Exhibition Review: Carnival of Ghostly Delights - by Will Owen

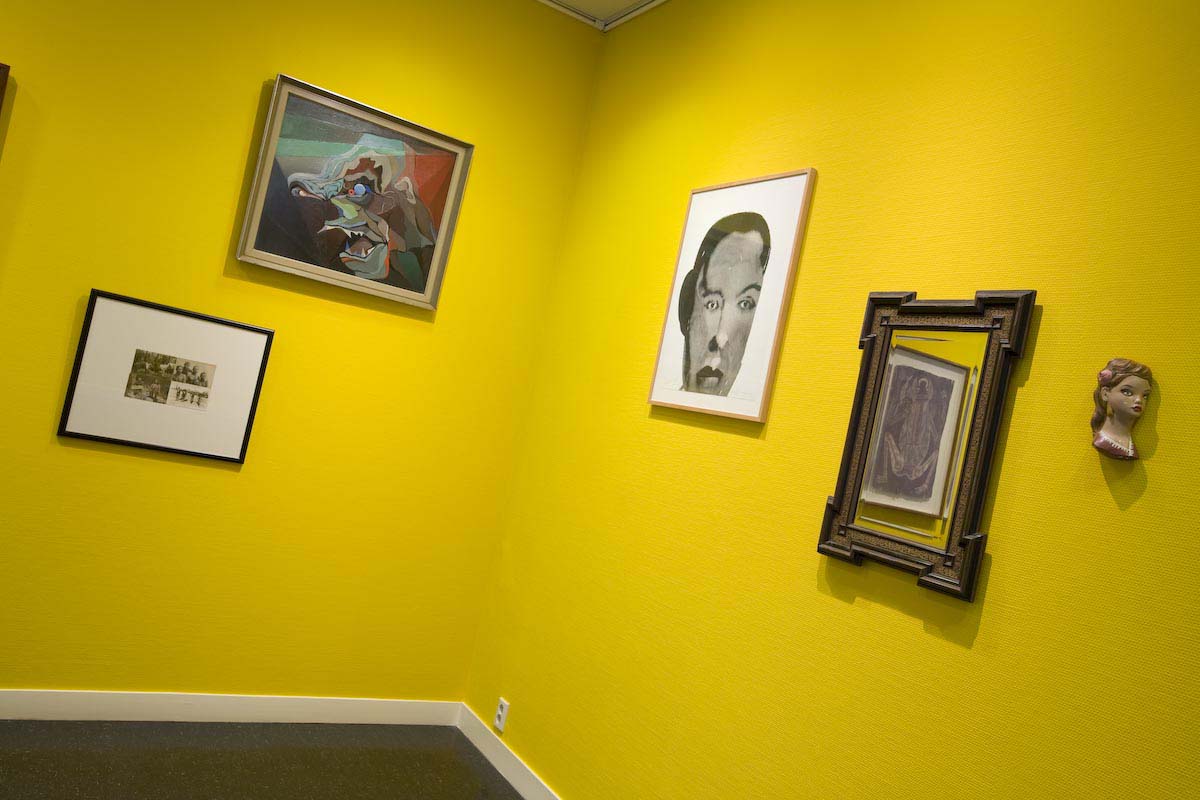

Late in 2008, at the invitation of curator Georges Petitjean, Melbourne-based Wiradjuri artist Brook Andrew turned the entire exhibition space of the AAMU, Museum of Contemporary Aboriginal Art in Utrecht into an installation he called Theme Park. In what he described as the opposite of a solo exhibition in a museum, Andrew turned the museum itself into a multi-leveled exhibition object. If there were ever an attempt by an Indigenous artist to create a Gesamtkunstwerk, Theme Park may well be it. It included original works by Andrew, including his large-scale series of mixed-media canvases, The Island, based on 19th-century drawings of Australian exotica, gigantic inflatable clowns inscribed with Andrew’s characteristic op-art designs derived from Aboriginal dendroglyphs, “found video” of the removal of such inscribed trees by officials of the South Australian Museum, Aussiebilly (“14 rockin’ tracks from Down Under”) and Olivia Newton-John, video interviews with victims of contemporary political “disappearances,” ethnographic artifacts from international museum collections, and Andrews’ own collection of kitsch Aboriginalia.

Hard to imagine? Indeed. And that it why the superb exhibition catalog produced by Petitjean and the AAMU is such a welcome addition to my bookshelves. Theme Park (the book) features extensive photographic documentation of the installation and reproductions of many of the works that occupied the space in Utrecht. There are excellent essays by Petitjean, Marcia Langton, Nicholas Thomas, and Andrew Gardner that address not only the installation itself, but other aspects of Andrew’s long career that shed light on his goals in mounting this extravaganza. There is a photo essay, “Corridors and Boxes,” by Andrew that looks into the incarceration of Aboriginal history in museums, and an interview with the artist by Maria Hlavajova. The handsome hardcover edition even includes a set of three slightly kitschy ribbon bookmarks in the Aboriginal colors of red, yellow, and black.

