From the series 'Gifted Mold' © Cédric Kouamé

From the series 'Gifted Mold' © Cédric Kouamé Cédric Kouamé celebrates the beauty of damage

by Rolien Zonneveld

June 2021

Ivorian artist Cédric Kouamé is a jack of all trades: he sculpts, he collects, he photographs, he makes music, he DJ’s – the list goes on. A common thread to his multidisciplinary practice is a ferocious curiosity that drives him to constantly explore and to forge unique collaborations. Take ‘The Gifted Mold Archive’ for example, an ongoing project in which he unearths moldy family photos and repurposes them into new works of art.

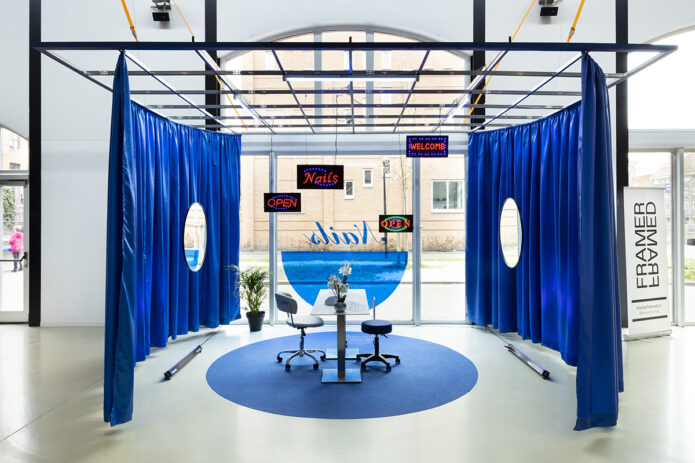

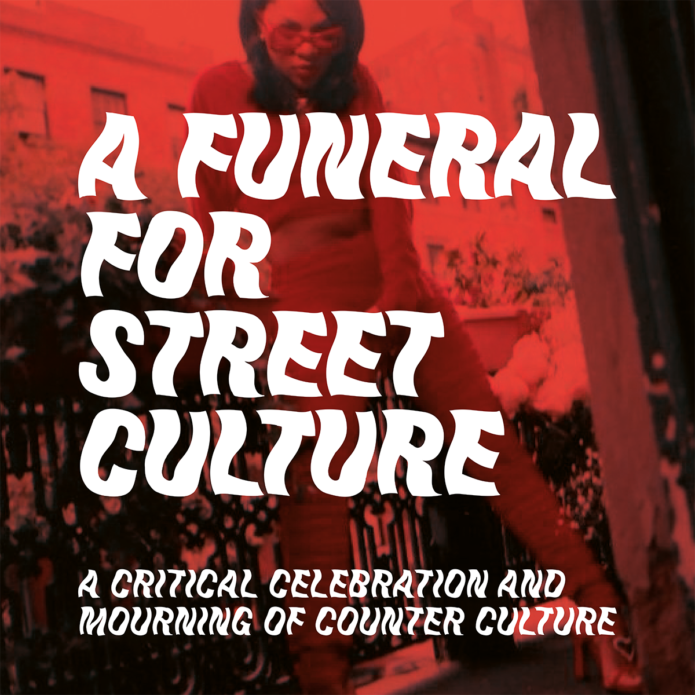

Kouamé is one of the participating artists of the current project A Funeral for Street Culture, where his video work All together, until then is on display. Here, we shine light on his passion for archiving and collecting objects, and why there’s an artistic quality to decay.

Cédric Kouamé has a compulsion to collect – he simply can’t help himself. Whether it’s digging through second hand books, sifting through piles at thrift stores or gathering records, tapes, zines, crystals and stones, he sorts and keeps anything and everything.

