Exhibition: A Dream of Africa, Images of a Continent at the 'Golden Age' of Colonisation 1920-1940. Museum of Fine Arts, Tournai

Exhibition: A Dream of Africa, Images of a Continent at the 'Golden Age' of Colonisation 1920-1940. Museum of Fine Arts, Tournai Exhibition: A Dream of Africa, Images of a Continent at the 'Golden Age' of Colonisation 1920-1940

Africa in the Limelight

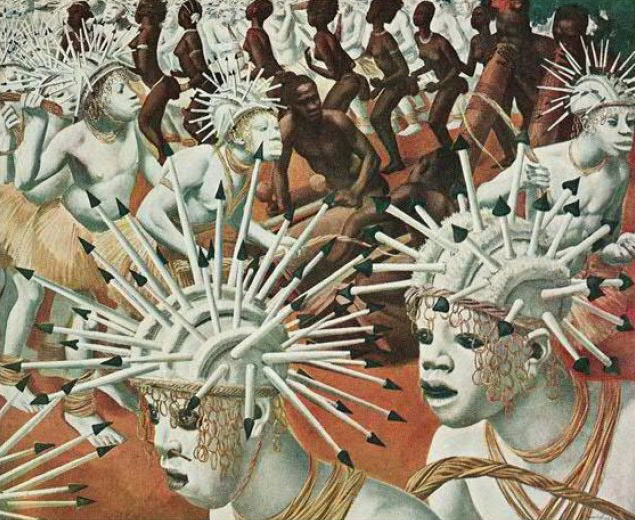

In this year of commemoration of the major African independences, and especially that of the Congo, the former Belgian colony, it has deemed appropriate to illustrate how this particular country, but also in the broad sense Central and tropical Africa around it, inspired the vision of Western travelling artists (painters, sculptors, photographers) who went over these territories to explore their landscapes and marvel at their peoples at a key moment in their history (the 1920s and 1930s), often described as the ‘golden age’ of colonisation.

The Africanists’ Dream of Africa, or a transfigured reality

In the aftermath of the deep moral trauma generated by the First World War in the West the 1920-1930 decade – better known by its generic name of “Roaring Twenties” – experienced an unprecedented ‘vertigo’ for Black Africa. It perceived Black Africa as the ultimate refuge of authenticity, purity, innocence and dream against the “ruthless world” of Europe, which had been devastated by destructions and bloodshed, but also increasingly more disfigured by industrialization and rampant materialism.

Such general need for healing and “humanism” became the prompting force of “primitivism” in all its aspects. It partly explains the calling of many idealists, artists, writers and intellectuals, who travelled to tropical and Central African colonies in search of more “profoundly alluring” and attractive places than their own distorted environment. They thus walked in the footsteps of their illustrious predecessor and somehow spiritual father Paul Gauguin. Individual experiences of Belgians August Mambour and Pierre de Vaucleroy, or the French Fernand Lantoine, André Gide and Marc Allégret are essentially derived from this trend.

Beyond this sentimental or philosophical aspect, the inter-war years also correspond historically to the largest expansion of the African colonial enterprise copiously promoted by “propaganda” – or what would nowadays be rather more delicately phrased “propagated or enhanced” through image and setting. At that time there thus proliferated, particularly in Europe, sprawling world or colonial exhibitions. The ones in Antwerp in 1930 and Paris-Vincennes in 1931 were culminating points, with successive contributions by two Tournai-born artists, painter Allard l’Olivier and architect Henri Lacoste.

The official promotion of colonies went alongside with renewed particular attention for ethnographical and geographical issues, as they met the objectives of better understanding and acceptance, or integration of the territories and the populations under the tutelage of the mother country. The extensive photographic collection methodically assembled by Polish photographer Casimir Zagourski from the 1920s on fits perfectly in this context, as does the celebrated Citroen expedition called Black Cruise which drove across Africa in half-track vehicles and brought back an exceptional harvest of painted (Alexandre Lacovleff), filmed or photographed (Léon Poirier) images.

Finally, in the strictly aesthetic field, the various issues related to “primitivism” confirmed the leading role that the black continent was to play in arts debates. Their main stake became “wringing the neck” to a style – Art Nouveau – and to a school of art – Impressionism – henceforth looked upon as decadent and ill-adapted to the emerging new world of hyperactivity, violence and mechanization. The advent of both Cubism and Expressionism became its most striking manifestation. A more or less marked echo of these avant-garde trends is found in the inter-war years Africanist production, although they rather took on the form of an aesthetic compromise: “Art Deco”, which is largely derived from negro art through its intense rhythm and its insistence on stylisation. The cultural influence of Africa would also extend to other aspects of creation, like such forerunners of our era as music (jazz) or fashion.

This refreshing wind also accounts for the discovery and then the concomitant revelation of a series of Congolese craftsmen (with Lubaki and Djilatendo ranking among the bestknown). Their themes and decoration, both naïve and humorous were often tinged with hints at the colonial presence and turned them into so many African “Douanier Rousseau”.

The vast majority of Africanist representations from that time reflect the deep admiration and empathy felt by Western artists for the natural or individual models they encountered throughout their ceaseless wanderings. Some of them also illustrate certain prejudices or fantasies which then prevailed in the Western world around the notion of barbarism or savagery, or even in the field of eroticism; other images, however, even explicitly denounce given aspects of colonization.

The exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts (Tournai) sets out to highlight the many political, cultural, philosophical or aesthetic factors at work to originate the Africanist “trend” and output. An extensive journey through different sections and the some two hundred gathered items will cover the many aspects of painting, sculpture (with Dupagne and Matton), architecture (with original projects by Lacoste), film, photography and even literature.

Museum of Fine Arts (Tournai)Colonial history /