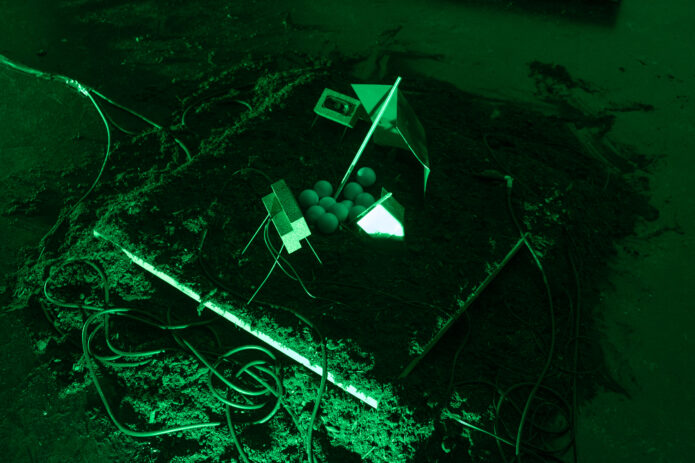

'Respiration' (2021), by Jun Zhang. Courtesy of the artist.

'Respiration' (2021), by Jun Zhang. Courtesy of the artist. Five art graduates on how climate justice and ecology inspires their practice

by Ella Fengler

December 2021

Since the opening of the first Framer Framed exhibition in 2013, art has been conceived as an agent for social change. It’s ability to act as an agent of change has been central in our curatorial approach.

“Artists have the power to make other worlds palpable, imaginable and visible,” Jonas Staal explained earlier this year, in light of the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC) – the project that has taken over the main space over the last months. When we speak about imagining solutions and new perspectives on the climate crisis, we cannot leave out artist.

A new generation, freshly out of art school, is ready to take on the climate crisis. It’s a generation directly affected by climate change. It’s about their future, the planet on which they and many following generations will live. To spotlight some of these voices and fresh perspectives, we have approached a selection of 2021 art graduates, Joel Heikkinen, Lance Laoyan, Milah van Zuilen, Valentine Langeard and Jun Zhang, whose practice centres around themes of climate justice and ecology.

How do these students use their art to express discontent, offer insights and propose new ways of cohabitation? Are they optimistic about the future? And what role does art play in future solutions? The fresh graduates come from various Dutch art schools and different courses, ranging from Photography to Studio for Immediate Spaces.

Joel Heikkinen

Photography at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague

Joel Heikkinen, Heijastus (2021). Courtesy of the artist

What was the inspiration behind your graduation work?

My work is about reflecting on changes happening in life and the various emotional responses to these changes. A very prominent change in my life, coming from a Nordic country, is the disappearing of the winter landscape. Growing up, I took it for granted that snow would cover the ground every winter, yet already during my short-lived life, the world and the climate have undergone a drastic change.

Could you introduce your graduation project?

In Heijastus, I tell the story of a winter day which only exists within my dreams. In a specific dream, I saw myself playing in the snowy landscapes of my childhood with family and friends. The warm and precious image was a big contrast with the grey snowless world that was outside when I looked out the window. It brought sadness over me, it seemed like my mind was subconsciously mourning. For Heijastus I researched this complex feeling of an identity that is fading caused by the climate crisis.

Why did you choose medium photography and what role can the medium play in the climate crisis?

The project was presented in an installation that combined photography, writing and music. It very much feels like a diary. I like to consider my photographs as paintings rather than documents of what was in front of the lens. My approach to photography is that it’s a continuation of my thoughts, it allows me to hold on to moments and memories that would otherwise be fleeting. By sharing these personal stories that relate to a larger extent I can remind people of the beauty of nature as well as the effect the climate crisis has on our daily lives. People are often led by their emotions so I think that this could be an interesting way of approaching the topic of the climate crisis. Intimate and approachable material is easier to process than all the scientific data and graphs we encounter on the subject. Furthermore, photography can serve as clear evidence on the impact humans have had on the planet. Documentation of the changing world can operate as warning signs. For example, images of the wildfires in the boreal forest zone of Canada, where the climate is fairly similar to that of Finland, warn me of what could also happen here.

Lance Laoyan

Non-Linear Narrative at Royal Academy of Art, The Hague

Lance Laoyan, Our Shared Acoustic World, installation (2021). Courtesy of the artist

Could you tell us about your graduation project?

