The streets thus contain multiple meanings for the photographer; on the one hand they act as a stage or runway, where people can come together, flaunt their outfits and celebrate, while on the other hand it is a heavily politicised space where some of the most marginalised communities cannot move freely. According to Tayo, that’s one of the reasons he will continue working on documenting these subcultures and communities – to give them the voice and support they need.

Photography / Queer /

Exhibitions

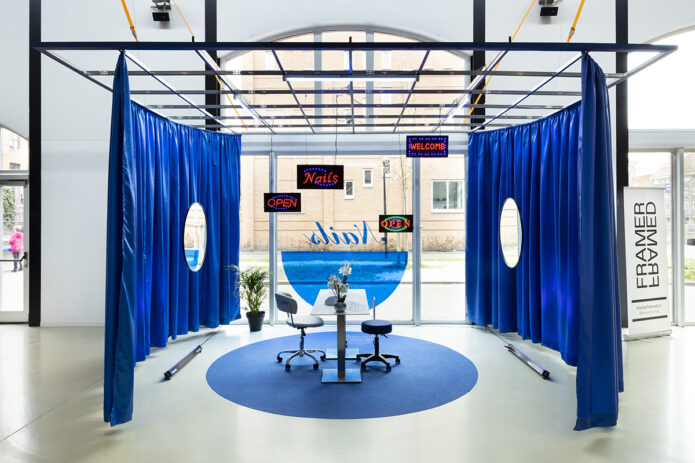

Project: A Funeral for Street Culture

A group project by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo hosted by Framer Framed

Network