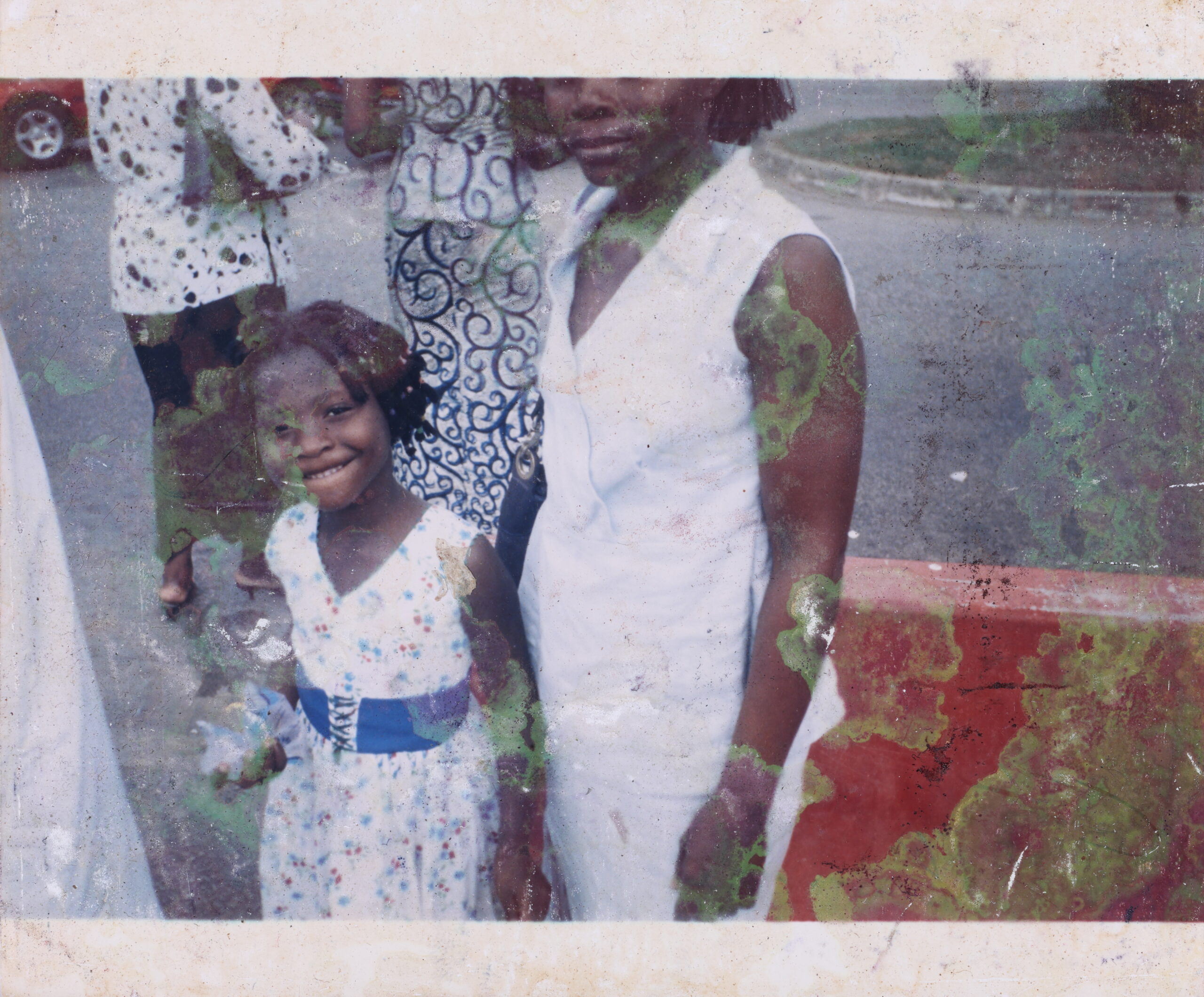

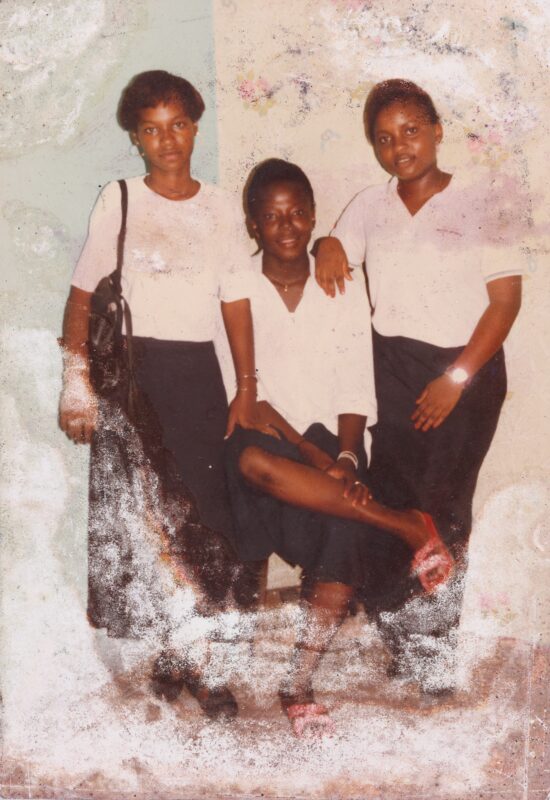

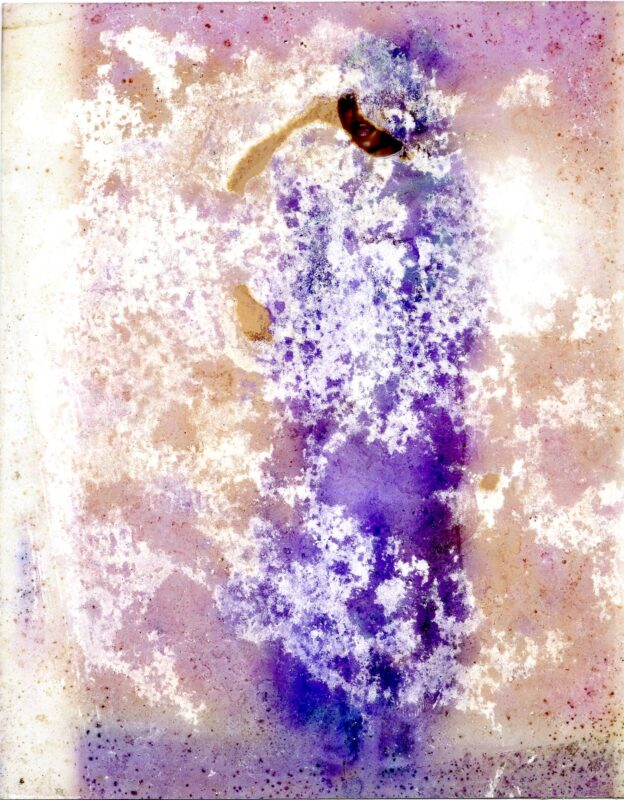

In 2012 this tendency started to coincide with a new-found love for analogue photography. But not just any photography – Kouamé grew particularly fond of those posed studio portraits that can be found in numerous photo albums across the globe but which have a particularly strong tradition in West-Africa. With excitement sparked, he decided to revisit some of his own family albums, as his family had always documented themselves quite extensively. While doing so he soon realised that a large portion of the images had become moldy. Studying the decay with the eyes of a microbiologist (“My father is one, I think I got it from him!”) Koumé concluded that there was in fact a beauty to the process of degradation, giving the photographs an entirely unique aesthetic.

From the series “Gifted Mold Archive” © Cédric Kouamé

Soon he made a discovery that would birth an entirely new obsession: not only had his family photos been affected by the mold, it actually was a very common occurrence in the region due to its damp climate. Multiple photographs he came across were affected in very similar ways: the colourful dyes of the ink had bled into the photograph, like bacteria cultures with ruffled edges and a stunning pastel colour palette. As a result, the images had become striking works on their own, assuming an almost artistic quality.

If Kouamé wanted to get his hands on more, he needed to start reaching out to the few photo studios Abidjan harboured, where photos were still being developed. And so he did.

From the series “Gifted Mold” © Cédric Kouamé

The first set of photos he got he hands on would turn out to be an expansive collection he found in the trash can of a photo lab located in Ajdame, a place where he grew very attached to. “I’m still going there from time to time to buy films and have conversations with the people there,” Kouamé explains. “At that time I only wanted to collect photos and to build a solid archive but then I met Kefana Soro, an Ivorian sculptor.” He offered to donate Kouamé a selection of his own family archive for his project. “Me and Kefana then worked on locating the origins of each picture. We were successful in doing so for some of the photographers and locations. It really started to feel like a crossover between archeology and anthropology.”