Our Shared Acoustic World came from my research on how we can better use our ears as tools to engage with nature. The thesis pulls the reader into the sonic world and provides different ways to think through and understand their surrounding environments. It poses questions about sonic justice and agency. The resulting audio-installation highlights the complications that surround acoustic territories of machinery and nature. Focussing on anthropogenic noise from highways and industrial facilities that impacts the biology and environments of frog species such as the Tungara and Knoflookpad. The project is inspired by indigenous ways of listening and their non-verbal communication with their surroundings. The audience listens to soundscapes I composed from my field recordings and a spoken narrative forcing an immersive sonic interaction with my audio piece. It’s the competition between being heard and being silenced.

What shocked you in your research about noise pollution and how did you mould the research into a storyline?

Whilst I was field recording in Delft, I was appreciating the singing and chirps of local birds. As I listened there was a slow crossover from when a truck or large vehicle was parking with a loud engine. The birds fell more silent every minute as the vehicle kept rumbling, some flew away and some just stayed silent. Witnessing this was profound and it was an essential moment that pushed me further in my research. The general storyline in my installation encompasses my research which I undertook through listening sessions and recordings in the field, interviews with multiple ecologists and architects and reading through scientific papers on the matter. From all of this data, I analysed what I found important and wrote a semi-fictional story of a hopelessly romantic frog that wants to woo a female with his singing, but along the way to doing so, he encounters multiple anthropogenic obstacles that degrade his abilities.

What do you as an artist wish to contribute to the discussion and solution-seeking of the climate crisis?

As Western society predominantly lives through visual perspectives, I want to bring more attention to our ears; to investigate ways in which we can communicate other meaningful experiences. For me, Pauline Oliveros’ Deep Listening practises shifted my perspective on the world. It is a way to connect with the physical environment by building a relationship with nature through paying attention to the nuances of sound. I feel that we are slowly losing connection with nature, we are distinguishing ourselves from it. In order to take action in the climate crisis, we need to fundamentally re-connect ourselves with the earth.

Milah van Zuilen

Photography at Willem de Kooning Academy, Rotterdam

Milah van Zuilen, Mom’s Walk, Český les, detail 2 (2021). Courtesy of the artist

Could you tell us about your graduation project?

My project, Terrafuturism, investigates a different approach to ecological fieldwork. The making of the series followed a fixed structure: during a systematic walk through a specific area leaves were collected, afterwards dried, then cut into squares and neatly arranged in a grid. In doing so, I act as a forest ecologist, gathering and ordering material to understand and oversee nature. Grid structures are often used to impose an anthropocentric order on the landscape, in cartography and taxonomy but they also appear physically in landscapes. I want to evoke questions about this human urge to structure and create ownership over land.

How do you as a maker fluctuate between rationality and intuition, science and art?

Even though the work is made in a very structured manner at the same time it was a meditative experience. The methodology is about closing observing details, differentiating the landscape from a closer perspective. Because the new whole of leaves show the material as it is, the complex beauty of the leaves is still visible in the contrasting organised grids.

What do you as an artist wish to contribute to the discussion and solution-seeking of the climate crisis?

I would like to continue to bend art and ecology closer together. Working interdisciplinarily allows me to question my skills and knowledge from multiple perspectives. My goal is for the viewer to find (new) appreciation for nature in the form she already has. Which can lead to a nicer attitude towards the environment. Artistic imagination offers hope and re-appreciation. The world of environmental scientists is very inspirational, but the harsh reality of climate change can be incredibly confronting and concerning in this setting. The field of art seems needed to provide helpful solutions. In so many ways the climate crisis is too complex and big to grasp and art can help people to see the mess we’re in, to then try to reimagine and transform it.

Valentine Langeard

Studio for Immediate Spaces at Sandberg Instituut, Amsterdam

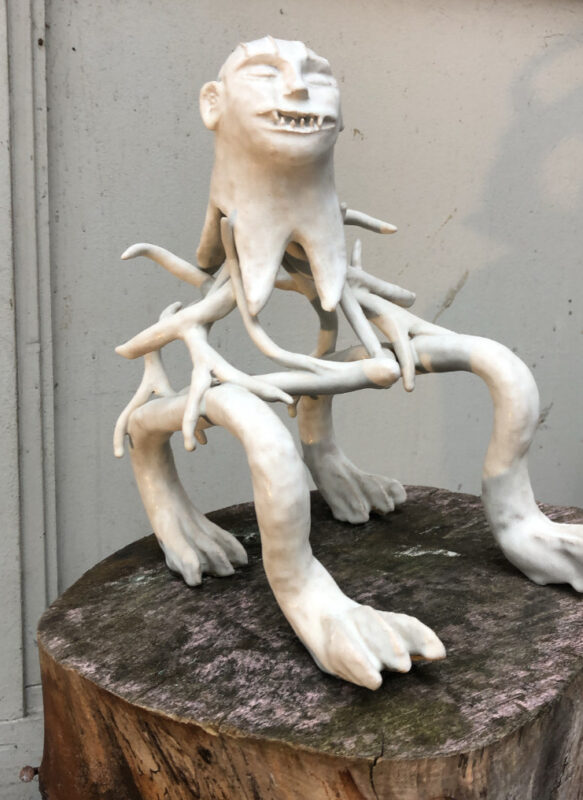

Valentine Langeard, Furtives (2021). Courtesy of the artist

Could you tell us about your graduation project?