Brook Andrew, Theme Park (2008), AAMU – Museum voor hedendaagse Aboriginal kunst Utrecht

Andrew’s most famous work to date is probably Sexy and Dangerous (1996), a two-meter tall transformation of a 19th-century photograph of a young Aboriginal man, painted and decorated with headband and nosebone, and further overlaid with three Chinese characters and the English words of the work’s title. Like much of Andrew’s work, it features a collision of ancient and modern, an man whose ritual status is defined by his ornament and denied by his anonymity. Andrew’s work is a portrait of an outsider’s view of the Indigenous; the original photograph was as much a transformation of its subject as Andrew’s late 20th-century manipulation of the image is a transformation of that earlier artifact. The Chinese characters place Australia in an Asian context, removing it from the Antipodean place in nature implied by the original. It asks what sort of reality inheres in the individual and what inheres in the apprehending gaze.

The apprehending gaze, be it of explorer, colonist, or museum curator is Andrew’s perennial subject. And nowhere does it receive a more thorough exposure than in the corridors and display cases of Theme Park. The supposedly scientific documentation of Aboriginal ceremony that forms the core of The Island‘s imagery jostles up against souvenir postcard books of modern Indigenous people. A pair of china plates depicting the characters of Marbuck and Jedda from the famous 1955 motion picture by Charles Chauvel is a tumble down a rabbit hole of images of images of stereotypes of Australian blacks. There are mission-era bark paintings and recordings by Aboriginal country singer Jimmy Little: culture or more kitsch? As with a real life theme park full of roller coasters and sideshows, shock and laughter are the sought-after, simultaneous responses Andrew elicits from his audiences.

Much of the laughter derives from Andrew’s inherent appreciation of the follies of kitsch; a serious man, he has a generous sense of humor, and can spot the ludicrous in the shameful. He makes us smile at the tasteless of ceramic ashtrays, or injudicious contest advertisement that asks the reader to supply a caption for a picture of a young black girl in polka-dot bows and bare breasts offering Violet Crumble to a pack of helmeted soldiers.

When I looked up Violet Crumble (a chocolate honeycomb candy, if you’re not Australian) in Wikipedia, I learned that its slogan is “It’s the way it shatters that matters.” Andrew must have had this doggerel in mind when he selected the advertisement for his Theme Park, as with it comes the darker side of laughter, the shock at the shattering subjugation of Indigenous experience to colonialism, the outrage at the reduction of Indigenous people to stereotypes and, worse, the denial of individuality and humanity, the fracture of culture and lives.

Andrew has done extensive research in the archives of the Mitchell Library in Sydney, where he has uncovered hundreds of photographs of Aboriginal people, like those that feature in his 2007 series Gun-metal Grey, people who have vanished without a trace other than these neglected portraits. This sense of loss and disappearance has led Andrew to an engagement with other forms of disappearance, most notably the victims of political repression and violence at the hands of juntas in modern South America. Relatives of those desaparecidos are among the people who feature in Andrew’s 2006 video piece Interviews, which was included in Theme Park.

In addition to his researches in Australian archives and jumble-sale stalls, Andrew has raided the collections of a dozen museums in the Netherlands, Belgium and France for material to include in his exhibition. This international assemblage of the fruits of colonialism is one of the things that distinguishes Theme Park (and the catalog’s essays) from more conventional examinations of the impact of European expansionism on the Indigenous people of Australia. The theme of colonialism in Indigenous art is often looked at from the perspective of the presence of the English in Australia or the South Seas, perhaps best exemplified recently in the works of Daniel Boyd. What Andrew has achieved inTheme Park is a broadening of scope: he looks for the evidence of appropriation and exoticism (with its attendant dehumanization) worldwide, and folds it all into his own nightmarish Luna Park. The gaping maw that swallows visitors on Sydney’s North Shore has been recast into a voracious global consumer of peoples and cultures. While the Indigenous experience in Australia is still the focal point and the primary means of expression for Andrew, he has managed to cast the local experience as but a single instance of an intercontinental phenomenon whose power extends through centuries.

In doing so, whether intentionally or not, Andrew has positioned himself amongst an international cadre of artists working to define dislocation and disaster, as Andrew Gardner notes, including the American dissector of slavery Kara Walker and apartheid’s inspector William Kentridge. Like many of his fellow art-school trained Indigenous artists, Andrew mines Aboriginal identity for his work; like very few, he succeeds on an international stage where the implications of his Aboriginal identity resonate in new and stronger ways.

Text by Will Owen

Originally published on January 17, 2010 at Aboriginal Art & Culture: an American eye

under Creative Commence license NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0

Contemporary Aboriginal art /

Network

Brook Andrew

artist