It is quite an accurate comparison: Kouamé is in fact somewhat of a modern day anthropologist – someone who tries to understand contemporary cultures by studying its visual garbage. By sorting images along certain themes, for example wedding processions, the project says something about the social environment of Cote d’Ivoire – revealing details about the sartorial choices of the time, and offering a glimpse into family histories.

From the series “Gifted Mold” © Cédric Kouamé

“These photographs are part of our country’s heritage. They are visual proof of all the micro histories that Cote d’Ivoire is made up of,” Kouamé explains. “If these images perish as a result from the mold, the stories go along with them. I am a firm believer that there is a drastic need to collect them, and as such, preserve the many untold stories. One of my long term life goals would be to build a center for preservation of photographic archives in Abidjan.”

There are certain art critics who believe that found photography is not art because the artist who found the photo did not embed any meaning or spirit into it. Judging by Koumé’s project, we couldn’t disagree more. What makes found photography so special is that it blurs the lines between art and document, and at times between collector and artist. By using other people’s photographs, Koumé has created a body of work that is both alluring and captivating. Luckily for us, the collection is ever expanding.

From the series “Gifted Mold” © Cédric Kouamé

A Funeral for Street Culture is an ongoing project by Metro54 and curator Rita Ouédraogo, which can be visited at Framer Framed till August 8, 2021. Koumé’s selected video work on display is a result of a workshop he did with Ivorian sculptor Kafana Soro, in which he learned how to carve wood with the local tools. After spending working approximately two month on that piece, Koumé decided to burn it in order to protect the wood piece from bugs and insect. The video is showing the process of burning the sculpture.

Photography / The living archive /

Exhibitions

Project: A Funeral for Street Culture

A group project by Metro54 and Rita Ouédraogo hosted by Framer Framed

Network