I made two parallel projects revolving around furtives. Furtives are a fictional species from a novel by writer Alain Damasio, which don’t have a fixed shape but are in perpetual metamorphosis to unite with their environment. I visualised the furtives under two shapes, as moving sprawling plants and as frozen statues.

They can’t stop the spring, is an installation occupying an abandoned garden in the middle of Amsterdam to protect it from future destruction. The garden is guarded by a furtive, the sculpture functions as a scarecrow for anyone that wants to harm the ecosystem. It embodies the spirit of environmentalists. The video We shine among fallen leaves is a 3D modelling of De Kaskantine, an urban farm. It starts from a real reproduction of the urban farm and evolves to a fictional and speculative landscape. De Kaskantine is a place where citizens can live in harmony with nature and transformation. In the immersive 3D-video, I visualise their view on living together.

What do you as an artist wish to contribute to the discussion and solution-seeking of the climate crisis?

As an artist I feel the need to support ecological fights, during demonstrations you might spot me performing on my stilts to attract attention. My projects are always focussed on ecological issues. Artists should make use of the space they have to freely express their political views. Artistic practice is close to journalism, as artists also serve the purpose of informing people, but without having to stay within certain rational frameworks. I collaborate with environmental activists to make their demands and dreams which I share visible. With symbolism and fantasy I can draw attention to ecology in a different way. Collaboration outside of the art field is very important, it offers ways to concretely help communities and encounter a broader public. And in my opinion, art makes an impact when it’s outside of the museum.

Jun Zhang

Studio for Immediate Spaces at Sandberg Instituut, Amsterdam

Jun Zhang, Respiration (2021). Courtesy of the artist

Could you introduce your graduation project?

I based my graduation projects on research into the Dutch shell lime industry. Both projects are set in a post-Anthropocene scenario. The installation Speculation for a drifting garden presents a speculative biodiversity hotspot. Where, in the decolonisation of nature, different species live harmoniously and new ones are born. Respiration is an interactive installation that invites the viewer to become the medium. The human breath, which consists of carbon dioxide, finds its way through a tube to living creatures made of shell lime skin. This strengthens the skin and the humidity and microorganisms will activate the cells inside, a new life form is born. The speculation is rooted in these ideas: could the carbon dioxide emissions that caused global warming and climate change become the basis for the birth of new species? And could the bacteria that caused human deaths become an opportunity to breed this new species?

What does your portrayal of a post-Anthropocene scenario bring to the present?

Speculation for a drifting garden aims to reconnect humans with the planet. The speculative scenario combines technologies accumulated by civilisation over the past millennia with climate and environmental changes and non-human species. It is a man-made garden of shell lime rockeries. Shell lime symbolises an excellent human technique, shell lime plaster and its production had a deep influence on the urban and natural environment of The Netherlands. The human possession gradually returns to the nature it was taken from, as the garden becomes flooded due to the sea level rising and the shell lime rockeries become the shelter for sea animals. With this scenario, I try to demonstrate the possibility and speculation of nature no longer being the mining ground for human resources, but a biosphere also including humans. The climate and environment of our planet could work together with human knowledge and techniques to weave new species and ecosystems. My artistic research and immersive constructions can be seen as poetic and imaginative worlds complementing the scientific and rational world model.

Are you optimistic about the future?

It might seem as if I’m more pessimistic, because I imagine a future in which humans may not exist anymore. But on the contrary, I think I’m more optimistic. Even though humans are extinct in my works, they participate in the weaving of the earth’s ecosystems by offering foundations for other species. A future including the extinction of humans could be seen as the result of the reconnection of humans and the planet. To me, that’s a positive future.

Radha D’Souza speaking at the Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (2021). Foto: © Ruben Hamelink

Court for Intergenerational Climate Crimes (CICC) is a collaboration between Indian academic, writer, lawyer and activist Radha D’Souza and Dutch artist Jonas Staal, commissioned and developed by Framer Framed. The project consists of a large-scale installation in the form of a tribunal that prosecutes intergenerational climate crimes.

Ecology / Planetary Poetics /